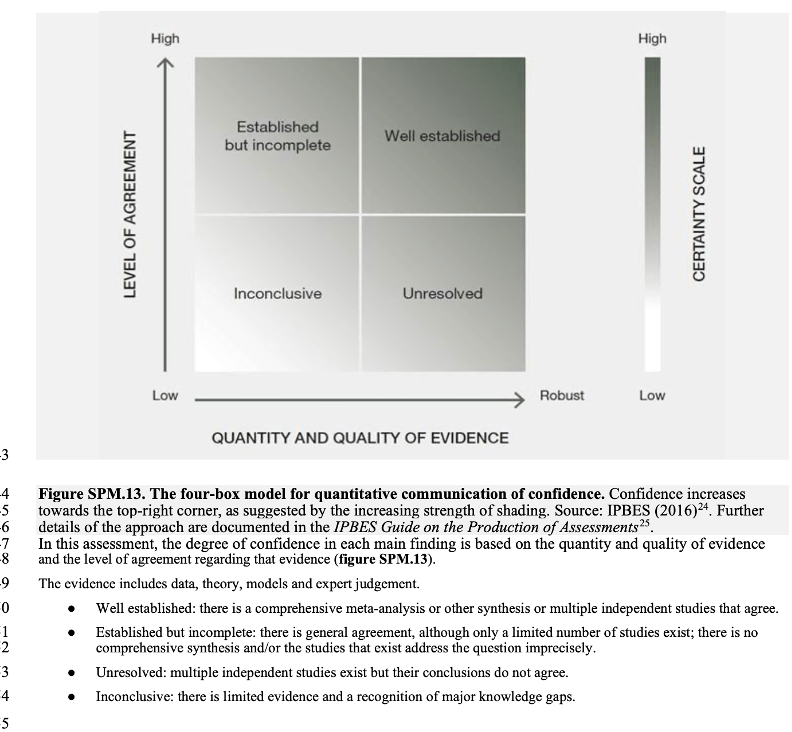

Assume you come across the following typology, a 2 X 2 table identifying four types of confidence you have over empirical findings for policy analysis and policymaking:

It’s a fairly easy to question the above. Do we really believe that well-established evidence, even as defined, and high certainty are as tightly coupled? In fact, each dimension can be problematize in ways relevant to policy analysis and policymaking.

But the methodological issue is to compare like to like.

That is, interrogate the cells of the above typology using the cells of another typology whose overlapping dimensions also problematize those of the above. Consider, for example, the famous Thompson-Tuden typology, where the key decisionmaking process is a function of agreement (or lack thereof) over policy-relevant means and ends:

This latter world has a few surprises for the former one. Contrary to the notion that inconclusive evidence is “solved” by more and better evidence, the persistence of “inconclusive” (because, say, of increasing urgency and interruptions) implies lapsing eventually into decisionmaking-by-inspiration. So too the persistence of “unresolved” or “established but incomplete” shuttles, again and again, between majority-rule and compromises. More, what is tightly coupled in the latter isn’t “evidence and certainty” as in the former, but rather the beliefs over evidence with respect to causation and the preferences for agreed-upon ends and goals.

In case it needs saying, methodological like-to-like comparisons of typologies need not stop at a comparison of two only. Social and organizational complexity means the more the better by way of finding something usefully tractable.