In my profession, policy analysis and public management, theory and method aren’t separate when it comes to actual, really-existing practices. They’re unavoidably fused for practitioners with whom I’ve worked.

This would be a banal observation if it weren’t for the fact that many practices mean many methods-cum-theories, and the virtue of the many is having more means to reframe, redescribe, recalibrate, revise, readjust, repurpose, rescript, recalibrate, reorient–in a word, recast–difficult policy and management issues. No guarantees, but you get the point: A little theory, as it has been said, can go a long way in practice, and the many methodological considerations across them can take you even further.

Below are thirteen very different examples of what this means by way of practice:

1. Key method questions in complex policy and management

2. Methodological implications of using triangulation in complex policy and management.

3. Methodologically, analogies without counter-cases are empty signifiers

4. Peer review: another area where error avoidance is the method for reliability management

5. Not all the “can’s, might’s, may’s, or could’s” add up to one single “must” in policy analysis

6. But in policy advocacy, conditions of “could and might” do lead to proposals that “require and would”

7. To paraphrase Wittgenstein, an infinite regress explains nothing

8. The Achilles heel of conventional risk management is the counterfactual

9. What “calling for increased granularity” means

10. The methodological relevance of like-to-like comparisons for policy and management

11. The methodological importance of “and-yet” counternarratives

12. The cross-cutting methodological fault-line in Infrastructure Studies, and why it matters

13. Seven differences in method that matter for reliable policy and management

1. Key method questions in complex policy and management

I

A young researcher had just written up a case study of traditional irrigation in one of the districts that fell under the Government of Kenya’s Arid and Semi-Arid Lands (ASAL) Programme. (We’re in the early 1980s.) I remember reading the report and getting excited. Here was detailed information about really-existing irrigation practices and constraints sufficient to pinpoint opportunities for improvement there.

That was, until I turned the page to the conclusions: What was really needed, the author stated, was a country-wide land reform.

Huh? Where did that come from? Not from the details and findings in the report!

This was my introduction to “solutions” in search of problems they should “solve.” Only later did I realize I should have asked him, “What kind of land reform for whom and under what conditions at your research site?”

II

Someone asserts that this policy or approach holds broadly, and that triggers you asking:

- Under what conditions?

- With respect to what?

- As opposed to what?

- What is this a case of?

- What are you–and we–missing?

Under what conditions does what you’re saying actually hold? Risk or uncertainty with respect to what failure scenario? Settler colonialism as opposed to what? Just what is this you are talking about a case of? What are you and I missing that’s right in front us?

2. Methodological implications of using triangulation in complex policy and management

I

Triangulation is the use of multiple methods, databases, theories, disciplines and/or analysts to converge on what to do about the complex issue. The goal is for analysts to increase their confidence–and that of their policy audiences–that no matter what position they take, they are led to the same problem definition, alternative, recommendation, or other desideratum. Familiar examples are the importance in the development literature of women and of the middle classes.

In triangulating, the analyst accommodates unexpected changes in positions later on. If your analysis leads you to the same conclusion regardless of initial positions that are already orthogonal, then the fact you must adjust that position later on matters less because you have sought to take into account utterly different views from the get-go.

Everyone triangulates, ranging from cross-checking of sources to formal use of varied methods, strategies and theories for convergence on a shared point of departure or conclusion. Triangulation is thought to be especially helpful in identifying and compensating for biases and limitations of any single approach. Obtaining a second (and third. . .) opinion or soliciting the input of divergent stakeholders or ensuring you interview key informants with divergent backgrounds are common examples.

Detecting bias is fundamental, because reducing, or correcting and adjusting for bias is one thing analysts can actually do. To the extent that bias remains an open question for the case at hand, it must not be assumed that increasing one’s confidence automatically or always increases certainty, reduces complexity, and/or gets one closer to the truth of the matter.

II

Return now to our starting point: The approaches in triangulation are chosen because they are, in a formal sense, orthogonal. This has another methodological implication: The aim is not to select the “best” from each approach and then combine these elements into a composite that you think better fits or explains the case at hand.

Why? Because the arguments, policies and narratives for complex policy and management already come to us as composites. Current issue understandings have been overwritten, obscured, effaced and reassembled over time by myriad interventions. To my mind, a great virtue of triangulation is to make their “composite/palimpsest” nature clearer from the outset.

To triangulate asks what, if anything, has persisted or survived in the multiple interpretations and reinterpretations that the issue has undergone over time up to the point of analysis. Indeed, failure to triangulate can provide very useful information. When findings do not converge across multiple and widely diverse metrics or measures (populations, landscapes, times and scales…), the search by the analysts becomes one of identifying specific, localized or idiographic factors at work. What you are studying may be non-generalizable–that is, it may be a case it its own right–and failing to triangulate is one way to help confirm that.

3. Methodologically, analogies without counter-cases are empty signifiers

The relentless rise of modern inequality is widely appreciated to have taken on crisis dimensions, and in moments of crisis, the public, politicians and academics alike look to historical analogies for guidance.

Trevor Jackson (2023). “The new history of old inequality.” Past & Present, 259(1): 262–289 (https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtac009)

I

I bolded the preceding because its insight is major: The search for analogies from the past for the present is especially acute in turbulent times.

The methodological problem–which is also a matter of historical record–is any misleading analogy. Jackson, by way of illustrating this point, provides ample evidence to question the commonplace that the US is presently in “the Second (New) Gilded Age,” with rising inequality, populism and corruption last seen in the final quarter of our 19th century.

II

But we are still stuck with the fallacy of composition. Not all of the country was going through the Gilded Age, even when underway. And doubtless parts of the country are now going through a Second Gilded Age, even if not nationally.

The upshot is that we must press the advocates of this or that analogy to go further. The burden of proof is on the advocates to demonstrate their generalizations hold regardless of the more granular exceptions, including those reframed by other analogies.

Why would they concede exceptions? Because we, their interlocutors, know empirically that micro and macro can be loosely-coupled, and most certainly not as tightly coupled as theory and ideology often have it. Broad analogies that do not admit granular counter-cases float unhelpfully above policy and management.

A fairly uncontroversial upshot, I should have thought, but let’s make the matter harder for us.

III

The same day I read Jackson’s article, I can across the following analogy for current events. Asked if there were any parallels to the Roman Empire, Edward Luttwak, a scholar on international, military and grand strategy, offered this:

Well, here is one parallel: after 378 years of success, Rome, which was surrounded by barbarians, slowly started admitting them until it completely changed society and the whole thing collapsed. I am sure you know that the so-called barbarian invasions were, in fact, illegal migrations. These barbarians were pressing against the border. They wanted to come into the Empire because the Romans had facilities like roads and waterworks. They knew that life in the Roman Empire was great. Some of these barbarians were “asylum seekers,” like the Goths who crossed the Danube while fleeing the Huns.

https://im1776.com/2023/10/04/edward-luttwak-interview/?ref=thebrowser.com&utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

Of course, some read this as inflammatory and go no further. Others, of course, dismiss this outright as racist, adding the ad hominem “Just look at who is writing and publishes this stuff!”

But the method to adopt would be to press Luttwak for definitions and, most importantly, counter-examples.

4. Peer review: another area where error avoidance is the method for reliability management

Below is part of an interchange in the Comments section of a recent Financial Times article on scientific fraud:

Comment: I am a scientist. I spend all my time trying not to be wrong in print. Even then, occasionally I am. It is the same for all of us. Furthermore, some scientists are very poor at dealing with statistics and are thus wrong more than others. Our common incompetence is different from actual fraud. The proportion of frauds has probably held steady since the time science became a profession and has grown as the number of scientists has grown. I find it unlikely that the proportion of scientists with this character flaw has increased recently. Possibly much more common than fraud is ripping off your collaborators, or stealing ideas during reviews of manuscripts and grant applications. That is quite hard to prove and so it seems to be popular among certain character types but again, there is no reason to think their proportion has increased.

Reply: It actually doesn’t matter if the proportion is remaining steady – even though it almost certainly is growing, with so much more financial, career and political pressure on academics these days, and a for-profit publishing system that reduces public oversight and is massively biased towards positive outcomes.

The goal should remain zero.

It’s unacceptable for scientists to publish errors due to being ‘poor at statistics’. Huge amounts of money is being wasted, lives are being lost – the least people can do is get training, or work with someone else who IS good at them.

https://www.ft.com/content/c88634cd-ea99-41ec-8422-b47ed2ffc45a

Upshot: If peer review isn’t solely about error avoidance, how can it aspire to be reliable?

5. Not all the “can’s, might’s, may’s, or could’s” add up to one single “must” in policy analysis

Consider the following example (my bolding):

Our expert-interview exercise with leading thinkers on the topic revealed how climate technologies can potentially propagate very different types of conflict at different scales and among diverse political actors. Conflict and war could be pursued intentionally (direct targeted deployment, especially weather-modification efforts targeting key resources such as fishing, agriculture, or forests) or result accidently (unintended collateral damage during existing conflicts or even owing to miscalculation). Conflict could be over material resources (mines or technology supply chains) or even immaterial resources (patents, software, control systems prone to hacking). The protagonists of conflict could be unilateral (a state, a populist leader, a billionaire) or multi- lateral in nature (via cartels and clubs, a new “Green OPEC”). Research and deployment could exacerbate ongoing instability and conflict, or cause and contribute to entirely new conflicts. Militarization could be over perceptions of unauthorized or destabilizing deployment (India worrying that China has utilized it to affect the monsoon cycle), or to enforce deployment or deter noncompliance (militaries sent in to protect carbon reservoirs or large-scale afforestation or ecosystem projects). Conflict potential could involve a catastrophic, one-off event such as a great power war or nuclear war, or instead a more chronic and recurring series of events, such as heightening tensions in the global political system to the point of miscalculation, counter-geoengineering, permissive tolerance and brinksmanship. . . .

States and actors will need to proceed even more cautiously in the future if they are to avoid making these predictions into reality, and more effective governance architectures may be warranted to constrain rather than enable deployment, particularly in cases that might lead to spiralling, retaliatory developments toward greater conflict. After all, to address the wicked problem of climate change while creating more pernicious political problems that damage our collective security is a future we must avoid.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211467X22002255 (my bolds)

Let’s be clear: All such “could’s-as-possibilities” do not add up to one single “must-as-necessity.”

The only way in this particular passage that “could” and “can” link to “must” would mean that the article–and like ones–began with “We must avoid this or that” and then proceeded to demonstrate how to undertake really-existing error avoidance with respect to those could-events and might-be’s.

6. But in policy advocacy, conditions of “could and might” do lead to proposals that “require and would”

I just read an article [1] that demonstrated how the climate and capitalism crises need to be analyzed together in order to better address how emotions such as anxiety and burnout with respect to each crisis are highly interconnected.

I agree. But I worry how readers might conflate advocacy and analysis.

I agree with the author that so much could help improve the situation: “these insights could be deepened by placing them in the context of the care crisis of neoliberal capitalism”; “such reforms could help create the preconditions for deeper post-capitalist transformation”; and “a ‘polycrisis’ lens might usefully decenter the climate crisis while informing a broader analytic framework and political program”.

But then the author asserts that “this must be a form of polycrisis analysis deeply influenced by Feminist and ecological Marxism”. Also, some could-reforms “must prioritize public transit over private cars, circular economies, and extended producer responsibility to reduce extraction as far as possible”. Indeed and also specifically [my bolding below]:

To a large extent this requires the decommodification of care, involving ‘universal guarantees in place that all people will be entitled to care,’ along with expanding publicly funded childcare, physical and mental healthcare, elderly care, and care for those with disabilities (ibid: 195–196). It also requires revitalizing community infrastructures – like libraries, community centers, parks, and public spaces – that have decayed under decades of neoliberal privatization and austerity (particularly in poor communities) (Rose 2020). More broadly, ending the care crisis requires social programs that dramatically reduce (if not eliminate) the emotionally distressing dynamics of debt and unemployment by improving economic security for all.

I have no problem with these requirements! My problem is with the paradox: Conditions are sufficiently uncertain that we cannot say the proposed reforms would actually work, but we are certain enough to say that these proposed reforms entail must-requirements of varying degrees of specificity.

Now there is nothing “illogical” about taking that latter position. It’s what we expect from policy advocacy. This is what policy advocates do; theirs is not to analyze the uncertainties and certainties case-by-case; that’s my job as a practicing policy analyst. Policy analysts of course make recommendations and that is an advocacy of sorts. But they do so in the face of that case-specific determination of what is “sufficiently certain” and “certain enough.” For advocates, the determination is a settled method over the range of cases.

[1] Michael J. Albert (2025). “It’s not just climate: rethinking ‘climate emotions’ in the age of burnout capitalism. Environmental Politics (accessed online at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09644016.2025.2526228).

7. To paraphrase Wittgenstein, methodologically an infinite regress explains nothing

Stop fossil fuels; stop cutting down trees; stop using plastics; stop this defense spending; stop being imperialist; stop techno-solutionism; be small-d democratic and small-p participatory; dismantle capitalism, racism and the rest; transform cities; save biodiversity; never forget class, gender, race, inequality, religions, bad faith, identity. . .and. . .and. . .

8. The Achilles heel of conventional risk management methods is the counterfactual

I

For me, the crux of counterfactual history is a present always not one way only. You want a counterfactual, but for which current interpretation or set of historical interpretations?

What’s at work are the two blades of a scissors. One devotes time and attention to “what is happening,” a state of affairs that can be interpreted in multiple different ways. The other devotes time and attention to “what has happened,” a state of affairs that could have turned out differently and so too the allied interpretations.

Where the blades slice, they open up not only the contingent nature of events past and present, but also the recasting of what is and has been.

II

For example, consider a city’s building code. Viewed one way, it is sequential interconnectivity (do this-now followed by do-that-then). But if cities also view their building codes as the means to bring structures up to or better than current seismic standards, then the code becomes a focal mechanism for pooled interconnectivity among these developers and builders.

That neither is guaranteed should be obvious. That you in no way need recourse to the language of conventional risk management to conclude so should also be obvious.

9. What “calling for increased granularity” means

I

When I say concepts like regulation, inequality, and poverty are too abstract, I am not criticizing abstraction. I am saying (1) that these concepts are not differentiated enough for an actionable policy or management and (2) that this actionable granularity requires a particular kind abstraction from the get-go.

What then does “actionable granularity” mean?

II

I have in mind the range of policy analysis and management that exists between, on the one side, the adaptation of policy and management designs and principles to local circumstances and, on the other side, the recognition that systemwide patterns emerging across a diverse set of existing cases inevitably contrast with official and context-specific policy and management designs.

Think here of adapting your systemwide definition of poverty to local contingencies and having to accommodate the fact that patterns that emerge across how really-existing people identify poverty differ from not only system definitions but also from localized poverty scenarios based in these definitions.

III

One implication is that cases that are not framed by emerging patterns and, on the other side, by localized design scenarios are rightfully called “unique.” Unique cases of poverty cannot be abstracted, just as some concepts of poverty are, in my view, too abstract. Unique cases stand outside the actionable granularity of interest here for policy and management.

Where so, there is the methodological problem of cases that are assumed to be unique or stand-alone, when in fact no prior effort has been made to ascertain (1) systemwide patterns and local contingency scenarios in which the case might be embedded along with (2) the practices, if any, of adaptation and modification that emerge as a result.

From a policy and management perspective, such cases have been prematurely rendered unique: They have been, if you will, over-complexified so as to permit no abstraction. Unique cases are not themselves something we can even abstract as sui generis or “‘a case’ in its own right.”

I stress this point if only because of the exceptionalism deferred to “wicked policy problems”. Where the methodological problem of premature complexification isn’t addressed beforehand, then by definition the so-called wicked policy problem is prematurely “wickedly unique.” Or, more ironically, uniquely wicked problems are abstracted insufficiently for the purposes of systemwide pattern recognition and design scenario modification.

10. The methodological relevance of like-to-like comparisons for policy and management

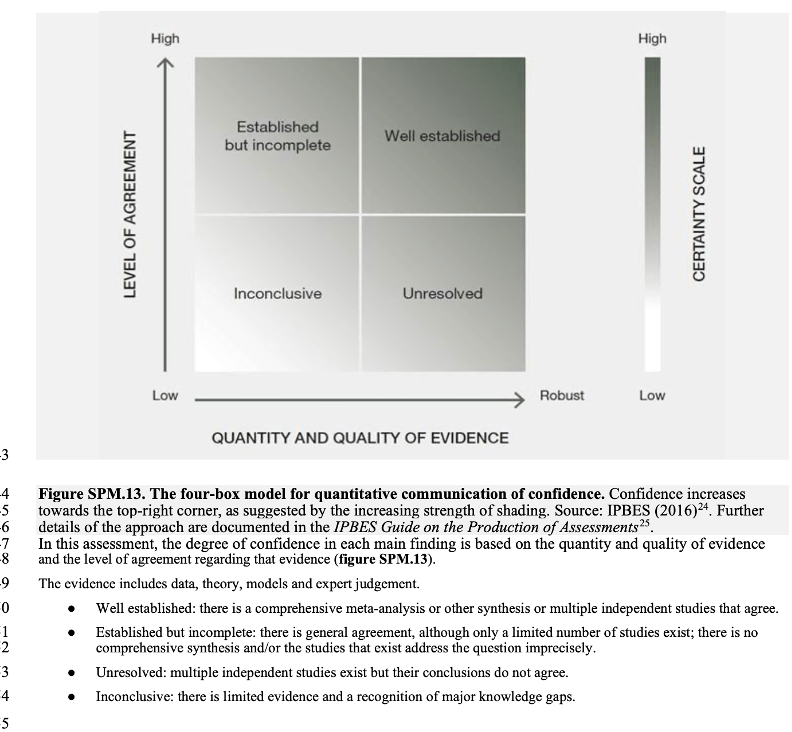

Assume the following typology, a 2 X 2 table identifying four types of confidence you have over empirical findings for policy analysis and policymaking:

Even with all that detail, it’s fairly easy to critique the above. Do we really believe, for example, that well-established evidence and high certainty are as tightly coupled and correlated? In fact, each dimension can be problematize in ways relevant to policy analysis and policymaking.

But the methodological issue at stake here is to compare like to like.

That is, interrogate the cells of the above typology using the cells of another typology whose overlapping dimensions also problematize those of the above. Consider, for example, the Thompson-Tuden typology, where the key decisionmaking process is a function of agreement (or lack thereof) over policy-relevant means and ends:

This latter typology has a few surprises for the former one. Contrary to the notion that inconclusive evidence is “solved” by more and better evidence, the persistence of “inconclusive” (because, say, of increasing urgency and interruptions) implies eventually lapsing, it is hypothesized, into decisionmaking-by-inspiration. So too the persistence of “unresolved” or “established but incomplete” shuttles, again and again, between decisionmaking by majority-rule and by compromises. More, what is tightly coupled in the latter isn’t “evidence and certainty” as in the former, but rather the beliefs over evidence with respect to causation and the preferences for agreed-upon ends and goals.

In case it needs saying, methodological like-to-like comparisons of typologies need not stop at a comparison of two only. Social and organizational complexity means the more typologies the better by way of finding something more tractable to policy or management.

11. The methodological importance of “and-yet” counternarratives

The paragraph I’ve just read before typing this is bookended by two quotes:

Just before: “Therefore, rather than being schools of democracy, ACs [associative councils] may be spaces where associative and political elites interact and, therefore, just reproduce existing political inequities (Navarro, 2000). Furthermore, these institutions may have limited impact in growing and diversifying the body of citizens making contributions to public debate (Fraser, 1990).”

Just after: “The professionalised model results from a complex combination of inequalities in associationism and a specific type of participation labour. Analysing the qualitative interviews, regulations and documents was fundamental to understanding the underlying logic of selecting professionals as the main components.”

Now try to guess the gist of the paragraph in between. More of the same? Well, no. Six paragraphs from the article’s end emerges an “and-yet” that had been there from the beginning of the article:

Nevertheless, an alternative interpretation of professionalisation should be considered. The fact that ACs perform so poorly in inclusiveness does not mean that they are not valuable for other purposes, such as voicing a plurality of interests in policymaking (Cohen, 2009). In this respect, participants can act as representatives of associations that, in many cases, promote the needs of oppressed and exploited groups (De Graaf et al., 2015; Wampler, 2007). Suffice it to say, for example, that labour unions or migrants’ associations frequently send lawyers or social workers to ACs to defend their needs and positions. Problems with inclusion should not take away from other purposes, that is, struggles to introduce critical issues and redistribution demands to the state agenda. Other studies have already shown that groups make strategic decisions to achieve better negotiation outcomes in the context of technical debates (Grillos, 2022). Thus, the choice of selecting professionals can be a strategy to improve the capacity of pressure in institutional spaces dominated by experts. (my bold; accessed online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00323217251319065)

Methodological upshot: What the counterfactual is to economic analysis, the and-yet counternarratives are to policy analysis.

12. The cross-cutting methodological fault-line in Infrastructure Studies, and why it matters

The large-scale infrastructure is never safe from the disciplinary and interdisciplinary assaults of economists, civil engineers, ecologists, risk managers, political scientists, anthropologists and so many more, each claiming a special purchase that demands our attention. A less banal observation is the cross-cutting methodological default line once each discipline’s poses its “big picture”: Some ratchet up further analysis to the global, while others dig down into the granular. We’re told that further analysis necessarily entails resorting to understanding the wider contexts (political, social, cultural. . .) or the more fine-grained practices, processes and interactions.

For example, we’re told that the study of digital archives is first and foremost “deeply rooted in the history of infrastructure policy”. But you have a choice in describing that “policy:” ratcheting up or digging down. So often today the road taken is the former:

In our attempt to understand contemporary archival politics, it would seem much more beneficial to pay attention to the concrete political issues in which community digital archives are involved, such as, for example, armed conflict and civil unrest (e.g. The Mosireen Collective 2024; Syrian Archive 2024; Ukraine War Archive 2024), gender queerness (e.g. Australian Queer Archives 2024; Digitial Transgender Archive 2024; Queer Digital History Project 2024), forced migration (e.g. The Amplification Project 2024; Archivio Memorie Migranti 2024; Living Refugee Archive 2024), post-colonialism (e.g. Talking Objects Lab 2024), rights of Indigenous peoples (e.g. Archivo Digital Indigena 2024; Digital Sami Archives 2024; Mukurtu 2024), racial discrimination (e.g. The Black Archives 2024; Black Digital Archiving 2024), or feminism (e.g. Féminicides (2024); Feminist Archive North 2024, Rise Up 2024).

You many wonder at the methodological finesse taking place in this passage, namely: equating the concrete with the abstract. This transmutation is made easier because it is not really-existing archival practices that the author describes, but rather “the politics of digital archival practice.” Rather than being case-specific, these politics face outward and upward. They’re “political agendas,” not micro-practices. Such is why the author can write he is “attending to the politics of digital archives at the level of concrete archival practices,” while in no way differentiating concrete practices, processes and interactions of each of the bolded categories and how they work themselves out relationally, case by case and over time.

Lesson? Just say you’re talking about politics and you’re taken to be more practical than practical?

I however come from profession, policy analysis, whose propensity is to dig down rather than ratchets up analysis, especially when it comes Infrastructure Studies. The “big picture” each discipline gives us is too important in terms of policy relevance for them alone to determine how to move the analysis forward. To equate policy with politics is to miss practices, processes and interactions that matter.

In the infrastructure case of digital archives, I suspend judgment over the author’s conclusion precisely because no concrete practices of digital archiving are detailed over a range of different cases. Please note: He may well have them at hand and to be clear, I am happy to search out practices that float something in and through passages such as:

Similarly, the temporality of community-based digital archival enterprises seems neither ephemeral nor unfathomable. Rather, it plays a crucial role in rearticulating the historical subjectivities of various Queer, Indigenous, post-colonial, and other marginalized communities. And indeed, such enterprises and the rise of participatory and collaborative archiving can surely also be seen as examples of ‘collectivization’ and ‘socialization’ or even of ‘the dialectics between the individual and the society’–the very conditions of politics and historicity that Étienne Balibar (2024) sees ‘the digital’ as precluding.

Source.

Goran Gaber (2025): “Mind the Gap. On archival politics and historical theory in the digital age,” Rethinking History, (accessed online at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13642529.2025.2545029)

13. Seven differences in method that matter for reliable policy and management

When I and others call for better recognition and accommodation of complexity, we mean the complex as well as the uncertain, unfinished and conflicted must be particularized and contextualized so that we can analyze and manage, if only case-by-granular case.

When I and others say we need more findings that can be replicated across a range of cases, we are calling for identifying not only emerging better practices across cases, but also greater equifinality: finding multiple but different pathways to achieve similar objectives, given case diversity.

What I and others mean by calling for greater collaboration is not just more teamwork or working with more and different stakeholders, but that team members and stakeholders “bring the system into the room” for the purposes of making the services in question reliable and safe.

When I and others call for more system integration, we mean the need to recouple the decoupled activities in ways that better mimic but can never fully reproduce the coupled nature of the wider system environment.

When I and others call for more flexibility, we mean the need for greater maneuverability across different performance modes in the face of changing system volatility and options to respond to those changes. (“Only the middle road does not lead to Rome,” said composer, Arnold Schoenberg.)

Where we need more experimentation, we do not mean more trial-and-error learning, when the systemwide error ends up being the last systemwide trial by destroying the limits of survival.

While others talk about risks in a system’s hazardous components, we point to different systemwide reliability standards and then, to the different risks and uncertainties that follow from different standards.

11 thoughts on “Major Read: New method matters in reframing policy and management (13 examples)”