On March 26, 2024, about 0129 eastern daylight time, the 984-foot-long Singapore-flagged cargo vessel (containership) Dali was transiting out of Baltimore Harbor in Baltimore, Maryland, when it experienced a loss of electrical power and propulsion and struck Pier 17, the southern pier that supported the central span of the continuous through-truss of the Francis Scott Key Bridge. A portion of the bridge subsequently collapsed into the river, and portions of the pier, deck, and truss spans collapsed onto the vessel’s forward deck (see figure 1). . .

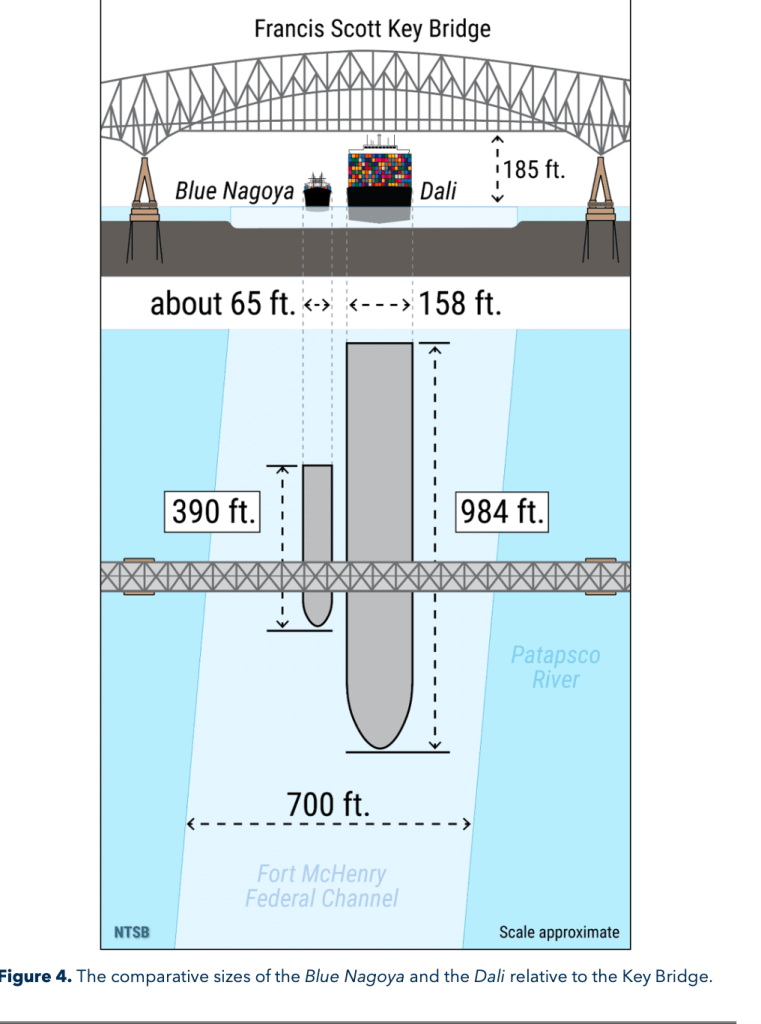

. . . The Key Bridge’s pier protection was struck in 1980 when the 390-foot-long Japan-flagged containership Blue Nagoya, which had a displacement or weight about one-tenth that of the Dali, collided with Pier 17 following a loss of steering about 600 yards from the bridge; see figure 4 for a size comparison of the Blue Nagoya to the Dali. . .

From the Marine Investigation Report for this accident (accessed online at https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/MIR2510.pdf)

Even I was taken aback by the two figures, and I study this stuff! Just look at the differences in containership sizes and you’d think even more disasters must lie in waiting wherever such infrastructures have not grown in size and scope relative to the demands placed on them.

Now, of course, there are those who would blame my perceptiions on all those distorting cognitive biases–anchoring, salience, selection–as if they were trained incapacities on my part. But guys, we’ve learned to worry about problems where physical capacity of infrastructures do not grow with their physical demand!

Even though true, that point doesn’t go far enough. The more important point is the empirical insight from the high reliability literature: A complex sociotechnical system is reliable only until its next failure. That is, we need to know more about how the current system is managed in real time beyond its technology and design in order to avoid failures.

Or in case of the tanker, we need to know, inter alia, how experienced harbor pilots bringing the tankers into port manage these tankers under those current conditions (see a pilot’s perspective on the accident at https://theconversation.com/ive-captained-ships-into-tight-ports-like-baltimore-and-this-is-how-captains-like-me-work-with-harbor-pilots-to-avoid-deadly-collisions-226700). I mention harbor pilots because their definitions of a “near miss”–which they’ve experienced–and my definition of near miss–just look at how close the tanker’s antennae are to figure 4!–vary significantly.

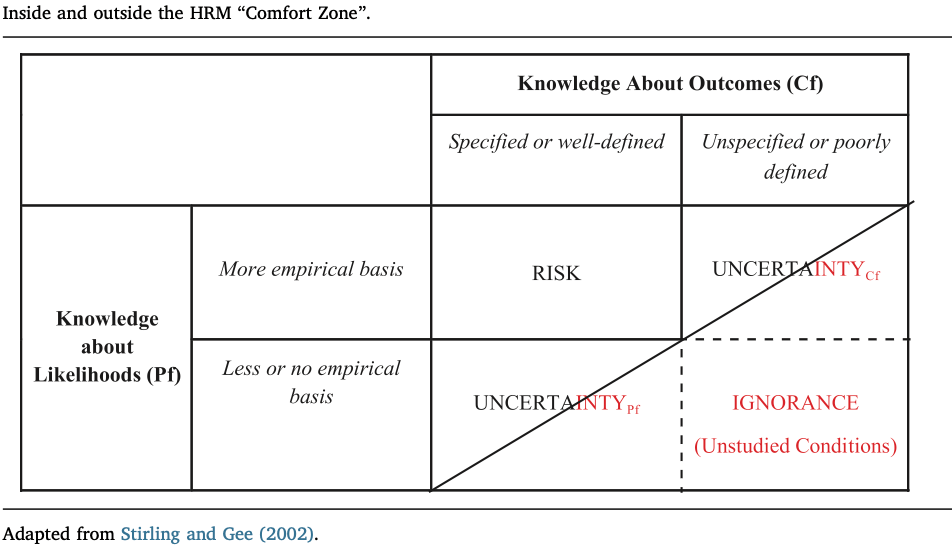

This difference may well be more than “What are to me very, very narrow safety buffers are to them manageable ones.” I haven’t studied harbor pilots, but the infrastructure operators we studied distinguish between uncertainties to be managed and unstudied conditions in which not to operate. Operators we’ve talked with call this their “comfort zone,” though as one control room supervisor hastened to add, “I’m always uncomfortable.” How so is illustrated in the following table:

High reliability management professionals we study practice vigilance to stay out of the red area below the diagonal and stay within the area above it—a stylized version of their comfort zone. To maintain this level of comfort they tolerate some uncertainty about outcomes (Cf) matched by having high confidence in some probabilities (Pf). They also tolerate some uncertainty about probabilities by having higher confidence that consequences are limited. Management within these uncertainties is in either case supported by team situation awareness in the control room. In other words, the professionals seek to avoid unknown unknowns by extending but limiting their management to known unknowns—uncertainties with respect to outcomes and probabilities they can tolerate as part of their comfort zone as risk managers (Roe and Schulman 2018).

This is a very important distinction for safety management in other critical infrastructures. Are there such reliability professionals when it comes to AI safety? Complex sociotechnical systems have by definition complex technical cores, about which real-time operators do not have full and complete causal knowledge. So too by extension opaque AI algorithms are a concern, but not a new concern. Unstudied and unstudiable conditions have always been an issue under mandates for the safe and continuous provision of a critical infrastructure’s service in the face of various and variable task environments. The key issue then is: What uncertainities with respect to probabilities and consequences are they managing for when it comes to AI safety so as to avoid operating ignorantly?

Source.

E. Roe and P.R. Schulman (2018). “A reliability & risk framework for the assessment and management of system risks in critical infrastructures with central control rooms. Safety Science 110 (Part C): 80-88.

3 thoughts on “Some safety extensions from the high reliability literature”