1. Climate emergency parsed through a poem by Jorie Graham

–I liken one of our complexity challenges to that of reading Hardy’s “Convergence of the Twain” as if it were still part of the news (it had been written less than two weeks after the sinking of the Titanic).

So too the challenge of reading the first sequence of poems in Jorie Graham’s Fast (2017, Ecco HarperCollinsPublishers). The 17 pages are extraordinary, not just because of pulse driving her lines, but also for what she evokes. In her unfamiliar words, “we are in systemcide”.

–To read the sequence—“Ashes,” “Honeycomb,” “Deep Water Trawling,” and five others—is to experience all manner of starts—“I spent a lifetime entering”—and conjoined ends (“I say too early too late”) with nary a middle in between (“Quick. You must make up your/answer as you made up your//question.”)

Because hers is no single story, she sees no need to explain or explicate. By not narrativizing the systemcide into the architecture of beginning, middle and end, she prefers, I think, evoking the experience of now-time as end-time:

action unfolded in no temporality--->anticipation floods us but we/never were able--->not for one instant--->to inhabit time…

She achieves the elision with long dashes or —>; also series of nouns without commas between; and questions-as-assertions no longer needing question marks (“I know you can/see the purchases, but who is it is purchasing me—>can you please track that…”). Enjambment and lines sliced off by wide spaces also remind us things are not running.

–Her lines push and pull across the small bridges of those dashes and arrows. To read this way is to feel, for me, what French poet and essayist, Paul Valery, described in a 1939 lecture:

Each word, each one of the words that allow us to cross the space of a thought so quickly, and follow the impetus of an idea which rates its own expression, seems like one of those light boards thrown across a ditch or over a mountain crevasse to support the passage of a man in quick motion. But may he pass lightly, without stopping—and especially may he not loiter to dance on the thin board to try its resistance! The frail bridge at once breaks or falls, and all goes down into the depths.

The swiftness with which I cross her bridges is my experience of the rush of crisis. I even feel pulled forward to phrases and lines that I haven’t read yet. Since this is my experience of systems going wrong, it doesn’t matter to me whether Graham is a catastrophizer or not. She takes the certainties and makes something still new.

–I disagree about the crisis—for me, it has middles with more the mess of contingencies and aftermath than beginnings and ends—but that in no way diminishes or circumscribes my sense she’s right when it comes to systemcide: “You have to make it not become/waiting…”

2. Global Climate Sprawl

You get them wrong before you meet them, while you’re anticipating meeting them; you get them wrong while you’re with them; and then you go home to tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again. Since the same generally goes for them with you, the whole thing is really a dazzling illusion empty of all perception, an astonishing farce of misperception. And yet. . .It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.

I suggest that Global Climate Change isn’t just a bad mess; it’s a spectacularly, can’t-keep-our-eyes-off-it, awful mess of getting it wrong, again and again. To my mind, GCC is a hot mess–both senses of the term–now sprawled all over place and time. It is inextricably, remorselessly part and parcel of “living way too expansively, generously.”

GCC’s the demonstration of a stunningly profligate human nature. You see the sheer sprawl of it all in the epigraph, Philip Roth’s rant from American Pastoral. So too the elder statesman in T.S. Eliot’s eponymous play admits,

The many many mistakes I have made My whole life through, mistake upon mistake, The mistaken attempts to correct mistakes By methods which proved to be equally mistaken.

That missing comma between “many many” demonstrates the excess: After a point, we no longer can pause, with words and thoughts rushing ahead. (That the wildly different Philip Roth and T.S. Eliot are together on this point indicates the very real mess it is.)

That earlier word, sprawl, takes us to a more magnanimous view of what is going on, as in Les Murray’s “The Quality of Sprawl”:

Sprawl is the quality of the man who cut down his Rolls-Royce into a farm utility truck, and sprawl is what the company lacked when it made repeated efforts to buy the vehicle back and repair its image. Sprawl is doing your farming by aeroplane, roughly, or driving a hitchhiker that extra hundred miles home…

This extravagance and profligacy–the waste–are not ornery contrarianism. For poet, Robert Frost, “waste is another name for generosity of not always being intent on our own advantage”. If I had my druthers, rename it, “GCS:” Global Climate Sprawl.

3. Power is where it belongs in opera

The last link below is to a very accomplished production of the opera, Il Giustino, by Antonio Vivaldi. There’s lots of stuff about this power of this opera, e.g. from online sources:

Il Giustino relates the appearance of the goddess Fortune to the peasant Giustino, his rise to leadership of the Byzantine army and the defeat of a Scythian army under Vitaliano, and the jealousy of the emperor Anastasio, who suspects Giustino of having designs on his wife Arianna and on the throne itself. misunderstandings straightened out for a peasant to be proclaimed emperor? https://operavision.eu/performance/il-giustino

Love, eroticism, jealousy and intrigue, war and violence, lust for power, tests of courage and great visions: Antonio Vivaldi’s »Il Giustino« offers an action-packed and emotionally charged stage spectacle about the young farmer Giustino’s rise to the apex of Roman politics. https://www.staatsoper-berlin.de/en/veranstaltungen/il-giustino.11043/

As the opera is long, those who can afford 20 minutes to get a sense of what’s on store try from 1:08.20 minutes – 1:28.16 minutes at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cur90vb_5ko&list=RDcur90vb_5ko&start_radio=1 (for those who seek serviceable English subtitles, go to Settings, then Auto-Generate, and click on “English”)

4. War

–I finish reading the Collected Critical Writings of Geoffrey Hill, which discussed a poet I don’t remember reading before, Ivor Gurney. Which in turn sends me to his poems, which leads me to his “War Books” from World War I and the following lines:

What did they expect of our toil and extreme

Hunger - the perfect drawing of a heart's dream?

Did they look for a book of wrought art's perfection,

Who promised no reading, nor praise, nor publication?

Out of the heart's sickness the spirit wrote

For delight, or to escape hunger, or of war's worst anger,

When the guns died to silence and men would gather sense

Somehow together, and find this was life indeed….

The lines, “What did they expect of our toil and extreme/Hunger—the perfect drawing of a heart’s dream?”, reminded me of an anecdote from John Ashbery, the poet, in an essay of his:

Among Chuang-tzu’s many skills, he was an expert draftsman. The king asked him to draw a crab. Chuang-tzu replied that he needed five years, a country house, and twelve servants. Five years later the drawing was still not begun. ‘I need another five years,’ said Chuang-tzu. The king granted them. At the end of these ten years, Chuang-tzu took up his brush and, in an instant, with a single stroke, he drew a crab, the most perfect crab ever seen.

It’s as if Chuang-tzu’s decade—his form of hunger—did indeed produce the perfect drawing. Gurney’s next two lines, “Did they look for a book of wrought art’s perfection,/Who promised no reading, no praise, nor publication?” reminds me, however, of very different story, seemingly making the opposite point (I quote from Peter Jones’ Reading Virgil: Aeneid I and II):

Cicero said that, if anyone asked him what god is or what he is like, he would take the Greek poet Simonides as his authority. Simonides was asked by Hiero, tyrant of Syracuse, the same question, and requested a day to think about it. Next day Hiero demanded the answer, and Simonides begged two more days. Still no answer. Continuing to double up the days, Simonides was eventually asked by Hiero what the matter was. He replied, ‘The longer I think about the question, the more obscure than answer seems to be.’

I think Hiero’s question was perfect in its own right by virtue of being unquestionably unanswerable. In the case of Chuang-tzu, what can be more perfect than the image that emerges, infallibly and unstoppably, from a single stroke? In the case of Simonides, what can be more insurmountable than the perfect question without answer?

–Yet here is Gurney providing the same answer to each question. War ensures the unstoppable and insurmountable are never perfect opposites—war, rather, patches them together as living: Somehow together, and find this too was life.

Ashbery records poet, David Schubert, saying of the great Robert Frost: “Frost once said to me that – a poet – his arms can go out – like this – or in to himself; in either case he will cover a good deal of the world.”

5. An intertextual long run

I’m first asking you to look and listen to one of my favorites, a short video clip of Anna Caterina Antonacci and Andreas Scholl singing the duet, “I embrace you,” from a Handel opera (the English translation can be found at the end of the clip’s Comments):

Antonacci’s performance will resonate for some with the final scene in Sunset Boulevard, where Gloria Swanson, as the actress Norma Desmond, walks down the staircase toward the camera. But intertextuality–that two-way semi-permeability between genres–is also at work. Antonacci brings the opera diva into Swanson’s actress as much as the reverse, and to hell with anachronism and over-the-top.

–Let’s now bring semi-permeable intertextuality closer to public policy and management. Zakia Salime (2022) provides a rich case study of refusal and resistance by Moroccan villagers to nearby silver mining–in her case, parsed through the lens of what she calls a counter-archive:

My purpose is to show how this embodied refusal. . .was productive of a lived counter-archive that documented, recorded and narrated the story of silver mining through the lens of lived experience. . . .Oral poetry (timnadin), short films, petitions, letters and photographs of detainees disrupted the official story of mining ‘as development’ in state officials’ accounts, with a collection of rebellious activities that exposed the devastation of chemical waste, the diversion of underground water, and the resulting dry collective landholdings. Audio-visual material and documents are still available on the movement’s Moroccan Facebook page, on YouTube and circulating on social media platforms. The [village] water protectors performed refusal and produced it as a living record that assembled bodies, poetic testimonials, objects and documents

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/dech.12726

What, though, when the status quo is itself a counter-archive? Think of all the negative tweets, billions and billions and billions of them. Think of all negative comments on politics, dollars and jerks in the Wall Street Journal or Washington Post. That is, think of these status quo repositories as a counter-archive of “status-quo critique and dissent.”

–So what? Consider now the status quo as archives and counter-archives across multiple media that can be thought of as semi-permeable and in two-way traffic over time and space.

This raises an interesting possibility: a new kind of long-run that is temporally long because it is presently intertextual, indefinitely forwards and back and across different genres. As in: “the varieties of revolution do not know the secrets of the futures, but proceed as the varieties of capitalism do, exploiting every opening that presents itself”–to paraphrase political philosopher, Georges Sorel–who, importantly for the point here, could not know all secrets of the past either.

6. Quoting our way to answering, “What happens next?”

I

What to do when there isn’t even a homeopathic whiff of “next steps ahead” in the policy-relevant document you are reading? Yes, it’s a radical critique that tells truth to power, yes it is a manifesto for change now; yes, it’s certain, straightforward and unwavering.

But, like all policy narratives with beginnings, middles and ends, the big question remains: What happens next? Without provisional answers, endings are always immanent. “The thing is that you can always go on, even when you have the most terrific ending,” in the words of Nobel poet, Joseph Brodsky.

What to do? One answer is in Lucretius:

quin etiam refert nostris versibus ipsis

cum quibus et quali sint ordine quaeque locata;

. . .verum positura discrepitant res.

(Indeed in my own verses it is a matter of some moment what is placed next to what, and in what order;…truly the place in which each will be positioned determines the meaning.)

Lucretius, De Rerum Natura

That is, an answer to “What happens next?” is to juxtapose disparate quotes in order to extend the endings we have. This is a high-stakes wager that answers to “What happens next?” are alternative versions of what I would have thought instead. An example is found in II that follows.

II

"Who we are is what we can't be talked out of" Adam Phillips

Large proportions of the Chinese collection are perhaps copies in the eyes of those collectors and dealers, who believe that authentic African art has become largely extinct due to diminishing numbers of active traditional carvers and ritual practices. However, the ideological structure and colonial history of authenticity loses its effects and meanings in China, where anything produced and brought back from Africa is deemed to be “authentically African” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13696815.2021.1925089

But when. . .researching shanzhai art made in Dafen village, located in Shenzhen, Southern China, and home to hundreds of painter-workers who make reproductions in every thinkable style and period, I was struck by the diversity of the artworks and their makers. The cheerfulness with which artworks were altered was liberating, for example, the ‘real’ van Gogh was considered too gloomy by customers, so the painters made a brighter version (see Image 1).

In another instance, I witnessed the face of Mona Lisa being replaced by one’s daughter to make it fit the household. When I brought an artwork home, the gallery called me later to ask if it matched my interior. Otherwise, I could change it. Such practices do turn conventional notions about art topsy-turvy. And shanzhai does not only concern art, it extends to phones, houses, cities, etc. As Lena Scheen (2019: 216) observes,

‘What makes shanzhai truly “unique” is precisely that it is not unique; that it refuses to pretend its uniqueness, its authenticity, its newness. A shanzhai resists the newness dogma dominating Euro-American cultures. Instead, it screams in our faces: “yes, I’m a copy, but I’m better and I’m proud of it”.’ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13675494251371663

So what?

Any realistic attempt of ecological restoration with cloned bucardo [the Pyrenees ibex] would have to rely on hybridisation with other subspecies at some point; the genetic material from one individual could not be used to recreate a population on its own. Juan hypothesised: “we would have had to try to cross-breed in captivity, but you never know what could be possible, with new tools like CRISPR developing… and those [genome editing] technologies that come in the future, well, we don’t know, but maybe we could introduce some genetic diversity. This highlights a fundamental flaw in cloning as a means of preserving ‘pure’ bucardo—not only are ‘bucardo’ clones born with the mitochondrial DNA of domestic goats, but the hypothetical clone would also be subjected to further hybridisation. This begs the question, could such an animal ever be considered an authentic bucardo?” https://rgs-ibg.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/tran.12478

7. Colonial violence, domestic violence: an example of how genre, juxtaposition and intertext matter.

1. “The Canto of the Colonial Soldier” (sung in English with French subtitles). From the opera, Shell Shock, by Nicholas Lens (libretto by Nick Cave) from 3.25 minutes to 10.00 minutes in the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F3bGhqROG8E&list=RDF3bGhqROG8E&start_radio=1

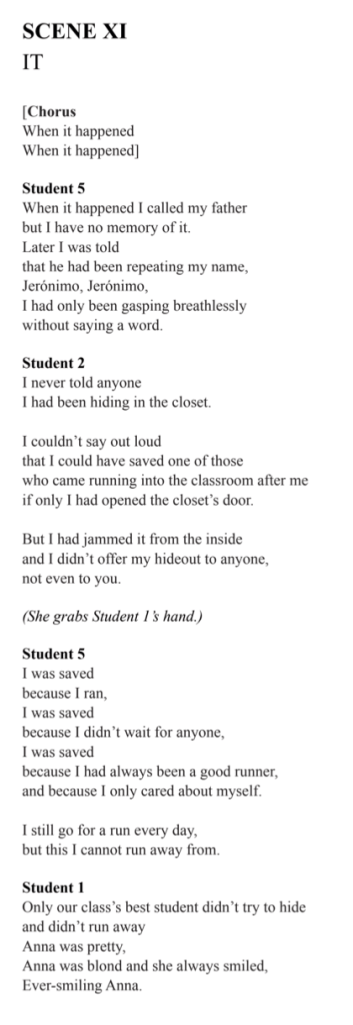

2. “IT” (Scene XI) from the opera, Innocence, by Kaija Saariaho (multilingual libretto by Aleksi Barrière of the original Finnish libretto by Sofi Oksanen) from 44.25 minutes to 49.33 minutes in the following link.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZz2bxnAQfs&lc=Ugzut1S6c6UsP2ED_vx4AaABAg

This particular scene is about a mass school killing, sung by the students and in different languages. You will want to read the English translation before watching the clip.

Saariaho stipulates that the Shooter should not appear on stage at any time, while the Colonial Soldier is the first shooter to be heard in Lens’s work.

English translation of Scene XI, “IT” (from https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/58414/Innocence–Kaija-Saariaho/; sorry for the clumsy cut and paste below)

2 thoughts on “The policy relevance of poetry and opera for climate, war, the long run, violence, power and more”