1. When it comes to pastoralists. . .

2 The computational irrationality of The Tragedy of the Commons

3. Colin Strang or Garrett Hardin: Which one do you believe?

4. Borana sedentarization

5. Environmental livestock-tarring

6. Rethinking early warnings for drought

7. “Curating publics,” not just “facilitating pastoralist development”

8. A different lens to recast pastoralist mobility: “logistical power from below”

9. Pastoralists as social figures

10. Dust and herders viewed from the paradigm of repair

11. Pastoralists as witnesses-protagonists

12. Imputing property values in pastoralist systems as a way of making more visible the tensions under the climate emergency

13. Expanding the early warning systems for geoengineering interventions: a pastoralist indicator

14. Journal article as manifesto: an example involving Horn of Africa livestock

15. How might digital nomadism recast a research agenda for pastoralism?

16. The moral economy of pastoralists seen through the Levy-Cordelli lens of investment

17. When pastoralists are more like occupiers than residents only (newly added)

1. When it comes to pastoralists, . . .

I have in mind those who regret the passing of pastoralism as if it were a singular institution with its own telos, agency and life-world. It wasn’t and it isn’t. When was the last time these people asked herders their party affiliation? When was the last time they really treated the pastoralist as neoliberal citizen?

These commentators are like the freshwater biologists who consider Lethenteron appendix (the American brook lamprey) and Triops cancriformis (a type of tadpole shrimp) to be evolutionary success stories because the organisms haven’t evolved. By this measure, the best pastoralists are like feisty little tardigrades, those near-microscopic (another “marginal”!) organisms that survive in the most hostile environments on the planet.

I also have in mind those stylized narratives of depastoralizing, deskilling, disorganizing and dewebbing the pastoralist life-world, leaving behind corpse-pastoralism, flogged by conflicts, mummified by inequality, buried at sea in waves of liquid modernity, dissolved by the quicklime of disaster capitalism and speculative finance, always harboring worse to come.

I also have in mind the hangover notion that policy and procedure are at every turn subordinate to state power, that politicians and officials are nothing but the state’s secretariat to capitalists, that capitalisms have entirely colonized every nook and cranny of the life-worlds, and that we have surrendered our minds entirely to politics, such as they are.

I have in mind the disturbing parallel between those who want to save Planet Earth by means of straightforward treatments like stopping fossil fuel or methane-producing cattle and, on the other hand, Purdue Pharma’s promotion of OxyContin as treatment for chronic pain that masked the lethal addiction to this kind of “straightforward” medicine.

Last but not least, I have in mind the remittance-sending household member who is no more at the geographical periphery of a network whose center is an African rangeland than was Prince von Metternich in the center of Europe, when he said, “Asia begins at the Landstraße” (the outskirts of Vienna closest to the Balkans). You can stipulate Asia begins here and Africa ends there, but good luck in making that stick within and across national policies.

Methodological upshot: It cannot be said often enough that you mustn’t expect reproduction of the same even when reversion to the mean occurs.

2. The computational irrationality of The Tragedy of the Commons

Here is my rearrangement of quotes from a recent piece by philosopher, Akeel Bilgrami:

[I]t is often felt that. . .the commons is not doomed to tragedy since it can be ‘governed’ by regulation, by policing and punishing non-cooperation.

Who can be against such regulation? It is obviously a good thing. What is less obvious is whether regulation itself escapes the kind of thinking that goes into generating the tragedy of the commons in the first place. . . .

To explain why this is so, permit me the indulgence of a personal anecdote. It concerns an experience with my father. He would sometimes ask that I go for walks with him in the early morning on the beach near our home in Bombay. One day, while walking, we came across a wallet with some rupees sticking out of it. My father stopped me and said somewhat dramatically, ‘Akeel, why shouldn’t we take this?’ And I said sheepishly, though honestly, ‘I think we should take it.’

He looked irritated and said, ‘Why do you think we should take it?’ And I replied, what is surely a classic response, ‘because if we don’t take it, somebody else will’. I expected a denunciation, but his irritation passed and he said, ‘If we don’t take it, nobody else will’. I thought then that this remark had no logic to it at all. Only decades later when I was thinking of questions of alienation did I realize that his remark reflected an unalienated framework of thinking. . . .

From a detached perspective, what my father said might seem like naïve optimism about what others will do. But the assumption that others will not take the wallet if we don’t, or that others will cooperate if we do, is not made from that detached point of view. It is an assumption of a quite different sort, more in the spirit of ‘let’s see ourselves this way’, an assumption that is unselfconsciously expressive of our unalienatedness, of our being engaged with others and the world, rather than assessing, in a detached mode, the prospects of how they will behave. . . .

The question that drives the argument for the tragedy of the commons simply does not compute. . .

https://www.thephilosopher1923.org/post/what-is-alienation

To repeat: The question that drives the argument for the Tragedy of the Commons simply does not compute in such cases. In the latter, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is computationally irrational.

3. Colin Strang or Garrett Hardin: Which one do you believe?

M: You seem now to be in the paradoxical position of saying that if everyone evaded [e.g., paying taxes], it would be disastrous and yet no one is to blame. . . .But surely there can’t be a disaster of this kind for which no one is to blame.

D: If anyone is to blame it is the person whose job it is to circumvent evasion. If too few people vote, then it should be made illegal not to vote. If too few people volunteer, you must introduce conscription. If too many people evade taxes, you must tighten up your enforcement. My answer to your ‘If everyone did that’ is ‘Then some one had jolly well better see that they don’t’. . .

Colin Strang, philosopher, “What If Everyone Did That?”, 1960

Eight years later, we get Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Common, whose answer to “What if every herder did that?” is: “We must admit that our legal system of private property plus inheritance is unjust–but we put up with it because we are not convinced, at the moment, that anyone has invented a better system. The alternative of the commons is too horrifying to contemplate. Injustice is preferable to total ruin.”

Get real: We’ve always known the better question is: Whose job is it to ensure overgrazing doesn’t happen? Which, to be frank, continues to be the same as asking: Whose job is it to define “overgrazing”?

NB: One of the biting ironies is that Hardin’s explicit piece on morality took no account of Strang’s essay, which was among the most cited and anthologized in collections on ethics and morality at that time.

4. Borana sedentarization

I

Unlike many economists of his generation or later ones, G.L.S. Shackle was preoccupied with how economic agents make real-time decisions in situations so uncertain that no one, including agents, knows the range of options and their probability distributions upon which to decide.

In response, Shackle produced an analysis based on possibilities rather than probabilities and what is desirable or undesirable rather than what is optimal or feasible.

For Shackle, possibility is the inverse of surprise (the greater an agent’s disbelief that something will happen, the less possible it is from their perspective). Understanding what is possible depends on the agents thinking about what they find surprising, namely, identifying what one would take to be counter-expected or unexpected events that could arise from or be associated with the decision in question. Once they think through these alternative or rival scenarios, the agents should be better able to ascribe to each how (more or less) desirable or undesirable a possibility it is.

These dimensions of possibility (possible to not possible) and desiredness (desirable to undesirable) form the four cells of a Shackle analysis, in which the agents (think: decisionmakers) position the perceived rival options. Their challenge is to identify under what conditions, if any, the more undesirable-but-possible options and/or the more desirable-but-not-possible options could become both desirable and possible. In doing so, they seek to better underwrite and stabilize the assumptions for their decisionmaking.

II

Let’s move now from the simplifications to a complexifying example. Consider the following conclusion from an investigation of sedentarization among Borana pastoralists:

Although in the case of this study we can speculate generally about what has prompted the sedentarization adaptation from quantitative analysis and the narratives of local residents, we do not sufficiently understand the specific institutions and information that individuals, households, and communities have utilized in their adaptation decision making. Only in understanding the mechanisms of such inter-scale adaptations can national and state governments work toward increasing community agency and promoting effective and efficient local adaptive capacity.

https://doi.org/10.5751/ ES-13503-270339

Such an admission is much needed in the policy and management research with which I am familiar. Thus the point made below should not be considered a criticism of the case study findings. Here I want to use the Shackle analysis to push their conclusion further.

III

Briefly stated, what and where are now undesirable adaptations in Ethiopian pastoralist sedentarization–by government? by communities? by others?–that: were not possible then and there but are now; or were possible then and there but are not now? More pointedly, where else in Ethiopia, if at all, are conditions such that those undesirable adaptations of sedentarization are now considered more desirable by pastoralist communities themselves?

If there is even one case of a community where the undesirable has now become desirable and where the now-desired is (still) possible, then sedentarization is not a matter of, well, settled knowledge.

5. Environmental livestock-tarring

A modest proposal:

Assume livestock are toxic weapons that must be renounced in the name of climate change. Like nuclear weapons, they pose such a global threat that nations sign the Livestock Non-Proliferation Treaty (LNPT). It’s to rollback, relinquish or abolish livestock, analogous to the Non Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Treaty.

How then would the LNPT be implemented, i.e., what are the ways to reduce these toxic stockpiles of dangerous animals?

–If the history of the nuclear proliferation treaty is our guide, the livestock elimination focus quickly becomes the feasibility and desirability of particular elimination scenarios. Scenarios in the plural because context matters, e.g., the way South Africa renounced nuclear weapons could not be the same ways Belarus and Ukraine relinquished them, etc.

So assume livestock elimination scenarios are just as differentiated. We would expect reductions in different types of intensive livestock production to be among the first priority scenarios under LNPT. After that, extensive livestock systems would be expected to have different rollback scenarios as well. For example, we would expect livestock to remain where they have proven climate-positive impacts: Livestock are shown also to promote biodiversity, and/or serve as better fire management, and/or establish food sovereignty, and/or enable off-rangeland employment of those who would have herded livestock instead, etc.

–In other words, we would expect livestock scenarios that are already found empirically widespread.

Which raises the important question: Wouldn’t the LNPT put us right back to where we are anyway with respect to livestock?

–Finally, in case there is any doubt about the high disesteem in which I hold the notion of a LNPT, let me be clear:

If corporate greenwashing is, as one definition has it, “an umbrella term for a variety of misleading communications and practices that intentionally or not, induce false positive perceptions of a system’s environmental performance,” then environmental livestock-tarring is “an umbrella term for a variety of misleading communications and practices that intentionally or not, induce false negative perceptions of a system’s environmental performance with respect to livestock.”

Source: For one of many examples of environmental livestock-tarring, see https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/12/replace-animal-farms-micro-organism-rewilding-food-precision-fermentation-emissions

6. Rethinking early warnings for drought

Bells were increasingly used not only to summon people to church, but also to provide another prompt for a belief act to those laity who had not attended: the major bells were to be rung during the Mass at the moment of consecration of the Host, and from the late twelfth century onwards we find texts calling upon lay people to kneel and adore where ever they were at that moment…

John Arnold (2023). Believing in belief: Gibbon, Latour and the social history of religion. Past & Present, 260(1): 236–268. (https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtac012)

I

I suggest that early warnings promulgated as part of official drought management systems are designed to be bells in just the above sense: People are to demonstrate their belief in the warnings when warned. They are to take action then and there because of them.

But, as Arnold also reminds us, demonstration of obedience always entails the possibility of failure. Obeying might not work. Heeding the warning might not have been effective anyway.

Indeed, some early warning systems are designed to fail because they are also meant for non-believers. The latter include those who subscribe to other types of warnings (e.g., https://pastres.org/2023/05/12/local-early-warning-systems-predicting-the-future-when-things-are-so-uncertain/).

This matters because the stakes are high when it comes to drought for both believers and non-believers. How so?

II

It is important to understand the conditions under which the designers themselves don’t believe in their own bell-ringing systems. In their article, “Drought Management Norms: Is the Middle East and North Africa Region Managing Risks or Crises?,” Jedd et al (2021) examine the efficacy official systems in the MENA region. They conclude:

Drought monitoring data were often treated as proprietary information by the producing agencies; interagency sharing, let alone wider publication, was rare. Government officials described the following reasons for this approach. First, it could create pressure on decision-makers to take action (politicizes the issue). Second, intervention measures are costly, and so, taking measures creates strong and competing demands for financial resources from agencies and/or ministers (increase political transaction costs). Therefore, given existing policies and institutions in the countries, it is unclear to what extent drought decision-making processes would be improved or expedited with increased transparency of monitoring information. . . .

This creates a difficult puzzle: In order to mitigate future drought losses, a clear depiction of current conditions must be made publicly available. However, publishing these data may require that agencies take on the burden of allocating relief if the release of this very information coincides with a future drought crisis.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1070496520960204

III

So then the obvious policy and management question is: When it comes to the efficacy of early warnings for droughts, who do you want to start with: the believers or the non-believers?

7. “Curating publics,” not just facilitating pastoralist development

I

You’ve done all that research on livestock herders. You’ve collected so much information to better government policy and management. You know all the critiques of big-D development. But no one is listening. No one is acting on the findings and insights.

What do you do now and instead, whoever is listening or not? One answer: undertake the practice of curating publics as a part of your work.

I am suggesting that practices–subaltern, “development,” really-existing–can be curated so as to create new publics or, better yet, counterpublics. We want them collected and illustrated in ways that stick in these peoples’ minds, regardless of the dominant development narratives already there.

II

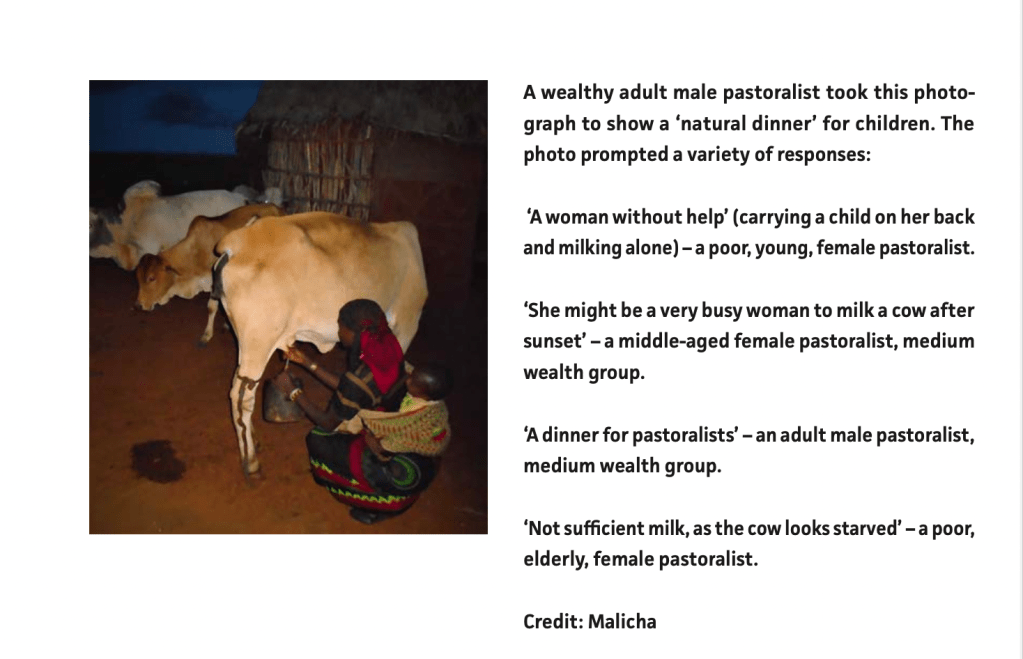

For example, enter the first of several rooms in our thought-experiment exhibition, “Rethinking Pastoralism Today.” On the wall there, you find pictured with a sidebar and attribution:

Source: S. Bose (2023). Photovoice With Pastoralists: A Practical Guidebook. PASTRES, Institute of Development Studies, Sussex and the European University Institute in Florence. Reproduced with permission and accessed online at https://pastres.files.wordpress.com/2023/11/photovoice-guide-digital.pdf (Photo by Malicha, used with permission of the ERC PASTRES project)

You read the side-bar again, and then see the caption given by exhibition’s curator: LIKE SO MUCH IN LIFE (YOURS INCLUDED), PASTORALISM IS NOT ONE WAY ONLY. That sticks in your mind, and you suspect those of others.

III

What makes this kind of curatorial practice such a useful entry point is that even the most radical exhibitions guided by progressive politics have to finds ways to work within the conventional “white cube” constraints of rooms, floors and walls upon which to hang rectangles or display against.

By extension, the most radical development recastings have to be in productive tension with current ways of seeing things as well.

–Take another illustration hanging on the walls of this exhibition, that of the policy cycle:

But you, like every other visitor to this exhibition, are your own curator in the sense of having to ask: What’s missing here in this representation? When it comes to actual policies, programs and project, “simplified” just doesn’t hack it. You know from experience, as do like viewers, that each stage is bedeviled by details and contingencies. Indeed, once other viewers also understand these details and contingencies, you’ve established a very effective critique of anything like a “normal cycle.”

The upshot? A viewing public that understands there is no one way to exhibit project performance. The stages hang together differently for viewers who see different details and have different criteria for whether what works or not, what fails or not. Curators who exhibit to illustrate family resemblances that are not seen by viewers as their own curators might be better thought of as exhibiting their own confirmation bias.

IV

So what?

But what comes after the critical analysis of culture? What goes beyond the endless cataloguing of the hidden structures, the invisible powers and the numerous offences we have been preoccupied with for so long? Beyond the processes of marking and making visible those who have been included and those who have been excluded? Beyond being able to point our finger at the master narratives and at the dominant cartographies of the inherited cultural order? Beyond the celebration of emergent minority group identities, or the emphatic acknowledgement of someone else’s suffering, as an achievement in and of itself?

Irit Rogoff quoted in Claire Louise Staunton (2022). The Post-Political Curator: Critical Curatorial Practice in De-Politicised Enclosures. PhD Dissertation. Royal College of Art, London (accessed on line at https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/5278/1/06.02.23_Post-correction%20Thesis%20FULL.pdf)

In answer, what comes after are efforts to curating publics for what we–and they as their own curators–recast by way of pastoral development.

8. A different lens to recast pastoralist mobility: “logistical power from below”

The following are excerpts from Biao Xiang (2023), “Logistical power and logistical violence: lessons from China’s COVID experience,” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies (accessed online at DOI: 10.1080/24761028.2023.2285022).

Logistical power, be it from above or below, is defined in the article as the “capacity to initiate, coordinate, and stop mobility”:

A state gains infrastructural power by building roads, but does not acquire significant logistical power unless it can collect real-time traffic data, monitor all vehicles, and communicate with individual drivers on the move. More importantly, the concepts of infrastructural power and logistical power point to different analytical questions. Infrastructural power is by definition state power, and the concept is meant to explain how and why modern states, wielding much less despotic power than traditional rulers, can effectively govern societies of tremendous scale and complexity; and why the state and civil society have both become more powerful in the modern times. Infrastructural power enables modern states to govern through society instead of over society. Logistical power, in comparison, has its origin in social life. In most parts of human history, it is the marginal groups – nomads, migrants, hill tribes, petty traders, vagabonds and many others – which are most capable of exercising logistical power. The critical question associated with the concept of logistical power is not how state and society gain more power at the same time, but rather how state concentrate logistical power at the cost of people’s logistical power, in which process society becomes fragmented and loses its capacity of coordinating mobility.

Logistical power is the ability to coordinate mobility, and can be possessed by state and non-state actors. Logistical violence is state coercion through forced (im)mobility. Logistical power from below, namely citizen’s capacity to move and to form networks beyond government control, was a driving force behind economic reforms in the 1980s. By the 2010s, logistical power from above – the coordination of mobility by larger corporations and the state in particular – had become the dominant means of organizing the mobility of people, goods, money, and information.

So what?

While appearing inescapable due to its infrastructural and logistical power, the state has profound difficulty in controlling people’s thoughts, emotions, or communications. When talking to each other, citizens can construct a lifeworld of common sense, interpersonal trust, and mutual assistance. Such a lifeworld may provide a base for the capacity to refuse and resist forces like logistical violence.

State-sponsored sedentarization is logistical violence, the chief resistance to which is and remains the logistical power of pastoralists who move their herds and/or household members outside these settlements.

9. Pastoralists as social figures

We consider a timeless model of a common property resource (CPR) in which N herdsmen are able to graze their cattle. The model has been constructed deliberately along orthodox economics lines. . . .We begin with a timeless world. Herdsmen are indexed by i (i = 1, 2, …, N). Cattle are private property. The grazing field is taken to be a village pasture. Its size is S. Cattle intermingle while grazing, so on average the animals consume the same amount of grass. If X is the size of the herd in the pasture, total output – of milk – is H(X, S), where H is taken to be constant returns to scale in X and S.

Dasgupta, P. (2021), The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. London: HM Treasury: 221 (internal footnotes deleted)

After such bloodless abstractions, it’s a wonder more readers don’t rush to the anthropological literature for descriptions of really-existing pastoralists and their herding practices.

The methodological problem, though, is that there’s really-existing, and then there’s really-existing. There are pastoralists interviewed and quoted. Then there’s the social figure of the pastoralist, a composite assembled by a researcher to represent the typical features of the pastoralists who have been studied.

All well and good, if you understand that the use of social figures extends significangtly beyond the confines of anthropology or the social sciences. Social figures “potentially have all the characteristics which would be considered character description in literary studies,” notes a cultural sociologist, adding, “unlike ideal types, for example, which are written with a clear heuristic goal in a scientific context, social figures can also appear in public debate or be described in literary texts.”

So what? “For theorizing, this means. . .attention must be paid to a good figurative description: Is the figurative description vivid, descriptive and, as a figure, internally consistent? Does it accurately reflect the social context to which it refers? Therefore, the criteria to assess quality in theorizing must be complemented by literary criteria.”

And one of those literary conventions helps explain why the social figure of the pastoralist today is frequently compared and contrasted to the social figure of the pastoralist in the past. “[T]here are often antecedent figures for a social figure. . .The current social figure can then be understood as an update of older social figures.”

A small matter, you might think, and easily chalked up to “this is the way we do historial analysis.” It is not, however, a slight issue methodologically, when comparing your pastoralist interviewees today with the social figures of pastoralists in the past ends up identifying “differences” that are more about criteria for rather than empirics in “really-existing.”

Source. T. Schlechtriemen (2023). “Social figures as elements of sociological theorizing.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory (accessed online at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1600910X.2023.2281233)

10. Dust and herders viewed from the paradigm of repair

“What if the rise of China,” [Jerry] Zee poignantly asks, “were to be approached literally, through the rise of China into the air?” Amidst official and popular accounts of China’s authoritarian ruling, Zee’s Continent in Dust is a striking example of how to write about China and Chinese politics otherwise. The book focuses on how weather events—specifically, those involving dust, aerosols, and particulate matter—are sites for political breakdown and emergence, revealing that the Chinese political system is anything but static.

Zee opens the book with a story of a resettled ex-herder family, whose herds have allegedly overgrazed pastures in inner Mongolia. This, in turn, has resulted in the spread of dust storms, or “wind-sand” (feng sha 风沙).2 Controlling the dust flow has become a state priority, and so these ex-herders have adapted: having left behind their old jobs, they now drive civil servants across fragile dunes, airdrop seeds, and stabilize sand. These state-contracted environmental engineering jobs, however, are only “semipredictable,” leaving the ex-herders caught in “a state of constantly frustrated anticipation.”

Still, how does this offer new insight into China at large? Because, by following the dust, Zee reveals that the plight of these ex-herders is not because of the popularly accepted idea of “a neoliberalization of the socialist state.” Instead, the wind-sand shows how bureaucrats view ex-herders as both a source of “social instability” in rural frontiers and as an on-demand workforce that can furnish state sand-control programs. In other words, ex-herders represent China’s “experiment in governing,” swept in an atmosphere of “windfall opportunities for work and cash,” a departure from the declining pastoral economy. This story is not about the rise of neoliberal China but, instead, the “delicately maintained condition of quietude” deemed harmonious and stable enough for the Chinese state.3

https://www.publicbooks.org/protean-environment-and-political-possibilities/

Hands-on work is necessary to cultivate the awareness that architecture cannot be contained within the plot of land.

The way I came to this awareness was cleaning the facades of buildings with my own two hands. This work constitutes the ongoing series The Ethics of Dust, which I began in 2008. These artworks emerged from the intersection of architecture and experimental preservation. I wanted to preserve the dust that would normally be thrown out, because it seemed to me, intuitively at first, that this dust contained important information about architecture’s environmental footprint. This dust, which you can see deposited as dark stains on facades, comes in large measure from the boilers of buildings, as well as electric power plants and traffic. The smoke produced as a byproduct when we heat, cool, and electrify buildings is as much a condition of possibility for architecture as concrete or steel. The airborne particles we call smoke or dust are therefore an architectural material. Yet smoke cannot be contained inside the plot of land. To manipulate this material requires new ways of caring for architecture that encompass this larger territory. It invites us to imagine how to care for the atmosphere as an airborne built environment.

https://placesjournal.org/article/repairing-architecture-schools/

What if the built environments of the many different pastoralists include all manner of dust from herding livestock, cooking in the compound, transport speeding down dirt roads, this year’s droughts. intermittent sand storms, and the sudden dust-devils? What if architectural schools are moving from a pedagogy of new construction (think: development) to repair and renovation of the already built? What do these new generations of researchers offer by way of advice to really-existing pastoralists today?

One answer from the last citation: “It is important, also, to listen and learn from communities who inhabit the buildings and environments that need repair, because they know best what is broken.” To put it another way, only in a some versions of particulate matter is dust broken.

11. Pastoralists as witnesses-protagonists

I

In my reading, narratives of pastoralism divide into three major groups. There are the studies of pastoralism long past (think: Wilfred Thesiger). I’ve also read anthropological studies from the 1950s and 60s that share a nostalgia for pasts now threatened by modernizing pressures.

The second group is everything that Thesiger and colonial-era anthropologists are not. To cut this long story short, today’s pastoralists are imbricated through and through by overlapping settler-colonial, racial and global capitalisms. There is, though, a deep irony in the fact that the thorough-going critiques of capitalism end up shadow pricing a past thought to be outside the cash-nexus.

The third group is for me more interesting and recent. The literature here seeks to stand in the pastoralists’ marginal(ized) positions and from there speak to the dominant economies and politics at the center. Some of this draws pastoralists to the center by demonstrating how their practices and ways of thinking are shared by, if not have positive implications for, center-based economics, banking, and pandemics (I have in mind the recent work of Ian Scoones and his PASTRES colleagues at IDS Sussex).

I want, however, to focus on a fourth group of narratives, and frankly one I’m not sure exists like the others. Here the narratives are those where contemporary pastoralists are “witnesses-protagonists,” much along the lines of the character, “witness-protagonist,” found in certain period novels.

II

In her 2024 Modern Language Quarterly article, “On the Origins of the Witness-Protagonist,” Anastasia Eccles gives examples of novels where such characters are found. For our purposes, these are less important than the features she ascribes to this character type (I quote at length):

This essay focuses on the “witness-protagonist”: a recessive but still identifiably major character who observes the developments of the main plot from a position on its margins. Such characters are familiar from modernist novels, but this essay turns back to a formative stage in their history to recover their forgotten political significance. . . .

The witness-protagonist took shape during a period of mass revolution abroad and democratic mobilization in Britain in which constituencies lacking formal recognition claimed the power to remake the structures of collective life. These historical developments turned the phenomenon of “unwarranted” participation into a pressing matter of public debate—and a basic condition of modern political subjectivity. The characters considered here tend to strike readers as illegitimate subjects who do not quite fit into or live up to their assigned roles. Instead of anchoring the whole, as we might expect protagonists to do, they call the form of the whole—its boundaries and its internal arrangement—into question. In their curiously unstable narrative position, they illuminate the formal conditions of democratic agency. . . .

Such a figure thus embodies the apparent paradox of a peripheral center or a major minor character. . .

The witness-protagonist, then, is a character whose status in the novel as a whole is somehow in question. We might say that these characters pose problems of or for form, insofar as form is taken to mean some principle of underlying fit or coherence among the novel’s parts. The signs of this problem are evident in the commentary surrounding these characters, which so often takes the form of a struggle to fix or locate or categorize a figure who does not quite behave like a normal protagonist. . . .

If the novel form projects an imagined community or potential body politic, these novels draw attention to that community’s grounds and limits. By focusing on characters whose station in the novel is anything but secure, they underscore the contingency of any particular arrangement of the collective. . .

Accessed online through https://read.dukeupress.edu/modern-language-quarterly/article-abstract/doi/10.1215/00267929-11060495/385703/On-the-Origins-of-the-Witness-Protagonist?redirectedFrom=fulltext

I don’t know about you, but I suspect I’m not the only one who sees pastoralists we’ve studied or read about in terms of: being at the margins, but still difficult to locate with respect to the dominant narrative; not like the protagonists at the center, though still clearly a center of gravity interacting with that bigger narrative; but so insecurely as to call into question the dominant narrative(s).

III

An example I have in mind is that of a 2023 Annual Review of Anthropology article, “Financialization and the Household,” by Caitlin Zaloom and Deborah James. Although not explicitly in the preceding terms, the quote below captures this sense of speaking substantively and interactively about the center from the perspective of householders, including rural and poor households at the margins:

Finance and the household are a pair that has not received sufficient attention. As a system, finance joins citizens, states, and global markets through the connections of kinship and residence. Householders use loans, investments, and assets to craft, reproduce, attenuate, and sever social connections and to elevate or maintain their class position. Householders’ social creativity fuels borrowing, making them the target of banks and other lenders. In pursuit of their own agendas, however, householders strategically deploy financial tools and techniques, sometimes mimicking and sometimes challenging their requirements. Writing against the financialization of daily life framework, which implies a one-way, top-down intrusion of the market into intimate relations, we explore how householders use finance within systems of social obligations. Financial and household value are not opposed, we argue. Acts of conversion between them produce care for the self and others and refashion inherited duties. Social aspiration for connection and freedom is an essential force in both financial lives and institutions.

https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-anthro-052721-100947

Imagine if the very first article you ever read about global financialization began with the preceding quote. Imagine that those articles you actually have read up to this point on global financialization now must be re-read as slightly-off-center by comparison. What you thought was the plot all along isn’t the plot with which you could have started.

Source. Ian Scoones (2024). Navigating Uncertainty: Radical Rethinking for a Turbulent World. Polity Press.

12. Imputing property values in pastoralist systems as a way of making more visible the tensions under the climate emergency

Major issues affecting the US housing market are the effect of the climate emergency on property values:

As climate disasters hit with greater intensity and frequency, the economic effects will be felt not only as the underlying assets are damaged or destroyed, . . .but also as those experiences, and expectations of similar ones to come, are “priced in” to the judgments of what homes in floodplains, on the storm-exposed coasts, and in the wildland-urban interface are worth. Those homes could become, in effect, economically worthless even before they are physically uninhabitable. This would then put pressure on areas that are, for the time being, environmentally stable, driving up property values to the benefit of some, while creating economic hardships for others. . . .They are left either stuck in place—with assets that are increasingly difficult to insure. . .and potentially financially underwater— or face a decline in the proceeds available to secure housing elsewhere, let alone to build wealth.

(accessed online at https://academic.oup.com/socpro/advance-article/doi/10.1093/socpro/spae074/7932449, my bolding)

So too you find declinist narratives about pastoralist areas rendered economically worthless under capitalism even before they are rendered physically uninhabitable by the climate emergency.

But of course drylands have noncalcuable use values for pastoralists, whatever is happening to calculated economic values. More, some asset values were evident in commercial transactions long before the advent of any capitalism. And in case it needs saying (also see the above link), property values have always been a social construction within and beyond markets and beyond the quantitative, a fact no less true for herders and their resources, including the drylands relied upon.

So too is the climate emergency bringing into better view not just the changes but also the reciprocal tensions when imputing property values, e.g.:

Overall, we show that reciprocal linkages between environmental change and migration clearly exist in the studied rural communities in Ethiopia, which are mediated by various factors occurring at the micro, meso, and macro level (Table 1). These factors cover biophysical, socioeconomic, and institutional aspects. Remarkably, although not surprisingly, our research revealed that most identified factors can act in opposite directions. Hence, they can trigger or accelerate changes, just as they can hamper or slow them down. For example, in northern Ethiopia, unfavorable environmental conditions for agriculture, including increased drought frequency, unreliable rainfall, and advanced land degradation, can increase migration needs and aspirations by undermining the viability of agricultural livelihoods. However, these conditions also tend to lower migration abilities by decreasing agricultural income and hence, financial resources required for migration. Conversely, favorable environmental conditions, such as relatively stable rainfall during the cropping season in “a good year,” can decrease migration needs and aspirations and enable migration via agricultural income (for more details, see below the description of pathways A and B). The precise impact mechanisms significantly depend on a variety of additional mediating factors at the macro, meso, and micro level. . .

(accessed online at https://ecologyandsociety.org/vol28/iss3/art15/)

I want to suggest that, in the case of pastoralist systems, focusing on property (noncalculable use and calculated exchange) values and the tensions their social constructions reveal, balance or evade is a better methodological strategy than appeals to “commodification” or “marketization,” as if the latter terms were differentiated enough.

13. Expanding the early warning systems for geoengineering interventions: a pastoralist indicator

It’s a commonplace to argue that scientists and experts need to be talking to and engaging much more with the traditional knowledge folks. What’s less often the case are examples of mutual benefit of doing so. One priority area for reciprocity, I suggest, is that of geoengineering.

Geoengineering is offered up as a last-ditch effort to save the planet in the midst of its very real climate emergency. Even so, one must wonder: What better way to bring the governments of the world to their collective knees than solutions like those that would ballon the skies with mirrors and sulfur dioxide and the seas with chemical changes to capture more carbon, all because the climate emergency has left humanity no choice—no alternative—but to be unreliable on unprecedented scales?

Such indeed is the rationale for having in place robust monitoring and evaluation (M&E) systems of the geoengineering interventions. Now of course, much of the current debate is about the unintended consequences of geoengineering and about the early warning systems for monitoring and evaluating them. But those consequences are almost exclusively dominated by concerns of global North and South experts and scientists.

I suggest that the major priority of governments and the regulators of geoengineering initiatives–and there is no stopping this experimentation!–is to ensure that the early warning systems for droughts and bad weather still in operation among pastoralists and agriculturists of the developing world are also included and canvassed.

The latter are, I believe, a quite specific case where the intersection of measurable and nonmeasuable indicators is of mutual benefit to far more than the presiding scientists and experts in the Global North and South. For my part, I wonder what will be the decrease (or increase for that matter) in the murders of local “rainmakers” (forecasters) because of geoengineering.

On the murder of rainmakers during drought, please see Isao Murahashi (2024), “Climate change or local justice? On frequent drought and regicide in South Sudan.” Presentation given on August 8 2024 as a part of the International Hyflex Sessions, “Living in the Anthropocene, living in uncertainty: Reconfiguring development and humanitarian assistance as ‘care’ with relational approach,” held at IDS Sussex.

14. Journal article as manifesto: an example involving Horn of Africa livestock

To be clear: I like the manifesto below; I agree with it. But that agreement is not because it’s also published as a journal article. Instead, I believe it because, as a manifesto, it demands change now in terms I understand and appreciate historically.

Since my argument depends on the definition of “manifesto” I use, here’s mine:

Always layered and paradoxical, [a manifesto] comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries— something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. . .This is a form that asks readers to suspend their disbelief, and so like any piece of theater, it trades on its own vulnerability, invites our complicity, as if only the quality of our attention protects it from reality’s brutal puncture. A manifesto is a public declaration of intent, a laying out of the writer’s views (shared, it’s implied, by at least some vanguard “we”) on how things are and how they should be altered. Once the province of institutional authority, decrees from church or state, the manifesto later flowered as a mode of presumption and dissent. You assume the writer stands outside the halls of power (or else, occasionally, chooses to pose and speak from there). Today the US government, for example, does not issue manifestos, lest it sound both hectoring and weak. The manifesto is inherently quixotic—spoiling for a fight it’s unlikely to win, insisting on an outcome it lacks the authority to ensure.

L. Haas (2021). “Manifesto Destiny: Writing that demands change now.” Bookforum accessed online at https://www.bookforum.com/print/2802/writing-that-demands-change-now-2449

In 2023, Mark Duffield and Nicholas Stockton published, “How capitalism is destroying the Horn of Africa: sheep and the crises in Somalia and Sudan,” in the peer-reviewed Review of African Political Economy (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03056244.2023.2264679). To its credit, the Review publishes “radical analyses of trends, issues and social processes in Africa, adopting a broadly materialist interpretation of change.” And what a breadth of fresh air this article is.

First, its tone is direct, its language unequivocally materialist in the great manner of yesterday, its focus is on the marginalized, and, equally important, how could we not want change after reading this?

We present in outline an historically and empirically grounded explanation for the post-colonial destruction of the nation states of Somalia and Sudan. This is combined with a forecast that the political de-development of the Horn, and of the Sahel more generally, is spreading south into East and Central Africa as capitalism’s food frontier, in the form of a moving lawless zone of resource extraction. It is destroying livelihoods and exhausting nature. Our starting point is Marx’s argument that the historical growth and the continuing development of capitalism is facilitated through what he called ‘primitive accumulation’. With regard to the current situation in the Horn, there is a sorry historical resonance with the violent proto-capitalist land clearances that took place from the sixteenth century onward in England, Ireland and Scotland and then in North America. While today, as in Darfur, this may be classified as genocide, the principal purpose of land clearances is to convert socially tilled soils and water resources used for autonomous subsistence into pastures for intensive commercial livestock production, which now in Somalia and Sudan amounts to nothing short of ‘ecological strip mining’.

To repeat, how could you (we) not want radical change when reading further:

. . .we argue that the trade is intimately connected with the deepening social, economic and ecological crisis of agro-pastoralism in the region and the way that livestock value is now realised. Underlying the empirical data is the intensification of an environmentally destructive mode of militarised livestock production that, primarily involving sheep, is necessarily expansive, land-hungry, livelihood destroying and population displacing. Sustained by raw violence and strengthened by United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi investment in Red Sea port infrastructure, the Horn and the Gulf are locked into a deadly destruction–consumption embrace.

More, there is a singular cause and it is clear: “This internationally facilitated mode of appropriation, with its associated acts of land clearance, dispossession and displacement, is the root cause of the current crisis.” Nor is there anything really complex about this:

The depth and cruel nature of the changes in Sudan and Somalia’s agro-pastoral economies cannot reasonably be attributed only to environmental change, scarcity-based inter-ethnic conflict, or avaricious generals per se. To lend these arguments weight, some hold that they combine to produce a ‘complex’ emergency. The only complexity, however, is the contortions necessary to fashion a parallel universe that usefully conceals the rapacity of capitalism. Particularly cynical is the claim, for example, that Somalia’s long-history of de-development is the result of climate-change-induced drought. It is no accident that the same international powers and agencies fronting this claim have, for decades, been active players in the Horn’s de-development.

You cannot imagine how much I want to believe these words! And I take that to be a good measure of just how effective a manifesto this manifesto is, at least for someone like myself.

Manifestos are their own public genre, whatever the publication venue. This is not a policy memo whose second sentence after the problem statement is the answer to: What’s to be done and how? But then we would never look to manifestos for the devil in the details, would we?

15. How might digital nomadism recast a research agenda for pastoralism?

What if we were to reverse the usual comparison and ask: What value, if any, does the topic of digital nomadism have to add our understanding of pastoralist mobility and movements?

In answer, the lens of digital nomadism that I apply is from Emanuele Sciuva’s 2025 article, “Geographies of Digital Nomadism: A research agenda” published in Geography Compass (online at https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gec3.70016). In the interests of brevity, we stay with the article’s abstract:

The focus has shifted from just the nomads themselves to also considering the destinations they inhabit and the broader spatial implications of their movement. This review sets out a research agenda based on emerging discussions about the geographies of digital nomadism, organized around four main thematic areas. The first cluster of scholarly works examines how digital nomads are understood at the crossroads of work‐life, leisure and lifestyle mobility perspectives. The second part includes studies that explore how states are crafting migration regulations and programs to attract digital nomads, along with the difficulties that nomads face in navigating these evolving regulatory landscapes. The third cluster of scholarship investigates the intricate interplay between digital nomadism and housing, focussing on the rise of a medium‐term rental market and diverse housing solutions tailored to digital nomads, while cautioning against the potential gentrifying effects of these emerging markets. Finally, the fourth segment of research examines the socio‐economic infrastructural changes arising from the growing presence of digital nomadism within urban settlements.

Right off the bat, there is a focus on livestock grazing and herding itineraries and shifts (see Krätli, 2015) that comes with first and foremost “considering the destinations they inhabit and the broader spatial implications of their movement.” Second, there is the decentering of any notion of “traditional” in the contemporary “work-life, leisure and lifestyle mobility perspectives”. Third, it’s housing and shelter, not (re)settlements per se, that also move center-stage in the analysis, which I take to include the structures–be they rental, squatter, public–lived in by household members sending back key remittances to their livestock-herding members.

Fourth, as for the mix of positive and negative regulations on mobility, regulations seek, in Emanuele Sciuva’s words, “not only to regulate who can or cannot move, enter, or remain in a place but also operate. . .[to incentivize] mobile individuals to self‐discipline according to desired traits like self‐sufficiency, consumer citizenship, and depoliticized mobility” That is, when was the last time researchers treated pastoralists as consumers, voters and citizens? Fifth and to stop here, there is also now another primary question: How are pastoralists and their herds changing all manner of local and national infrastructures (e.g., via private investments), not least of which are in urban or peri-urban areas?

Your reading Emanuele Sciuva’s article will show the point-to-point comparison between those nomads and these pastoralists to be imperfect and uneven (e.g., with respect to the internet’s role). But such comparisons are now in my opinion too suggestive by way of policy and management implications to dismiss outright.

Other source

Krätli, S. (2015) Valuing Variability: New Perspectives on Climate Resilient Drylands Development, London: IIED http://pubs.iied.org/10128IIED.html

16. The moral economy of pastoralists seen through the Levy-Cordelli lens of investment

Below I commit an injustice to the insights of three publications: (1) Tahari Shariff Mohamed (2022). The Role of the Moral Economy in Response to Uncertainty among Borana Pastoralists of Northern Kenya, Isiolo County, PhD dissertation, Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex: Falmer, Brighton UK; (2) Jonathan Levy (2025). The Real Economy: History and Theory, Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ; and (3) Chiara Cordelli (2025). “What Is the Wrong of Capitalism?” American Political Science Review 1–16.

Yet the Levy/Cordelli perspective on the central role of investments–not accumulation, not markets, not prices, but investment–in real economies is an excellent lens with which to add to and extend the already more nuanced work now underway on moral economies.

Let me start with Mohamed’s work. She makes many fine points about really-existing moral economies, but we have space for probing only one–her connection between diversification of pastoralist livelihoods and investments (I bold terms to be parsed through the Levy/Corelli lens):

Pastoralists rely on fundamental practices such as herd mobility, livestock species and livelihood diversification, and investing in social relations in order to navigate livestock production uncertainties. Within these practices, particular moral economy practices, centred on collective redistribution of resources remain significant. The thesis identifies five types of moral economy practice. In the more remote pastoral setting, with intensified insecurity and limited state and institutional presence, practices of redistribution and comradeship are central. In the more urban pastoral setting, with a proliferation of institutions, markets, diversification and investment, institutionalised support and collective crisis management through the use of newly important technologies are seen. Contrary to the assumption that the moral economy is waning due to social stratification and individualisation, the thesis finds that moral economies persist, and new forms are emerging. (p.xvi)

Here, the moral economy emerges through galvanising household members to engage in various income-generating activities to cover costs such as purchasing feeds and paying hired labourers. It is the shared responsibilities and duties to collectively contributes remittances and other income from diverse economies to save the livelihood that embodies moral economy. It embodies what Ellis referred to as ‘non-economic’ aspect of social relations that regulate resource use and access to ensure survival (Ellis, 2000a). It differs from the traditional moral economy of mobilising household members to provide labour support; instead, household members engage in diverse livelihood activities to generate much-needed income that is then invested in sustaining the herd. (p.138)

. . .there is a ‘non-economic’ component of diversification, including social relations, norms and values that regulate income distribution and access. For instance, the case studies presented in chapter seven on women and intra-household diversification illuminated the power dynamic and the transforming gender relations that defined how pastoralists survived in a more urbanising setting. Equally, the opening quote of this section alludes to ‘we’, meaning that it is not one person who diversifies; instead, it is a combined effort by individuals within the family that pull resources and share remittance to manage the livelihood. Thirdly, diversification espouses the moral economy practices defined in this study as a network of relations based on trust that enhances access to resources for survival in the face of uncertainties. I argue that pastoralists establish external connections through economic ties and symbiotic relationships in order to generate a reliable flow of goods, including feeds, labour and market access to survive unpredictable pastoral production. (p.154)

Yet, if I understand Levy and Corelli correctly, what is “non-economic” in the above is economic by virtue of the centrality of investment (e.g., “investing in social relations”). “What is the first act that creates the economy?,” asks Levy in an interview. “It is neither production nor exchange (market or otherwise). It is the storing of wealth over time, with which I associate with investment.” Livestock as a store of wealth with which to save and from which to invest has been one paradigmatic example.

For Levy, the centrality of investment applies to what he calls the real economy–which, importantly, need not be a capitalist one (e.g., p.21). This is important because capitalist economies have a feature that moral economies must mitigate. In Cordelli’s argument,

. . .under capitalism both the amount and the direction of production are driven by a distinctively future-oriented investment process. Such process is guided by a specific mode of economic valuation—capitalization—which consists in attributing monetary value to assets in the present on the basis of their expected future profitability, rather than their inherent productivity, or the labor expenditure that went into producing them. Since, under capitalism, what will be produced crucially depends on investment, investment is left to private markets, and economic valuation is oriented to future profits, capitalism structurally entails a radical loss of collective control over, and involvement in, the creation and valuation of the future. Capitalism privatizes the power to build the future, and to decide according to which values it should be built. It leaves such power to profit-oriented investment markets. (p.3)

Little of this description will trouble those insisting that capitalism has commodified and marketized every major aspect of contemporary pastoralism. The passage however should trouble those who see the investment in social relations as a way to mitigate or forestall such thorough-going commodification and marketization.

Yes, the latter are increasing, though one must keep in mind Mohamed’s caution about assuming everywhere the “waning moral economy”. Whatever, the bigger question remains, Why hasn’t the waning gone even faster?

Cordelli provides one answer, namely, livestock are not capital unless they can be capitalized: “[S]avings cannot per se count as capital, because they are not capitalized, and the inherent productivity of the means of production is insufficient to make them capital” (p. 6-7). That is, livestock as that walking savings bank isn’t capital just because that store of wealth is based in livestock production; it’s because investment in social relations has kept their flows of benefit from being altogether discounted into economic net present value for pastoralists.

So what? What’s the upshot for pastoralist policy and management? Best to let Levy have the last word in terms of understanding real economies:

Categorically speaking there is nothing wrong with the methodological use of abstractions, mathematical exposition, modeling, building up explanations from individual choice and behavior, extreme scaffolding assumptions, or statistical inference. It may be true that economics at times suffers from being incorrect. The critique I am most invested in making, however, is that even when correct economics also suffers from being intolerably incomplete. (p.16)

Sources

Donald Judt (2025). “Storage, Investment, and Desire: An Interview with Jonathan Levy” Journal of the History of Ideas Blog (accessed at https://www.jhiblog.org/2025/02/24/storage-investment-and-desire-an-interview-with-jonathan-levy/)

Mohamed’s thesis can be found at: https://sussex.figshare.com/articles/thesis/The_role_of_the_moral_economy_in_response_to_uncertainty_among_Borana_pastoralists_of_Northern_Kenya_Isiolo_County/23494508?file=41202650

Cordelli’s article can be found at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/american-political-science-review/article/what-is-the-wrong-of-capitalism/CD320C659A33C006C6562D363FD5D954

17. When pastoralists are more like occupiers than residents only (newly added)

I

I couldn’t help thinking of Kristin Ross’s The Commune Form when reading Navigating Violence and Negotiating Order in the Somalia–Kenya Borderlands by Patta Scott-Villiers, Alastair Scott-Villiers and others.

At first reading, though, these are two very different books about very different sites. Here is how Ross’s publisher, Verso, describes her essay:

When the state recedes, the commune-form flourishes. This was as true in Paris in 1871 as it is now whenever ordinary people begin to manage their daily lives collectively. Contemporary struggles over land–from the ZAD at Notre-Dame-des-Landes to Cop City in Atlanta, from the pipeline battles in Canada to Soulèvements de la terre–have reinvented practices of appropriating lived space and time. This transforms dramatically our perception of the recent past.

Rural struggles of the 1960s and 70s, like the “Nantes Commune,” the Larzac, and Sanrizuka in Japan, appear now as the defining battles of our era. In the defense of threatened territories against all manners of privatization, hoarding, and infrastructures of disaster, new ways of producing and inhabiting are devised that side-step the state and that give rise to unprecedented kinds of solidarity built on pleasurable, fruitful collaborations. These are the crucial elements in the present-day reworking of an archaic form: the commune-form that Marx once called “the political form of social emancipation,” and that Kropotkin deemed “the necessary setting for revolution and the means of bringing it about.”

Here in contrast is the Summary from Scott-Villiers et al:

This working paper examines how communities along the Somalia–Kenya border navigate a landscape of war. Over decades of conflict–including civil war, insurgency, and counterinsurgency–local people have relied on their own means of governance and mutual support to repair the damage and maintain life and livelihood. The study draws on people’s reflections on their ‘middle way’, a system rooted in tradition by which they both govern themselves and do their best to avoid the dangers of the war. The informal order blends customary institutions, negotiated agreements, and far-reaching social networks to provide basic public goods and maintain the common good.

So indeed, the two publications have very important differences.

II

Yet what connects them for me is Ross’s point about the protracted occupy-movements that interest her:

Occupations that endure for so long require of the occupants a ceaseless ingenuity to come up with new and creative ways of inhabiting the conflict. Fighting about a place is not the same as fighting for an idea. Place-specific struggles create a political situation that really calls for a clear-cut existential choice. . .The Weelaunee Forest outside Atlanta will continue to be a forest, or it will become a militarized training ground for police. . .

This notion that people have now come to occupy a territory indefinitely strikes me as what some of those in the borderlands of Kenya and Somalia are also undergoing.

It might be useful to think of some pastoralists there less as residents only of drylands in which they and their families have long lived. Rather, think of them more as inhabiting conflicts which render them, like others also now there, as occupants of what are best understood as shifting borderlands. Yes, you still see them as residents, but they also act as occupiers of a territory now claimed by others as well.

For example, according to one interviewee in Scott-Villiers et al:

My name is Burhaan. I’m a pastoralist. It is the zakat season [when “charitable contributions” are made]. There is a lot of push from Al-Shabaab around the villages collecting the tax. You know this zakat has stayed for some time now, and we know what it is. I used to pay to my relatives who are poor, but now I pay to Al-Shabaab. The first time they took the tax, a few years ago, I was herding on the Kenya side and Al-Shabaab came to collect the zakat. They have people who do the counting for them. They know how many are in each herd. They tied two camels of mine. I went to the local police boss, the Officer in Charge of Security (OCS), and told him – my camels are taken by Al-Shabaab. The OCS asked me: ‘How many camels did you have, 30? And then they tied how many, two?’ Then he asked, what will they do next? I said, they will go with them and then they will come back after one year. And then the OCS asked: ‘Between now and then, what will happen to you?’ Nothing will happen to me, I replied. If I have paid my tax, my camels can graze anywhere. I’m not faced by any threat from them. That is when the OCS said: ‘If my unit goes after Al-Shabaab, I may lose soldiers. If two camels can guarantee your safety and the security for a year, it is a good deal!’ I went straight to those who took away my camels and negotiated – these animals are not all mine, I said. This is a herd that is pooled together by many people. Then they told me: ‘If you have issues to raise, you can go to a place called Busar and lodge a complaint. We have mechanisms for addressing grievances.’ I pleaded with them: ‘I don’t know that place, I’ve never been there, I’m from this Kenya side of the border.’ And then they released one camel back to me. It was a waiver. And then after from that day I have complied with paying zakat to Al-Shabaab.

III

So what? So what if pastoralists are occupants of borderlands along with others, notably the Kenya military and Islamic insurgents?

The answer that Ross’s work implies is more than interesting: Alliances by pastoralists with other very different occupiers that shift over time and sites can be ways to defend that occupied territory and appropriate it for uses and practices of each.

And why is that important? Because, as Ross also points out, defence and appropriation are not the same as resistance: “Resistance, quite simply, means letting the state set the agenda. Defence, on the other hand, is grounded in a temporality [namely, protracted conflict] and a set of priorities by the local community in the making.” Note: “in the making.”

Sources

Ross, K. (2024). The Commune Form: The Transformation of Everyday Life. London: Verso.

Scott-Villiers, P.; Scott-Villiers, A. and the team from Action for Social and Economic Progress, Somalia (2025) Navigating Violence and Negotiating Order in the Somalia– Kenya Borderlands, IDS Working Paper 618, Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. (Accessed online at https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/articles/report/Navigating_Violence_and_Negotiating_Order_in_the_Somalia_Kenya_Borderlands/2871

22 thoughts on “Other fresh perspectives on pastoralists and pastoralism: 17 brief cases (last newly added)”