Edited from: E. Roe (2007). Narrative Policy Analysis for Decision Making. In: Goktug Morcel, Ed. (2007). Handbook of Decision Making. CRC Taylor and Francis, Boca Raton: 607 – 626. An epilogue updates points about the metanarrative(s).

THE PROBLEM OF EVALUATION

As originally conceived in Narrative Policy Analysis (Roe, 1994), determination of what was the better policy narrative took place around three connected features. The preferred narrative was one (1) that took seriously the fact that development is genuinely complex, uncertain, unfinished and conflicted, (2) that moved beyond critique of other narratives, and (3) that told a better story, i.e., a more comprehensive yet parsimonious account that did not dismiss or deny the issue’s contraries but which was amenable to policymaking and management.

Narratives for and against globalization provide an example of the strengths and limitations in this initial approach.

GLOBALIZATION

Readers scarcely need be told that the policy narrative in favor of the economic globalization of trade was a dominant scenario in numerous decision making arenas, as witnessed by the many calls for trade liberalization as a way of expanding economic growth. There have always been various counternarratives (counter-scenarios or counter-arguments) to globalization scenarios. For our purposes, focus on the opposing arguments to globalization put forth by environmental proponents of sustainable development. This early opposition can be roughly divided into two camps: a “green” counternarrative and an “ecological” one (Roe & Van Eeten, 2004).

The green counternarrative assumes that we have already witnessed sufficient harm to the environment due to globalization and thus demands taking action now to restrain further globalizing forces. It is confident in its knowledge about the causes of environmental degradation as they relate to globalization and certain in its opposition to globalization. In contrast, the ecological counternarrative starts with the potentially massive but largely unknown effects of globalization on the environment that have been largely identified by ecologists. Here enormous uncertainties over the impacts of globalization, some of which could well be irreversible, are reason enough not to promote or tolerate further globalization.

Where the green counternarrative looks at the planet and sees global certainties and destructive processes definitively at work, those ecologists and others who subscribe to the ecological counternarrative know that ecosystems are extremely complex, and thus the planet must be the most causally complex ecosystem there is. The ecological counternarrative opposes globalization because of what is not known, while the green counternarrative opposes globalization because of what is known. The former calls for more research and study and invokes the precautionary principle—do nothing unless you can demonstrate it will do no harm. The latter says we do not need more research or studies in order to do something—take action now—precisely because we have seen and continue to see the harm.

Neither the green nor the ecological counternarrative meets fully all three features for a better narrative, however.

Clearly, the ecological counternarrative is preferable over the green version in terms of the first feature. The ecological counternarrative takes uncertainty and complexity seriously throughout, while its green counterpart goes out of its way to deny that any major dispositive uncertainties and complexities are at work. Does this then mean the ecological version is the better environmental counternarrative? The answer depends on the other two criteria, and here problems arise. Plainly, the ecological counternarrative is open to all manner of critique, if simply because of its reliance on the precautionary principle, e.g., I can no more prove a negative than I can show beforehand that application of the precautionary principle itself will do no harm in the future (see Duvick, 1999). That said, from the narrative policy analysis framework, critiques against the precautionary principle or for that matter against the ecological counternarrative are of little decision making use if they are not accompanied by alternative formulations that better explain how and why it makes sense to be environmentally opposed to globalization.

What about the third criterion? Is there at least one metanarrative that explains how it is possible to hold, at the same time and without being incoherent or inconsistent, the dominant policy narrative about globalization, its counternarratives, and other accounts, including critiques of the former? Readers may have different metanarratives in mind, but the one I am most familiar with is the metanarrative about who claims to have the best right to steward the planet. The proponents of globalization and the proponents of the counternarrativez disagree over what is best for the environment, but both groups are part and parcel of the same techno-managerial elite who claim they know what is best for us.

According to this metanarrative, we need free trade or the precautionary principle or whatever because we—the unwashed majority—cannot better steward our resources on our own. While we may bristle against the elite condescension—who elected them?—it is patent that the metanarrative does not take us very far in deciding what to do next and instead. We are still left with the question: What is the better policy (meta)narrative?

Fortunately, it is now possible to provide a fuller evaluative framework of policy narratives. We know more than we did in the early 1990s about what it takes to ensure reliable development services taken to be critical by the human populations concerned, and in that knowledge can be found the better policy narratives. As one might expect, the evaluation is contingent on who is doing the evaluating (and their own definitions even if not operationalized in social science terms).

FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING POLICY NARRATIVES

Assume any system—technical, agricultural, social, ecological or the one you have in mind now—has as a priority the aim of providing reliable critical services. It may not be the only aim, but it is a priority. The critical services may be crops, water, transportation, or electricity, among others. “Reliable” means the critical services are provided safely and continuously even during peak demand periods. The lights stay on, even when generators could do with maintenance; crop production varies seasonally, but food supplies remain stable; and we have clean water because we have managed our livestock so as not to harm the aquifer. The challenge to maintain reliable services is daunting, as these critical service systems—technical, agricultural, social, and ecological—can be tightly coupled and complexly interactive. The generator goes off, and the knock-on, cascading effects might be dramatic.

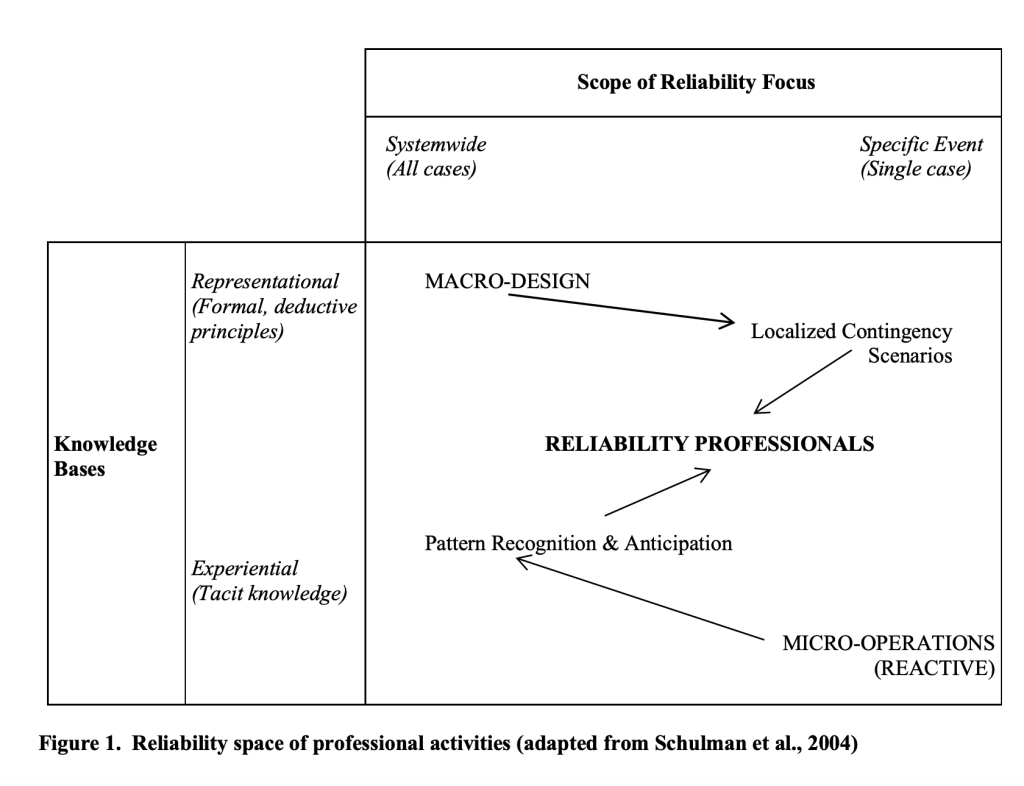

The wider literature my colleagues and I have been contributing to (Schulman, Roe, van Eeten, and de Bruijne, 2004; Roe, van Eeten, Schulman, & de Bruijne, 2002; Roe, Schulman, van Eeten & de Bruijne, 2005; see also Roe, 2004) tells us that the drive to high reliability management in such systems can be described along two dimensions:[1] (1) the type of knowledge brought to bear on efforts to make the system reliable, and (2) the focus of attention or scope of those reliability efforts. The knowledge bases from which reliable performance is pursued can range from formal or representational knowledge, in which key efforts are understood through abstract principles and deductive models based upon the principles, to experience, based on informal, tacit understanding. Knowledge bases, in brief, vary in their mix of induction and deduction, and thus their assembly of differing arguments and scenarios into policy narratives.

At the same time, the scope of attention can range from a purview which embraces reliability as an entire system output, encompassing many variables and elements, to a case-by-case focus in which each case is viewed as a particular event with distinct properties or features. Typically, scope is articulated in policy narratives as the different scales, ranging from specific to general, that must be taken into account. The two continua of knowledge and scope define a conceptual and perceptual space (Figure 1), where high reliability can be pursued (defined again as the continuous and safe provision of the critical service even during periods of stress). Four nodes of activities and the domain of the reliability professional are identified:

At the extreme of both scope and formal principles is the macro-design approach to reliable critical services (the “macro-design node”). Here formal deductive principles are applied at the systemwide level to understand a wide variety of critical processes. It is considered inappropriate to operate beyond the design analysis, and analysis is meant to cover an entire system, including every last case to which that system can be subjected. At the other extreme is the activity of the continually reactive behavior in the face of real-time challenges at the micro-level (the “micro-operations” node). Here reliability resides in the reaction time of the system operators working at the event level rather than the anticipation of system designers for whatever eventuality. The experiences of crisis managers and emergency responders are exemplary.

But designers cannot foresee everything, and the more “complete” a logic of design principles attempts to be, the more likely it is that the full set will contain two or more principles contradicting each other (again, prove beforehand that application of the precautionary principle will itself do no harm). On the other hand, operator reactions by their very nature are likely to give the operator too specific and hasty a picture, losing sight of the forest for the trees in front of the manager or operator. Micro-experience can become a “trained incapacity” that leads to actions undermining reliability, as the persons concerned may well not be aware of the wider ramifications of their behavior.

What to do then, if the aim is system reliability? Clearly, “moving horizontally” across the reliability space directly from one corner across to the opposite corner is unlikely to be successful. A great deal of our research has found that attempts to impose large-scale formal designs directly onto an individual case—to attempt to anticipate and fully deduce and determine the behavior of each instance from systemwide principles alone—are very risky when not outright fallacious (variously called the fallacy of composition in logic or the ecological fallacy in sociology). That said, reactive operations by the individual hardly constitute a template for scaling up to the system, as management fads demonstrate continually.

Instead of horizontal, corner-to-corner movements, Figure 1 indicates that reliability is enhanced when shifts in scope are accompanied by shifts in the knowledge bases. To be highly reliable requires more and different knowledge than found at the extremes of a priori principles and phenomenological experience. We know from our research that reliability is enhanced when designers apply their designs less globally and relax their commitment to a set of principles that fully determine system operations. This happens when designers embrace a wider set of contingencies in their analyses and entertain alternate, more localized (including regional) scenarios for system behavior and performance (the “localized contingent scenarios node” in Figure 1). From the other direction, reactive operations can shift away from real-time firefighting toward recognizing and anticipating patterns across a run of real-time cases (the “pattern recognition and anticipation node”). Operator and managerial adaptation—recognizing common patterns and anticipating strategies to cover similar categories of micro events or cases—arises. These emerging norms, strategies and routines are likely to be less formal than the protocols developed through contingency analysis or scenario-building.

It is in this middle ground where worldviews are tempered by individual experience, where discretion and improvisation probe design, where anticipated patterns mesh with localized scenarios, and where shared views are reconciled with individualized perspectives. Our research tells us that sustaining critical services in a reliable fashion is not really possible until the knowledge bases have shifted from what is known at the macro, micro, localized scenario and pattern recognition levels. The four nodes are important only to the extent that designs, scenarios, personal experience and empirical generalization can be translated into reliable critical services across the scales of interest. The translation is interpretative rather than literal—that is why new or different knowledge is generated.

The middle ground is, in our phrase, the domain of the reliability professional. These are the people who excel at cross-scale, context-dependent case-by-case analysis. They are the middle level managers and operators in the control rooms of our technical systems; they are the medical staff in our hospital emergency rooms; they are the firefighters who know when to drop their shovels and run for it; they are the farmers who decide to plow now before the first rains, the pastoralists who move their herds only now after the first rains, the experienced extension agent and researcher who does not turn away from the villager they have worked with the minute she asks, “But what do we do now….” They excel at formulating and evaluating what-if scenarios in order to answer: What do we do next? (The inability to answer “what happens next, according to the narrative of interest?” remains a shortcoming attributed to other approaches to discourse and narrative analyses.)

AN EXAMPLE IN APPLYING THE FRAMEWORK FOR EVALUATING POLICY NARRATIVES

As we shall see, the policy narratives deployed by reliability professionals are different than those found populating the four nodes of macro-design, localized contingency scenarios, pattern recognition and anticipation, and micro-operations in much of the published literature. This is to be expected since the knowledge bases used in the narratives are different. Reliability professionals and the arguments they make have of course always been there, decade after decade. To be thoroughly arbitrary, we read about them in Albert Hirschman’s Development Projects Observed (1967), Robert Chambers’ Managing Rural Development (1974), and Jon Moris’s implementation-oriented Managing Induced Rural Development (1981)—and that only touches the tip of a literature on reliability professionals in development. Hindsight, a facility for other languages, and greater respect for the fugitive literature would easily chronicle other archaeologies.

What has changed since the 1990s is that the reliability space and the differences in policy narratives around the nodes and in the middle are more obvious than before in a number of cases. One example will have to suffice.

The Science of Sustainable Development, by Jeff Sayer and Bruce Campbell (2004), has plainly been written by and for the reliability professionals working in the middle of the development and the environment arena. The book, authored by two development practitioners with strong research and administrative bona fides, sought to demonstrate how integrated natural resource management happens in practice at the time of writing. Through case studies from Borneo, Zimbabwe, and the Ecuadorian Andes and a very broad synthesis of the literature, the book “aims to demystify the sometimes obscure science of natural resources management, interpreting it for the benefit of those who need to deal with the day-to-day problems of managing complex natural resources” (p. i). That word, “interpreting,” is more path-breaking than one first notice, because it is directly tied to the translation function that reliability professionals provide. In this way, the book reflected a major shift that was taking place over the years away from conventional development and environment narratives based solely or primarily on designs.

It is important to underscore how different the Sayer and Campbell discussion of “sustainable development” is from that which still takes place at the four nodes. It would be easy enough to critique their book from the nodes looking into the domain the authors occupy. One can already hear the critics. From the macro-design node: “But the book doesn’t have a chapter on the foundations and principles of sustainable development. . .” From the local scenario node: “But the book doesn’t have any discussion on the model that hunter-gatherers offer for contemporary sustainable development…” From the micro-experience node: “But the book doesn’t tell us what the lived daily experience is really like for a peasant under ‘sustainable development’…” From the pattern recognition node: “But the book has no discussion of global trends in per capita consumption and population growth rates that affect sustainable development…”

The point is not that these narratives from the outside are irrelevant. On the contrary, they could be very important—if and when they can be translated and interpreted into the different knowledge bases required for sustainable (a.k.a., reliable) development across multiple scales from the global to the specific. For example, the book is mercifully free of the de rigueur macro-narrative about sustainable development as managing resources today so that the future has a chance to manage them tomorrow. It is not that the Bruntland Commission definition is “wrong,” but that it never has been specific enough for management purposes. For Sayer and Campbell (2004, p. 57) as well as many others (this author included), the better narrative—that is, one which interprets Bruntland in reliability terms—is: Sustainable development is about creating human opportunities to respond to unpredictable change across the scales humans find themselves interacting without killing life in the process. That narrative is difficult enough to realize, but at least unpredictability and uncontrollability move center stage where they must be if sustainability is to be taken seriously.

Sayer and Campbell write decidedly from within the reliability space looking out to the nodes beyond. The two authors make it patent that sustainable livelihoods will not be possible until new and different knowledge bases are brought to bear across the scales from case to system. (In fact, one cannot talk about multiple scales for sustainability without shifting from knowledge bases.) The authors’ call for more participatory action research (PAR), scaling out (rather than up or down), and use of “throwaway” models is especially apposite because those approaches at best help information gatherers become information users. At worst, PAR and formal models can be made as formulaic as the project log frame at the macro-design node, as the authors are quick to point out.

Sayer and Campbell’s call for more science-based integrated resource management can also be understood in the same light. When “Science” comes to us in a capital-S—a set of must-do’s (e.g., random assignment groups and controls)—it is too rigid for ready translation by reliability professionals working in the middle. Yet Sayer and Campbell are correct to insist that small-s science has a major contribution to make. Science when understood as one way to tack from the four nodes to the middle—that is, to make sense of principles, scenarios, the ideographic, and livelihood patterns—is crucial.

The implication for evaluating policy narratives is as dramatic as it is straightforward. In terms of the above framework, the more useful way to evaluate the narratives in Sayer and Campbell’s The Science of Sustainable Development is not from the outside looking in, but from the inside looking out along with other reliability professionals.

What precisely are the policy narratives deployed by reliability professionals such as Sayer and Campbell? They are not alone among development practitioners in making much of the importance of complexity and uncertainty, flexibility, experimentation, replication, integration, risk, learning, adaptive management and collaboration to the work of development. The terms and the narratives they reflect are very much the common currency of many writing from the middle. When narrativized, however, the terms can render the insights from the middle banal to even the 17-year old undergraduate—“Take uncertainty into account” Awesome! “You must be flexible in your approach” Too right!

In actuality, once the terms are probed further, they retain their unique insights. Again, we are in the presence of few studies but a great deal of practice. When reliability professionals say we need more learning, what they are often talking about is a very special kind of learning from samples of one case or fewer, as from simulations (see March, Sproul & Tamuz, 1991). When they say we must recognize and accommodate complexity and uncertainty, what mean this amalgam of the uncertain, complex, unfinished and conflicted must be particularized and contextualized if we are to analyze and manage natural resources case by case (Roe, 1998). When they say we need more findings and better science that can be replicated across a wide variety of cases, what they really are calling for is identifying greater equifinality in results, that is, finding multiple but different pathways to achieve the similar objectives, given the variety of cases (cf. Belovsky, Botkin, Crowl, Cummins, Franklin, Hunter, Joern, Lindenmayer, MacMahon, Margules, & Scott, 2004).

What reliability professionals mean by calling for greater collaboration is not just more team work or working with more stakeholders, but rather that the team members and stakeholders “bring the whole system into the room” for the purposes of rendering the services in question reliable (see Weisbord & Janoff, 1995). When they talk about the need for more integration, what they really mean is the need to recouple what have been all too decoupled and fragmented development activities in ways that better mimic but can never fully reflect the coupled nature of the environment around them (Van Eeten & Roe, 2002). When they call for more flexibility, what they mean is the need for greater maneuverability of the reliability professionals in the face of changing system volatility and options to respond to those changes (Roe et al, 2002).

If reliability professionals say we need more experimentation, they decidedly do not mean more trial and error learning, when survival demands that the first error never be the last trial (see Rochlin, 1993). So when they call for more adaptive management, what they often are asking for is greater case-by-case discriminations in management alternatives, depending on the particulars (Roe & Van Eeten, 2001a). In this and the other ways, activities in the middle domain have not become “more certain and less complex,” but rather that the operating uncertainties and complexities have changed with the knowledge bases. Policy narratives remain needed, but they are decidedly different than those claiming priority at and around the four outer nodes.

If we fully appreciated the differences, longstanding development controversies, such as that of “planning versus implementation,” would have to be substantially recast. If you look closely at Figure 1, you see we are talking about professionals who are expert not because they “bridge” macro-planning and micro-implementation, but because they are able to translate that planning and implementation into the reliable critical services.

CONCLUSION

Just because they are all narratives does not mean that all policy narratives are equal. Just because policy narratives can be found doing battle with each other and across the nodes does not mean that the stakes are higher there. Nor does it mean these nodal narratives are the better ones because the shouting and waving is more frantic there, at least when it comes to underwriting and stabilizing decision making over critical services whose reliability matters to society and the public.

Readers must not be too sanguine that those at the nodes will take account of those in the middle domain. No matter what professionals such as Sayer and Campbell (2004) or all the other reliability practitioners have to say, there will be the economist who all but pats us on the head, saying, “Well, obviously the prices aren’t right.” Or the regional specialist who sighs, “Obviously, it’s because. . .well, it’s Africa. . .” Or the ethnographer who counters, “You don’t know what these villagers are telling me!” Or the numbers expert who says, “Nor do you know the latest trends.” To adapt the useful phrase of Robert Chambers (1988), “normal professionalism” has all but been equated with those who claim to speak for and hold expertise at the four nodes.

The fact of the matter is that we have very little research on reliability professionals and more than ample study of the nodes. Almost all the airtime in “doing development” has been given to the short-cut metaphysics of dominant policy narratives. If only we had full cost pricing, or sufficient political will, or had publics that could solve Arrow’s voting paradox on their own, then everything would be okay. We can, they promise, jump from macro to micro and back again when it comes to ensuring reliability. In contrast, the middle is very much terra incognita if only because it has no real value to those who already know, after a fashion, the Answer. Reliability professionals—be they villagers or control room operators—are very much the marginalized voices to whom Narrative Policy Analysis recommended we give more attention.

To get to the middle is daunting, but far too many of our long-lived debates have been at the extremes of the reliability space, haven’t they? Planning versus Markets. Markets versus Hierarchy. Science versus Technology versus Politics. Which way Africa: Kenyatta or Nyerere? Which way Latin America: Structural Adjustment or Basic Human Needs? Which way the world: Globalization or Anti-Globalization? We might as well be talking about who is more likely to be in Heaven, Plato or Aristotle.

EPILOGUE (OCTOBER 2025)

Since the publication of the Handbook chapter from which the above has been excerpted, more research has been undertaken on high reliability management by reliability professionals in the context of interconnected critical infrastructures (Roe and Schulman 2008, 2016, 2018, 2023).

It is clearer now that the centralized control room in a critical infrastructure (and not all infrastructures have such such operations centers) is a unique organizational formation that has evolved in ways to manage systemwide reliability under the pressures of real time. Balances between centralized and decentralized decisonmaking and between error tolerance and error intolerance have to be struck in the form of scenario-based decisions, often just-in-time or just-for now. Otherwise, the lights don’t go on, the water come out of the tap, the 911 call doesn’t connect, and people die.

In narrative analytical terms, the control room as a unique organizational formation for having to take decisions is a powerful engine for reliability professionals producing real-time metanarratives that seek to reconcile, accommodate or otherwise balance all manner of conflicting scenarios so as to underwrite and stabilize taking a decision nevertheless and right now.

REFERENCES [complete from the original publication]

Arrow, K., Bolin, B., Costanza, R., Dasgupta, P., Folke, C., Holling, C. S., Jansson, B. O., Levin, S., Maler, K. G., Perrings, C., & Pimentel, D. (1995). Economic growth, carrying capacity, and the environment. Ecological Economics, 15 (2), 91–95.

Ball, J. (2003, December 10). If an oak eats CO2 in a forest, who gets emission credits? Wall Street Journal, A1, A12.

Barker, D., & Mander, J. (1999). Invisible government–the World Trade Organization: Global government for the new millennium? Primer prepared for the International Forum on Globalization, San Francisco.

Bedsworth L.W., Lowenthal, M. D., & Kastenberg, W. E. (2004). Uncertainty and regulation: The rhetoric of risk in the California low-level radioactive waste debate. Science, Technology & Human Values, 29(3), 406-427.

Belovsky, G. E., Botkin, D.B., Crowl, T.A., Cummins, K.W., Franklin, J.F., Hunter Jr., M.L, Joern, A., Lindenmayer, D.B., MacMahon, J.A., Margules, C.R. & Scott, J.M. (2004). Ten suggestions to strengthen the science of ecology. BioScience, 54, 345-351.

Bogdanor, V. (2003, December 13/December 14). Instant history. Financial Times, W6.

Brown, K. (2002). Water scarcity: Forecasting the future with spotty data. Science, 297, 926-927.

Chambers, R. (1974). Managing rural development: Ideas and experience from East Africa. Uppsala, Sweden: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies Publications.

Chambers, R. (1988). Managing canal irrigation: Practical analysis from South Asia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Chang, K. (2002, September 26). Panel says Bell Labs scientist faked discoveries in physics. New York Times, A1, A20.

Chang, K. (2004, June 15). Researcher loses Ph.D. over discredited papers. New York Times, D2.

Clark, J. A. & May, R. M. 2002. Taxonomic bias in conservation research. Science, 297, 191-192.

Cooper, R. N. & Layard, R. 2002. Introduction. In Cooper, R.N. and R. Layard (Eds.), What the future holds: Insights from social science. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, pp. 1-15.

Crane, N. (2004, February 27). Serious mappers. TLS, 9.

Crossette, B. (2002, August 20). Experts scaling back their estimates of world population growth. New York Times, Retrieved September 29, 2005, from http://www.nytimes.com.

Daugherty, C., & Allendorf, F. (2002). The numbers that really matter. Conservation Biology 16(2), 283-284.

Dugan, I.J. & Berman, D.K. (2004, May 6). Familiar villain emerges in a dark documentary film. Wall Street Journal, B1-B2.

Duvick, D. N. 1999. How much caution in the fields? Science, 286, 418–419.

Scientific fraud: Outside the Bell curve. (2002, September 28). Economist, 73-74.

Ehrlich, P. (2003, January 20). Front-line science does not stand still. Letter to the editor, Financial Times, Retrieved January 20, 2003, from http://www.ft.com.

Feldbaum, C. (2002). Some history should be repeated. Policy Forum. Science, 295, 975.

Flyvbjerg, B., Bruzelius, N., & Rothengatter, W. (2003). Megaprojects and risk: An anatomy of ambition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Global warming—How will It end? [an advertisement] (1999, December 13). New York Times. A16.

Haber, S., North, D.C., & Weingast, B. R. (2003, July 30). If economists are so smart, why is Africa so poor? Wall Street Journal, Retrieved September 29, 2005, from http://www.wsj.com.

Hirschman, A. O. 1967. Development projects observed. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Johnson, K. (2004, June 27). Debate swirls around the status of a protected mouse. New York Times, 14.

Kaiser, J. (2002. August 9). Satellites spy more forest than expected. Science, 297, 919

Kolata, G. (2002, August 29). Beast cancer on Long Island: No epidemic despite the clamor for action. New York Times, A23.

La Porte, T.R. (Ed.). (1975). Organized social complexity: Challenge to Politics and Policy. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Le Blanc, C. (1985). Huan-Nan Tzu: Philosophical synthesis in early Han thought: The idea of resonance (Kan-Ying) with a translation and analysis of chapter six. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Loewe, M. (2003, June 27). Nothing positive. TLS, 28.

Lomborg, B. (2001). The skeptical environmentalist. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lutz, W., O’Neill, B. C., & Scherbov, S. (2003). Europe’s population at a turning point. Policy Forum. Science, 299, 1991-1992.

Mann, C., & Plummer, M. 2002. Forest biotech edges out of the lab. Science, 295, 1626-1629.

March, J. G., Sproul, L. S., & Tamuz,M. (1991). Learning from samples of one or fewer. Organization Science, 2(1), 1–13.

Moris, J. R. (1981). Managing induced rural development. Bloomington, Ind.: International Development Institute, Indiana University.

Myers, N. & Pimm. S. (2003). The last extinction? Foreign Policy, 135, 28-29.

Pikitch, E.K., Santora, C., Babcock, E.A., Bakun, A., Bonfil, R., Conover, D.O., Dayton, P., Doukakis, P., Fluharty, D., Heneman, B., Houde, E.D., Link, J., Livingston, P.A., Mangel, M., McAllister, M.K., Pope, J. & Sainsbury, K.J. (2004). Ecosystem-based fishery management. Policy Forum Science, 305, 346-347

Pimm, S. (2003, January 20). Lomborg overlooked compelling information that did not fit thesis. Letter to the editor, Financial Times, Last accessed September 29, 2005 from http://www.ft.com.

Ramanathan, V., & Barnett, T. P. (2003). Experimenting with Earth. Wilson Quarterly, 27(2), 78-84.

Random samples (2003). Statement by Mark Holland. Science, 300, 247.

Revkin, A. C. (2002, August 20). Forget nature. Even Eden is engineered. New York Times, D1-D5..

Rignot, E., Rivera, A., & Casassa, G. (2003). Contribution of the Patagonia Icefields of South America to sea level rise. Science, 302, 434-437.

Ringen, S. (2003, February 28). Fewer people: A stark European future. TLS, 9-11.

Rochlin, G. I. (1993). Defining “high reliability” organizations in practice: A taxonomic prologue. In Roberts, K.H. (Ed.), New challenges to Understanding Organizations (pp. 11-32). New York: Maxwell Macmillan International.

Roe, E. (1991). Development narratives, or making the best of blueprint development. World Development, 19(4), 287-300.

Roe, E. (1994). Narrative policy analysis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Roe, E. (1995). Except-Africa, postscript to a special section around the 1991″Development Narratives” article. World Development, 23(6), 1065-1069.

Roe, E. (1998). Taking complexity seriously: Policy analysis, triangulation, and sustainable development. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Roe, E. (1999). Except-Africa. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Roe, E. (2004). Real-time ecology. Letter to the editor and interchange. BioScience, 54(8), 716.

Roe, E., & Schulman, P.R. (2008). High Reliability Management. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Roe, E., & Schulman, P.R. (2016). Reliability and Risk. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Roe, E., & Schulman, P.R. (2018). A reliability & risk framework for the assessment and management of system risks in critical infrastructures with central control rooms. Safety Science, 110, 80-88.

Roe, E., & Schulman, P.R. (2023). An interconnectivity framework for analyzing and demarcating real-time operations across critical infrastructures and over time. Safety Science, 168, 106308.

Roe, E., & van Eeten, M. J. G. (2001a). Threshold-based resource management: A framework for comprehensive ecosystem management. Environmental Management, 27 (2), 195-214.

Roe, E., & van Eeten, M. J. G. (2001b). The heart of the matter: A radical proposal. Journal of the American Planning Association, 67(1), 92-98.

Roe, E., & van Eeten, M. J. G. (2002). Reconciling ecosystem rehabilitation and service reliability mandates in large technical systems: Findings and implications of three major US ecosystem management initiatives for managing human-dominated aquatic-terrestrial ecosystems. Ecosystems, 5(6), 509-528.

Roe, E., & van Eeten, M. J. G. (2004). Three—not two—major environmental counternarratives to globalization. Global Environmental Politics, 4(4), 36-53.

Roe, E., van Eeten, M.J.G., Schulman, P.R., & de Bruijne, M. (2002). California’s electricity restructuring: The challenge to providing service and grid reliability. Report prepared for the California Energy Commission, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and the Electrical Power Research Institute. Palo Alto, CA: EPRI (Electric Power Research Institute).

Roe, E., van Eeten, M.J.G., Schulman, P.R., & de Bruijne, M. (2005). High reliability bandwidth management in large technical systems: Findings and implications of two case studies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15, 263-280.

Salim, E. (2004, June 17). The World Bank must reform on extractive industries. Financial Times, 15.

Sayer, J.A., & Campbell, B.M. (2004). The science of sustainable development: Local livelihoods and the global environment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schulman, P.R., Roe, E, van Eeten, M.J.G., & de Bruijne, M. (2004). High reliability and the management of critical infrastructures. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 12(1), 14-28.

Scoones, I. (Ed.). (1996). Living with uncertainty: New directions in pastoral development in Africa. Exeter, Great Britain: Intermediate Technologies Publications.

Service, R. (2002). Bell Labs fires start physicist found guilty of forging data. Science, 298, 30-31.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2003). World Population in 2300: Highlights. New York: United Nations.

van den Bergh, C. J. M. M., & Rietveld, P. (2004). Reconsidering the limits to world population: Meta-analysis and meta-prediction. Biosciences, 54(3), 195-204.

van Eeten, M., & Roe, E. (2002). Ecology, engineering and management: Reconciling ecosystem rehabilitation and service reliability. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vestergaard, F. (2004, February 20). Letter to the editor: Pictures showing retreat of South American glacier cannot be accepted as evidence of global warming. Financial Times, Retrieved, September 29, 2005, from http://www.ft.com.

Walker, B. (1995). National, regional and local scale priorities in the economic growth versus environment trade-off. Ecological Economics, 15 (2), 145–147.

Weisbord, M., & Janoff, S. (1995). Future search. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Welland, M. (2003, April 30). Don’t be afraid of the grey goo. Financial Times, Retrieved September 29, 2005, from http://www.ft.com.

Wolf, M. (2003a, February 26). People, plagues and prosperity. Financial Times, Retrieved September 29, 2005, from http://www.ft.com

Wolf, M.. (2003b, January 14). A fanatical environment in which dissent is forbidden. Financial Times, Retrieved September 29, 2005, from http://www.ft.com

Wright, B. A., & Okey, T.A. (2004). Creating a sustainable future? Letter to the editor, Science, 304, 1903.

Zeng, N. (2003). Drought in the Sahel. Science, 303, 999-1000.

[1] I thank Paul Schulman for the original framework, though he bears no responsibility for my adaptation and application.

2 thoughts on “The problem for Narrative Policy Analysis is not one of operationalizing policy narratives but rather of evaluating them regardless”