1. From a high reliability management perspective, regulation for safety in large socio-technical systems is dispersed. The regulation of critical infrastructures for system safety is not just what the regulators do; it is also what the infrastructures do in ways that their regulator of record can’t do on its own. Those who have the real-time information must fulfill regulatory functions with respect to system safety that the official regulator is not able to fulfill.

2. The dispersed functions of regulations for system safety put a premium on understanding real-time practices of control room operators and field staff in these large systems. Safety, if it is anything, is found in practices-as-undertaken, i.e., “it’s operating safely.” This means safety is best understood more as an adverb, not as a noun. You can no more make safety than you can make fish from fish soup.

3. It makes little sense then for critics to conclude that regulators are failing because formal regulations are not being complied with, if the infrastructures are managing in a highly reliable fashion and would not be doing so if they followed those regulations to the letter. In practical terms, this means there is not just the risk of regulatory non-compliance by the infrastructure, there is also the infrastructure’s risk of compliance with incomplete regulations.

4. Another way to put such examples is that, when it comes to managing safely, there is a major difference between error avoidance and risk management. Not taking advantage of opportunities to improvise and communicate laterally is a known error to avoid in immediate emergency response. Unlike risks to be managed more or less, these errors are to be avoided categorically, yes or no. What is most important about error avoidance is missing those real opportunities that shouldn’t or can’t be missed where the logic, clarity and urgency of “this is or is not responding safely” are evident.

5. If points 1 – 4 hold, the challenge then is to better understand the institutional niche of critical infrastructures, that is, how infrastructures themselves function in allocating, distributing, regulating and stabilizing system safety (and reliability) apart from the respective government regulators of record.

6. With that in mind, turn now to the relationship between system risk and system safety, specifically: regulating risk in order to ensure system safety. For some, the relationship is explicit, e.g., increasing safety barriers reduces risk of component or system failure.

In contrast, I come from a field, policy analysis and management, that assumes safety and risk are to be treated differently, unless otherwise shown in the case at hand. Indeed, one of the founders of my profession (Aaron Wildavsky) made a special point to distinguish the two. The reasons are many for not assuming that “reduce risks and you increase safety” or “increase safety and you reduce risks.” In particular:

However it is estimated, risk is generally about a specified harm and its likelihood of occurrence. But safety is increasingly recognized, as it was by an international group of aviation regulators, to be about “more than the absence of risk; it requires specific systemic enablers of safety to be maintained at all times to cope with the known risks, [and] to be well prepared to cope with those risks that are not yet known.”. . .In this sense, risk analysis and risk mitigation do not actually define safety, and even the best and most modern efforts at risk assessment and risk management cannot deliver safety on their own. Psychologically and politically, risk and safety are also different concepts, and this distinction is important to regulatory agencies and the publics they serve. . . .Risk is about loss while safety is about assurance. These are two different states of mind.“

Danner and Schulman, 2019

7. So what?

That informed people continue to stay in earthquake zones and sail in stormy seas even if they can move away from both tells you something about their preferences for system safety, let alone personal safety. For it is often safety with respect to the known unknowns of where they live and work versus safety with respect to unknown-unknowns of “getting away.” Unknowns, not risks.

Let’s shift gears to a different example and extension.

On March 26, 2024, about 0129 eastern daylight time, the 984-foot-long Singapore-flagged cargo vessel (containership) Dali was transiting out of Baltimore Harbor in Baltimore, Maryland, when it experienced a loss of electrical power and propulsion and struck Pier 17, the southern pier that supported the central span of the continuous through-truss of the Francis Scott Key Bridge. A portion of the bridge subsequently collapsed into the river, and portions of the pier, deck, and truss spans collapsed onto the vessel’s forward deck (see figure 1). . .

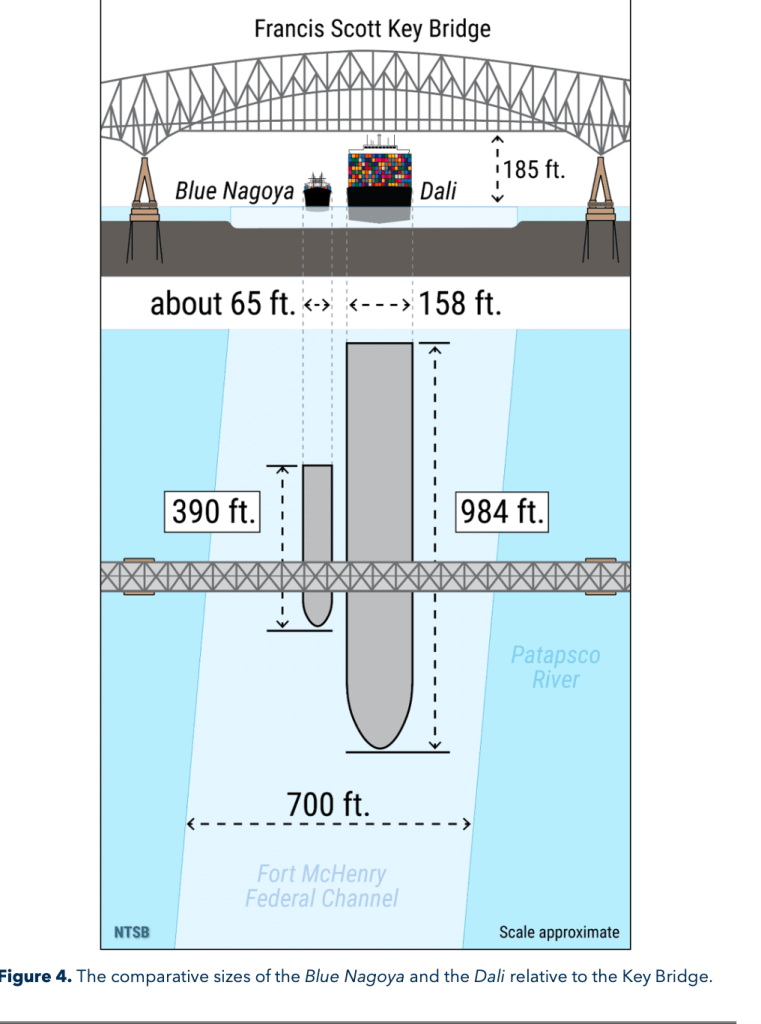

. . . The Key Bridge’s pier protection was struck in 1980 when the 390-foot-long Japan-flagged containership Blue Nagoya, which had a displacement or weight about one-tenth that of the Dali, collided with Pier 17 following a loss of steering about 600 yards from the bridge; see figure 4 for a size comparison of the Blue Nagoya to the Dali. . .

From the Marine Investigation Report for this accident (accessed online at https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/MIR2510.pdf)

Even I was taken aback by the two figures, and I study this stuff! Just look at the differences in containership sizes and you’d think even more disasters must lie in waiting wherever such infrastructures have not grown in size and scope relative to the demands placed on them.

Now, of course, there are those who would blame my perceptions on all those distorting cognitive biases–anchoring, salience, selection–as if they were trained incapacities on my part. But people, we’ve learned to worry about problems where physical capacity of infrastructures do not grow with their physical demand!

Even though true, that point doesn’t go far enough. The more important point is the empirical insight from the high reliability literature: A complex sociotechnical system is reliable only until its next failure. That is, we need to know more about how the current system is managed in real time beyond its technology and design in order to avoid failures. How managing safely means more than regulating for safety.

Or in case of the tanker, we need to know, inter alia, how experienced harbor pilots bringing the tankers into port manage these tankers under those current conditions (see a pilot’s perspective on the accident at https://theconversation.com/ive-captained-ships-into-tight-ports-like-baltimore-and-this-is-how-captains-like-me-work-with-harbor-pilots-to-avoid-deadly-collisions-226700). I mention harbor pilots because their definitions of a “near miss”–which they’ve experienced–and my definition of near miss–just look at how close the tanker’s antennae are to figure 4!–vary significantly.

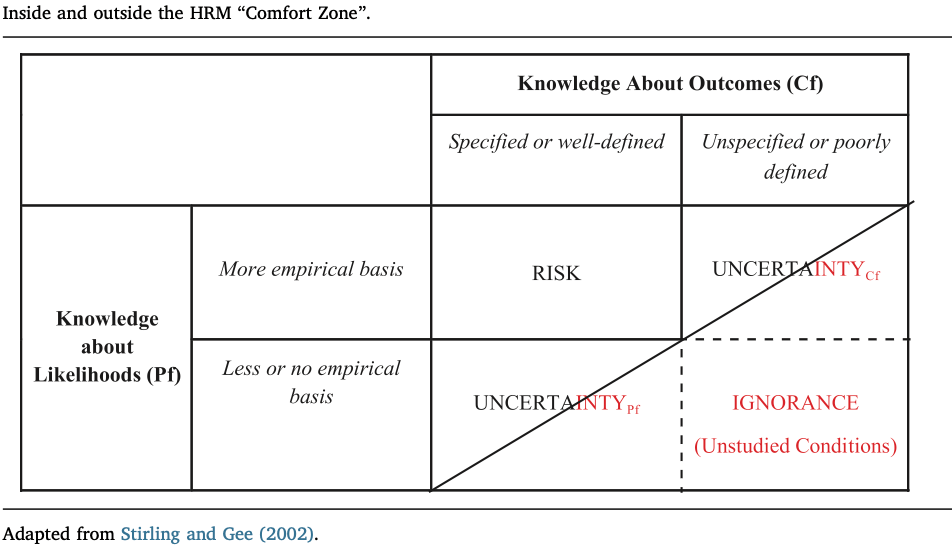

This difference may well be more than “What are to me very, very narrow safety buffers are to them manageable ones.” I haven’t studied harbor pilots, but the infrastructure operators we studied distinguish between uncertainties to be managed and unstudied conditions in which not to operate. Operators we’ve talked with call this their “comfort zone,” though as one control room supervisor hastened to add, “I’m always uncomfortable.” How so is illustrated in the following table:

High reliability management professionals we study practice vigilance to stay out of the red area below the diagonal and stay within the area above it—a stylized version of their comfort zone. To maintain this level of comfort they tolerate some uncertainty about outcomes (Cf) matched by having high confidence in some probabilities (Pf). They also tolerate some uncertainty about probabilities by having higher confidence that consequences are limited. Management within these uncertainties is in either case supported by team situation awareness in the control room. In other words, the professionals seek to avoid unknown unknowns by extending but limiting their management to known unknowns—uncertainties with respect to outcomes and probabilities they can tolerate as part of their comfort zone as managers of operational risks and safety (Roe and Schulman 2018).

This is a very important distinction for managing safely in other critical infrastructures. Are there such reliability professionals when it comes, say, to “AI safety” (more formally, when it comes to the adverbial properties of performing safely or not)?

Complex sociotechnical systems have by definition complex technical cores, about which real-time operators do not have full and complete causal knowledge. So too by extension opaque AI algorithms are a concern, but not a new concern. Unstudied and unstudiable conditions have always been an issue under mandates for the safe and continuous provision of a critical infrastructure’s service in the face of various and variable task environments. The key issue then is: What uncertainties with respect to probabilities, uncertainties and consequences are they managing for when it comes to “AI safety” so as to avoid operating (acting, performing) ignorantly? Or more formally, when does avoiding error in real time require more than regulating for the management of risks?

Sources

Danner, C., and P. Schulman (2019). “Rethinking risk assessment for public utility safety regulation.” Risk Analysis 39(5): 1044-1059.

E. Roe and P.R. Schulman (2008). High Reliability Management. Stanford University Press, Stanford CA.

————————- (2018). “A reliability & risk framework for the assessment and management of system risks in critical infrastructures with central control rooms. Safety Science 110 (Part C): 80-88.

To my knowledge, philosophers Gilbert Ryle and Michael Oakeshott, are among those who first discussed the importance of recasting “thinking” and “behavior” in terms of adverbs rather than as common nouns.