I

You’ve done all that research on livestock herders. You’ve collected so much information to better government policy and management. You know all the critiques of big-D development. But no one is acting on your findings and insights.

What do you do now and instead, whoever is listening or not? One answer: try curating publics as a part of your work.

I am suggesting that pastoralist practices–really-existing practices–can be curated so as to create new publics or, better yet, counter-publics. Success is defined as illustrating them, singly and together, in ways that stick in the minds of these publics, regardless of the dominant development narratives already there.

II

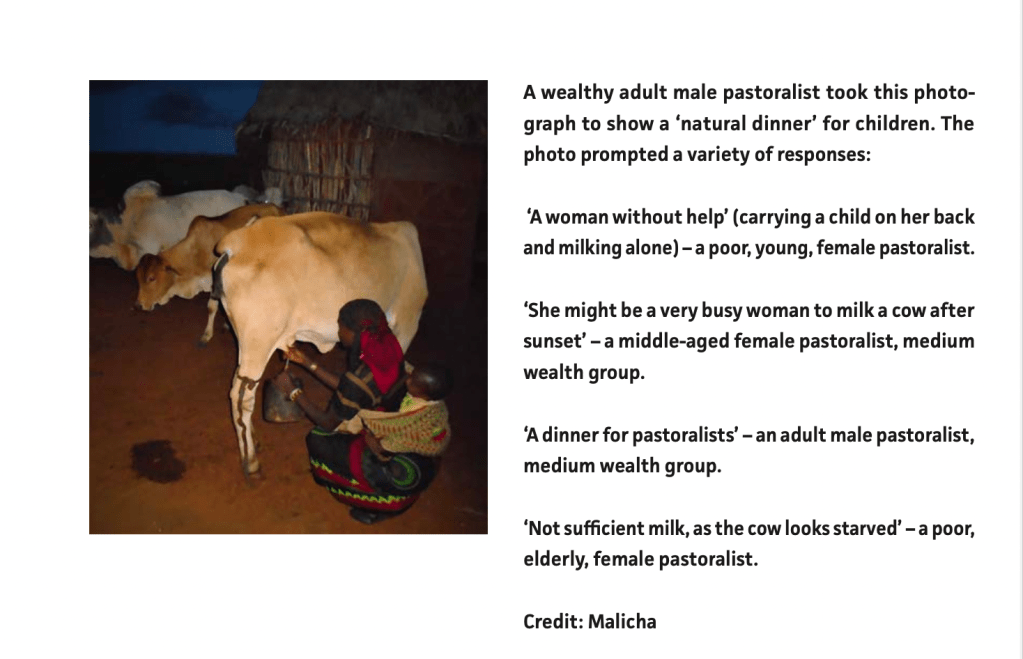

For example, enter the first of several rooms in our exhibition, “Rethinking Pastoralism Today.” On the wall there, you find pictured with a sidebar and attribution:

Source: S. Bose (2023). Photovoice With Pastoralists: A Practical Guidebook. PASTRES, Institute of Development Studies, Sussex and the European University Institute in Florence. Reproduced with permission and accessed online at https://pastres.files.wordpress.com/2023/11/photovoice-guide-digital.pdf (Photo by Malicha, used with permission of the ERC PASTRES project)

You read the side-bar again, and then see the caption given by the curator in this thought experiment: LIKE SO MUCH IN LIFE (YOURS INCLUDED), PASTORALISM IS NOT ONE WAY ONLY. That sticks, and for how much time depends on you.

III

What makes this kind of curatorial practice such a useful entry point is that even the most radical exhibitions guided by progressive politics have to finds ways to work within the conventional “white cube” constraints of rooms, floors and walls upon which to hang rectangles or display against.

By extension, the most radical development recastings also have to be in productive tension with current ways of seeing things.

–Take another illustration hanging on the walls of this exhibition, that of the policy cycle:

But you, like every other member of the public to this exhibition, are your own curator in the sense of having to ask: What’s missing here in this graphic? When it comes to really-existing policies, programs and projects, “a simplified” just doesn’t hack it. You know each stage is bedeviled by details and contingencies. Indeed, once other viewers make the same complaint, you’ve established a very effective critique of anything like a “normal cycle.”

The upshot? Here too the viewing publics understand there is no one way to exhibit project performance. The stages sequence together differently for viewers who see different details and have different criteria for whether what works or not, what fails or not. Curators who exhibit to illustrate more continuity than is there might be better thought of as exhibiting their own confirmation bias.

IV

So what?

By way of an answer, consider the following quote, seemingly unrelated and without any representation, written on a wall in the last room of this exhibition:

I propose to categorize policies according to their intended goal into a three-fold typology: (i) compensation policies aim to buffer the negative effects of technological change ex-post to cope with the danger of frictional unemployment, (ii) investment policies aim to prepare and upskill workers ex-ante to cope with structural changes at the workplace and to match the skill and task demands of new technologies, and steering policies treat technological change not simply as an exogenous market force and aim to actively steer the pace and direction of technological change by shaping employment, investment, and innovation decisions of firms.

R. Bürgisser (2023), Policy Responses to Technological Change in the Workplace, European

Commission, Seville, JRC130830 (accessed online at https://retobuergisser.com/publication/ecjrc_policy/ECJRC_policy.pdf)

By this point you’ve seen all the representations in the preceding rooms of pastoralists who are being displaced from their herding sites, in these cases by land encroachment, sedentarization, climate change, mining, and the like.

But the free-standing quote presses you think further: What are the compensation, investment and steering policies of government to address this displacement. That is, where are the policies to: (1) compensate herders for loss of productive livelihoods, (2) upskill herders in the face of eventually losing their current employment, and (3) efforts to steer the herding economies and markets in ways that do not lose out if and where new displacement occurs?

You look around the room to find an answer. What do you see? Nothing is what you see. With the odd exception that proves the rule, no such national policies are hanging anywhere or standing in place.

That too sticks in your mind as you exit.

V

But what comes after the critical analysis of culture? What goes beyond the endless cataloguing of the hidden structures, the invisible powers and the numerous offences we have been preoccupied with for so long? Beyond the processes of marking and making visible those who have been included and those who have been excluded? Beyond being able to point our finger at the master narratives and at the dominant cartographies of the inherited cultural order? Beyond the celebration of emergent minority group identities, or the emphatic acknowledgement of someone else’s suffering, as an achievement in and of itself?

Irit Rogoff quoted in Claire Louise Staunton (2022). The Post-Political Curator: Critical Curatorial Practice in De-Politicised Enclosures. PhD Dissertation. Royal College of Art, London (accessed on line at https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/5278/1/06.02.23_Post-correction%20Thesis%20FULL.pdf)

In answer, what comes after are efforts to curating publics for what we–and they as their own curators–recast as small-d “development.”