I

It’s a truism that narratives dominate public policy and management. No more so than in the promise of there being beginnings, middles and ends to this other in medias res realism of complex, uncertain, interrupted and conflicted.

But narrative structures have far more widespread impacts than those associated with conventional beginning/middle/end storylines. There’s always been, by way of example, argument by adjective and adverb. The story goes that Georges Simenon, having finished the typescript of one more novel, would call his children into the room and wave it before them, asking: “What am I doing, little ones?,” to which they would respond, ‘You’re getting rid of the adjectives, papa.” Oh, were that true for the policy advocates writing today!

There is also changing the argument (and its realism) by changing the genre. More formally, consider the importance of differences in narrative structure between a policy brief and a policy report. It’s not just that a policy brief is shorter than the report upon which it is based. Things are left out in the former for reasons other than its shorter length.

A policy brief and a policy report are different genres, like a novel and a play. Their respective styles, voice, conventions, audiences, and even what they take to be details (formally, their granularities) differ substantively.

This means that what’s narrated in one but not repeated in another have implications for policy and management. Indeed, that a brief and a report have been written for different audiences, fulfilling different requirements and expectations, would be a banal observation, where it not for this: While any two genres differ, what each genre takes as “the specifics”–to repeat, the respective granularities–are nevertheless both relevant for real-world policy and management activities.

II

So what?

More generally, in order to say something new about a difficult policy issue or see it afresh, change the genre within which you think and write about it. The academic article, a short blog, the format of a play, an “I-believe” manifesto and not just those memos and briefs–all and more have their own conventions. To take a major “intractable” policy issue you’ve read about in one medium and then focus the dense dark beam of altogether unfamiliar conventions over it, is to see what is left to glimmer there by way of ambiguities.

I now want to delve into how other differences in genre matter for specific policy and management. I’m particularly interested in how different genres pose specifics that are, more obviously than not, actionable with respect to policy and management.

I turn now to sixteen examples of what I mean and their “So what?” implications.

1. “‘It will be unimaginably catastrophic” as a genre limitation of the interview format

2. The genre of wicked policy problems

3. Catastrophized cascades

4. The genre of policy palimpsest

5. Policy as memoir, memoir as policy

6. Journalism, academic articles and my profession, policy analysis

7. The formulaic radicalism of academic articles in search of policy relevance

8. An infinite regress for the purposes of “So what?” explains nothing

9. How being right is a matter of genre

10. The journal article as manifesto: a Horn of Africa example

11. The petition as a major but under-recognized policy genre

12. Surprising genre in policy analysis

13. Mixing Donald Rumsfeld and Christopher Bollas: complicating typologies (newly added)

14. Rescuing the case study (newly added)

15. Mestizaje, Or: ChatGPTs (newly added)

16. Colonial violence & domestic terror: another example of how genre renders center-stage (newly added)

—-

1. “It will be unimaginably catastrophic” as a genre limitation of the interview format

I

Our interviewees have been insistent: A magnitude 9.0 Cascadia earthquake will be unimaginably catastrophic. The unfolding would be unprecedented in the Pacific Northwest as nothing like it had occurred there before. True, magnitude 9.0 earthquakes have happened elsewhere. But there was no closure rule for thinking about how this earthquake would unfold in Oregon and Washington State, given their specific interconnected infrastructures and populations.

Fair enough, but not enough.

So many interviewees made this observation, you’d have to conclude the earthquake is predictably unimaginable to them. The M9 earthquake isn’t totally incomprehensible, like unknown-unknowns. Rather it is a known unknown, something along the lines of that mega-asteroid hit or a modern-day Carrington event.

II

I however think something else is also going on in these interviewee comments. It has to do with the interview as its own genre.

American author, Joyce Carol Oates, recently summed up its limitations to one of her interviewers:

David, there are some questions that arise when one is being interviewed that would never otherwise have arisen. . .I focus so much on my work; then, when I’m asked to make some abstract comment, I kind of reach for a clue from the interviewer. I don’t want to suggest that there’s anything artificial about it, but I don’t know what I’m supposed to say, in a way, because I wouldn’t otherwise be saying it. . .Much of what I’m doing is, I’m backed into a corner and the way out is desperation. . .I don’t think about these things unless somebody asks me. . .There is an element of being put on the spot. . .It is actually quite a fascinating genre. It’s very American: “The interview.”

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/07/16/magazine/joyce-carol-oates-interview.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare&utm_source=Sailthru&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Lit%20Hub%20Daily:%20July%2019%2C%202023&utm_term=lithub_master_list

Elsewhere Oates adds about interviewees left “trying to think of reasonably plausible replies that are not untrue.” I suspect such remarks are familiar to many who have interviewed and been interviewed.

III

I believe our interviewee statements to the effect that “The M9 earthquake will be unimaginably catastrophic” also reflect the interview genre within which this observation was and is made. The interviewees felt put on the spot while answering about other important work matters. They wanted to be just as plausible as in their earlier knowledgeable answers. That is, “unimaginably catastrophic” is not untrue, while however without having to specify how true. Such is the statement’s recourse to argument by adverb.

So what?

“Anyway, this is not to say that there was anything wrong about my statement to you,” adds Oates. “It’s that there’s almost nothing I can say that isn’t simply an expression of a person trying desperately to say something”—this, here, being something about a catastrophe “desperately very” indeed.

—-

2. The genre of wicked policy problems

Recast wicked (that is, intractable) problems of policy and management as part of a longstanding genre in literature, which enables very different statements and competing positions to be held without them being inconsistent at the same time. Literary and cultural critic, Michael McKeon, helps us to do so:

Genre provides a conceptual framework for the mediation (if not the “solution”) of intractable problems, a method for rendering such problems intelligible. The ideological status of genre, like that of all conceptual categories, lies in its explanatory and problem-“solving” capacities.

In McKeon’s formal terms, “the genre of the novel is a technique to engage epistemological and socio-ethical problems simultaneously, but with no particular commitment than that.”

Intractability appeared not only as the novel’s subject matter but also by virtue of the conventions for how these matters to be raised. The content is not only about the intractable, but also its governing context is as historically tangled and conventionalized as that of the English novel.

So what?

I am not saying wicked problems are fictitious (even so, there is the well-known truth in fiction). Rather, I am arguing that pinning wicked problems exclusively to their content (e.g., wicked problems are defined by the lack of agreed-upon rules to solve them) misses the fact that the analytic category of wicked problems as such is highly rule-bound (i.e.., by the historical conventions to articulate and discuss such matters, in this case through novelistic means).

How so? Return to the scholarly attempt to differentiate “wicked” and “tame” problems into more nuanced categories. Doing so is akin to disaggregating the English novel into romance, historical, gothic and other types. But such a differentiation need not problematize the genre’s conventions. In fact, the governing conventions may become more complex for distinguishing the more complex content, thus reinforcing the genre as a bottled intractability.

If wicked problems are to be better addressed, altogether different conventions and rules—what Wittgenstein called “language games”—will have to be found under which to recast these. . . . well, whatever they are to be called they wouldn’t be termed “intractable, full stop,” would they? Declaring something a wicked problem creates The Ultimate One-Sided Problem—it’s, well, intractable—for humans who are everything but one-sided.

—-

3. Catastrophized cascades

The upshot of what follows: Infrastructure cascades and the genre of catastrophizing about large system failure have a great deal in common and this has major implications for policy and management.

I

An infrastructure cascade happens when the failure of one part of the critical infrastructure triggers failure in its other parts as well as in other infrastructures connected with it. The fast propagation of failure can and has led to multiple systems failing over quickly, where “a small mistake can lead to a big failure.” The causal pathways in the chain reaction of interconnected failure are often difficult to identify or monitor, let alone analyze, during the cascade and even afterwards.

For its part, catastrophizing in the sense of “imagining the worst outcome of even the most ordinary event” seems to overlap with this notion of cascade. Here though the imagining in catastrophizing might be written off as exaggerated, worse irrational—the event in question is, well, not as bad as imagined—while infrastructure cascades are real, not imagined.

II

We may want, however, to rethink any weak overlap when it comes to infrastructure cascades and catastrophizing failure across interconnected infrastructures. Consider the insights of Gerard Passannante, Catastrophizing: Materialism and the Making of Disaster (2019, The University of Chicago Press).

In analyzing cases of catastrophizing (in Leonardo’s Notebooks, an early work of Kant and Shakespeare’s King Lear, among others), Passannante avoids labeling such thinking as irrational and favors a more nuanced understanding. He identifies from his material four inter-related features to the catastrophizing.

First (no order of priority is implied), catastrophizing probes and reasons from the sensible to the insensible, the perceptible to the imperceptible, the witnessed to the unwitnessed, and the visible to invisible. In this fashion, the probing and reasoning involve ways of seeing and feeling as well.

Second and third, when catastrophizing, an abrupt, precipitous shift or collapse in scale occurs (small scale suddenly shifts to large scale), while there is a distinct temporal elision or compression of the catastrophe’s beginning and end (as if there were no middle duration to the catastrophe being imagined).

Last, the actual catastrophizing while underway feels to the catastrophizer as if the thinking itself were involuntary and had its own automatic logic or necessity that over-rides—“evacuates” is Passannante’s term—the agency and control of the catastrophizer.

III

In this way, the four features of catastrophizing take us much closer to the notion of infrastructure cascades as currently understood.

In catastrophizing as in cascades, there is both that rapid propagation from small to large and that temporal “failing all of a sudden.” In catastrophizing as in cascades, causal connections—in the sense of identifying events with their beginnings, middles and ends—are next to impossible to parse out, given the rapid, often inexplicable, processes at work.

And yes, of course, cascades are real, while catastrophizing is more speculative; but: The catastrophizing feels very, very real to–and out of the direct control of–the catastrophizer as an agent in his or her own right.

In fact, one of the most famous typologies in organization and technology studies sanctions a theory that catastrophizes infrastructure cascades. The typology’s cell of tight coupling and complex interactivity is a Pandora Box of instantaneous changes, invisible processes, and incomprehensible breakdowns involving time, scale and perspective.

This is not a criticism: It may well be that we cannot avoid catastrophizing, if only because of the empirical evidence that sudden cascades have happened in the past.

IV

So what?

The four features suggest that one way to mitigate any wholesale catastrophizing of infrastructure cascades is to bring back time and scale into the analysis and modeling of infrastructure cascades.

To do so would be to insist that really-existing infrastructure cascades are not presumptively instantaneous or nearly so. It would be to insist that infrastructure cascades are differentiated in terms of time and scale, unless proven otherwise.

Allow me to end with an extended quote from our own research:

One clear objective of recent network of networks modeling has been finding out which nodes and connections, when deleted, bring the network or sets of networks to collapse. Were only one more node to fail, the network would suddenly collapse completely, it is often argued…

But ‘suddenly’ is not all that frequent at the [interconnected infrastructure] level. In fact, not failing suddenly is what we expect to find in managed interconnected systems, in which an infrastructure element can fail without the infrastructure as a whole failing or disrupting the normal operations of other infrastructures depending on that system. Infrastructures instantaneously failing one after another is not what actually happens in many so-called cascades, and we would not expect such near simultaneity from our framework of analysis.

Rapid infrastructure cascades can, of course, happen….Yet individual infrastructures do not generally fail instantaneously (brownouts may precede blackouts, levees may seep long before failing), and the transition from normal operation to failure across systems can also take time. Discrete stages of disruption frequently occur when system performance can still be retrievable before the trajectory of failure becomes inevitable.

E. Roe and P.R. Schulman, Risk and Reliability, 2016, Stanford University Press,

—-

4. The genre of policy palimpsest

I

The notion of “policy palimpsest” arose early on in policy studies, but never gained much traction. Its upshot is that current statements about complex policy issues are the composites of arguments and narratives that have been overwritten across time. Any composite argument rendered off a policy palimpsest reads sensibly—nouns and verbs appear in order and sense-making is achieved—but none of the previous inscriptions or points are pane-clear and whole through the layers, effacements, and erasures. Arguments have been blurred, intertwined and re-assembled for present, at times controverted, purposes.

By way of example, consider what was a longstanding commonplace: “Nazi and communist totalitarianism has come to mean total control of politics, economics, society and citizenry.”

In reality, that statement was full of effacements from having been overwritten again and again through seriatim debates, vide:

“……totalitarianism has come to mean…….total control of politics ,citizenry and economics………”

It’s that accented “total control” that drove the initial selection of the phrases around it. Today, after further blurring, it’s more fashionable to rewrite the composite argument as: “Nazi and communist totalitarianism sought total control of politics, economics, society and citizenry.” The “sought” recognizes that, when it comes these forms of totalitarianism, seeking total control did not always mean total control achieved. “Sought” unaccents “total control.”

II

Fair enough, but note that “sought” itself reflects its own effacements in totalitarianism’s palimpsest, with consequences for how time and space are re-rendered.

Consider two quotes from the many in that policy palimpsest, which are missed when it comes to the use of a reduced-form “sought”:

I always thought there must be some more interesting way of interpreting the Soviet Union than simply reversing the value signs in its propaganda. And the thing that first struck me – that should have struck anybody working in the archives of the Soviet bureaucracy – was that the Soviet leaders didn’t know what was happening half the time, were good at throwing hammers at problems but not at solving them, and spent an enormous amount of time fighting about things that often had little to do with ideology and much to do with institutional interests.

https://www.lrb.co.uk/v32/n23/sheila-fitzpatrick/a-spy-in-the-archives

The camp, then, was always in motion. This was true for people and goods, and also for the spaces they traversed. Because Auschwitz was one big construction site. It never looked the same, from one day to the next, as buildings were demolished, extended and newly built. As late as September 1944, just months before liberation in January 1945, the Camp SS held a grand ceremony to unveil its big new staff hospital. . .

Inadvertently, [construction] also created spaces for prisoner agency. The more civilian contractors worked on site, the more opportunities for barter and bribes. All the clutter and commotion also made it harder to exercise full control, as blocked sightlines opened the way for illicit activities, from rest to escape. . .

Some scholars see camps like Auschwitz as sites of total SS domination. This was certainly what the perpetrators wanted them to be. But their monumental designs often bore little resemblance to built reality. Priorities changed, again and again, and SS planners were thwarted by supply shortages, bad weather and (most critically) by mass deaths among their slave labour force. In the end, grand visions regularly gave way to quick fixes, resulting in what the historian Paul Jaskot, writing about the architecture of the Holocaust, called the “lack of a rationally planned and controlled space”. Clearly, the popular image of Auschwitz as a straight-line, single-track totalitarian machine is inaccurate.

https://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/being-in-auschwitz-nikolaus-wachsmann/

I am not arguing that the quoted reservations are correct or generalizable or fully understandable (the quotes come to us as already overwritten). I am saying that they fit uncomfortably with popular notions “local resistance,” when the latter is about “taking back control”

III

So what?

So what if time and space are in a policy and management world are (re-)rendered sinuous and interstitial, in a word, anfractuous rather than linear like a sentence? It’s a big deal, actually.

It means that no single composite argument can galvanize the entire space-and-time of a palimpsest. It means matters of time and space are always worth another look with each argument we read off of a major policy.

For instance, the preceding entry noted how “catastrophic cascades” are described as having virtually instantaneous transitions from the beginning of a cascade in one infrastructure to its awful conclusion across other infrastructures connected with it. But in the terminology presented here, a catastrophizing cascade isn’t so much a composite argument with a reduced-form middle as it is a highly etiolated palimpsest where infrastructure interactions taking more granular time and space have been blotted out altogether.

—-

5. Policy as memoir, memoir as policy

Some of you may remember when the orbiting twins of “freedom and necessity” shone bright and high in the intellectual firmament. Now it’s capitalism all the way down. And yet the second you differentiate that capitalism you are back to limits and affordances, constraints and enablements–in a phrase back to the varieties of freedom and necessity.

None of this would matter if the macro-doctrinal and personal-experiential were nowhere the same. But the macro-doctrinal and personal-experiential are, I want to argue, conflated and treated as one and the same in at least one major public domain: namely, where stated policies become more and more like memoirs, and where memoirs are cast more as policy statements.

II

Recently, Sallie Tisdale, writer and essayist, makes the point directly:

Today autobiography seems to be a litany of injury, the recounting of loss and harm caused by abuse, racism, abandonment, poverty, violence, rape, and struggle of a thousand kinds. The reasons for such a shift in focus, a shift we see in every layer of our social, cultural, and political landscapes, are beyond my scope. One of the pivotal purposes of memoir is to unveil the shades of meaning that exist in what we believe. This is the problem of memoir; this is the consolation of memoir. Scars are fine; I have written about scars; it is the focus on the unhealed wound that seems new.

https://harpers.org/archive/2023/11/mere-belief/?src=longreads

Memoir in this shift ends up, in Tisdale wonderful term, as a “grand reveal.” Of course, policy and management should be concerned with abuse, racism, abandonment, poverty, violence, rape, and struggle of a thousand kinds. It’s that exclusionary focus on the unhealed wound that is the problem, at least for those who take their scars and wounds also to be affordances and enablements.

To collapse this complexity of memory and experience into “identity” and/or “politics” is to exaggerate one meaning at the expense of the others. To quote Tisdale again: “I used to think that I would be a good eyewitness. Now I no longer trust eyewitnesses at all.”

So what?

To rewrite a once-popular expression, both freedom and necessity are the recognition of how unreliable we are in eye-witnessing what is right in front of us. One thinks of George Orwell’s point: “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.”

—-

6. Journalism, academic articles and my profession, policy analysis

When it comes to the policy relevance of journalism and my profession, policy analysis, it’s been a matter of genre differences for as long as I can remember.

The journalist article starts with the victim, when policy professionals want to know upfront not what’s wrong, but what’s actually working out there by way of strategies to reduce said victimhood. For my part, I want to know right off how people with like problems are jumping a like bar of politics, dollars and jerks better than we are. Something must be working out there; we’re a planet of 8 billion people, after all!

And to be clear about the “So what?“. No need for academic articles to lead with: “We are currently living in an age of multiple closely interconnected and intensifying crises. There is growing awareness that questions of diversity and representation matter in scholarship. Conservation is at a crossroads. Numbers occupy a central place in global governance.”

Rather, tell us upfront something we don’t know and their implications, in order that different types of readers for policy relevance have energy to scan the rest. We’re not asking the authors to simplify. We’re asking them to tell us what they conclude or propose so we, these different readers, can decide whether or not their analysis supports their case. Indeed, tell us upfront because we may find we have something better to recommend—including different media for putting them.

—-

7. The formulaic radicalism of academic articles in search of policy relevance

A third problem is Formulaic radicalism. This is an attempt to project a veneer of political and intellectual dissidence while ultimately relying on highly established tropes which often lead to unsurprising conclusions. Contemporary research is generally formulaic but [critical management studies, CMS] adds the critical flavour. It often does so by giving phenomena – no matter how benign – a negative framing.

Studying ‘resistance’ gives a progressive, even heroic flavour to a topic. One way CMS researchers do formulaic radicalism is by using conventional formats but include some markers of radicalism. The author may seek to express radical and critical ideas while complying with ‘mainstream’ conventions. Such a move can help to indicate that a study is clearly positioned in an academic subfield, guided by an authoritative framework, and informed by a detailed review of the literature.

Next the research outlines a planned design, a careful data management strategy (sometimes using data sorting programs and codification), and a minor section of ‘safe’ reflexivity. The authors summarize findings, outlines how they add to the literature (and sometimes the author-ity [sic]) and offers a brief conclusion (not saying too much outside the chosen and mainly predictable path). The form should matter less than the content, but this highly domesticated form tends to weaken the impact of the substantive content. The norm of presenting a number of abstracted, short interview statements does not always help to reveal any particularly novel insights.

In the text, there are frequent nods to critical aims such as exploring power, supporting emancipation, recognizing resistance, or generating reflexivity. However, the formulaic presentation of findings often undermines this [“So what?”] and leads to modest insights.

André Spicer and Mats Alvesson (2024). “Critical Management Studies: A Critical Review.” Journal of Management Studies (accessed online at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/joms.13047)

—-

8. An infinite regress for the purposes of “So what?” explains nothing

Stop fossil fuels; stop cutting down trees; stop using plastics; stop defense spending; stop being imperialist; stop techno-solutionism; start being small-d democratic and small-p participatory; dismantle capitalism; transform cities; save biodiversity; never forget class, gender, race, inequality, religions, bad faith, identity. . . and. . .

—-

9. How being right is a matter of genre

In public policy, the wish–so often unfilled–is for the right person at the right time in the right job doing the right thing.

In poetry by contrast, we have Louise Glück’s poem, “Crossroads,”

My body, now that we will not be traveling together much longer

I begin to feel a new tenderness toward you, very raw and unfamiliar,

like what I remember of love when I was young—love that was so often foolish in its objectives

but never in its choices, its intensities.

Too much demanded in advance, too much that could not be promised—My soul has been so fearful, so violent:

forgive its brutality.

As though it were that soul, my hand moves over you cautiously,not wishing to give offense

but eager, finally, to achieve expression as substance:it is not the earth I will miss,

it is you I will miss.

Given the poem’s theme, the shortening of lines from three to two is so RIGHT! Here the answer to question, “So what by way of ‘right’?” is the answer, “What else but these last two?”

—-

10. The journal article as manifesto: a Horn of Africa example

To be clear: I agree with the manifesto below. But that agreement is not because it’s published as a formal journal article. Instead, I believe it because, as a manifesto, it demands change now in terms I understand and appreciate historically.

Since my argument depends on the definition of “manifesto” I use, here’s mine:

Always layered and paradoxical, [a manifesto] comes disguised as nakedness, directness, aggression. An artwork aspiring to be a speech act—like a threat, a promise, a joke, a spell, a dare. You can’t help but thrill to language that imagines it can get something done. You also can’t help noticing the similar demands and condemnations that ring out across the decades and the centuries— something will be swept away or conjured into being, and it must happen right this moment. . .This is a form that asks readers to suspend their disbelief, and so like any piece of theater, it trades on its own vulnerability, invites our complicity, as if only the quality of our attention protects it from reality’s brutal puncture. A manifesto is a public declaration of intent, a laying out of the writer’s views (shared, it’s implied, by at least some vanguard “we”) on how things are and how they should be altered. Once the province of institutional authority, decrees from church or state, the manifesto later flowered as a mode of presumption and dissent. You assume the writer stands outside the halls of power (or else, occasionally, chooses to pose and speak from there). Today the US government, for example, does not issue manifestos, lest it sound both hectoring and weak. The manifesto is inherently quixotic—spoiling for a fight it’s unlikely to win, insisting on an outcome it lacks the authority to ensure.

L. Haas (2021). “Manifesto Destiny: Writing that demands change now.” Bookforum accessed online at https://www.bookforum.com/print/2802/writing-that-demands-change-now-2449

In 2023, Mark Duffield and Nicholas Stockton published, “How capitalism is destroying the Horn of Africa: sheep and the crises in Somalia and Sudan,” in the peer-reviewed Review of African Political Economy (https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03056244.2023.2264679). To its credit, the Review publishes “radical analyses of trends, issues and social processes in Africa, adopting a broadly materialist interpretation of change.” And what a breadth of fresh air this article is.

First, its tone is direct, its language unequivocally materialist in the great manner of yesterday, its focus is on the marginalized, and how could we not want change after reading this?

We present in outline an historically and empirically grounded explanation for the post-colonial destruction of the nation states of Somalia and Sudan. This is combined with a forecast that the political de-development of the Horn, and of the Sahel more generally, is spreading south into East and Central Africa as capitalism’s food frontier, in the form of a moving lawless zone of resource extraction. It is destroying livelihoods and exhausting nature. Our starting point is Marx’s argument that the historical growth and the continuing development of capitalism is facilitated through what he called ‘primitive accumulation’. With regard to the current situation in the Horn, there is a sorry historical resonance with the violent proto-capitalist land clearances that took place from the sixteenth century onward in England, Ireland and Scotland and then in North America. While today, as in Darfur, this may be classified as genocide, the principal purpose of land clearances is to convert socially tilled soils and water resources used for autonomous subsistence into pastures for intensive commercial livestock production, which now in Somalia and Sudan amounts to nothing short of ‘ecological strip mining’.

To repeat, how could you (we) not want radical change when reading further:

. . .we argue that the trade is intimately connected with the deepening social, economic and ecological crisis of agro-pastoralism in the region and the way that livestock value is now realised. Underlying the empirical data is the intensification of an environmentally destructive mode of militarised livestock production that, primarily involving sheep, is necessarily expansive, land-hungry, livelihood destroying and population displacing. Sustained by raw violence and strengthened by United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi investment in Red Sea port infrastructure, the Horn and the Gulf are locked into a deadly destruction–consumption embrace.

More, there is a singular cause and it is clear: “This internationally facilitated mode of appropriation, with its associated acts of land clearance, dispossession and displacement, is the root cause of the current crisis.” Nor is there anything really complex about this:

The depth and cruel nature of the changes in Sudan and Somalia’s agro-pastoral economies cannot reasonably be attributed only to environmental change, scarcity-based inter-ethnic conflict, or avaricious generals per se. To lend these arguments weight, some hold that they combine to produce a ‘complex’ emergency. The only complexity, however, is the contortions necessary to fashion a parallel universe that usefully conceals the rapacity of capitalism. Particularly cynical is the claim, for example, that Somalia’s long-history of de-development is the result of climate-change-induced drought. It is no accident that the same international powers and agencies fronting this claim have, for decades, been active players in the Horn’s de-development.

You cannot imagine how much I want to believe these words! And I take that to be a good measure of just how effective a manifesto this manifesto is, at least for someone like myself.

So what? Manifestos are their own public genre, whatever the publication venue. This is not a policy memo whose second sentence after the problem statement is the answer to: What’s to be done and how? But then we would never look to manifestos for the devil in the details, would we?

—

11. The petition as a major but under-recognized policy genre

Furthermore, the petitions held within the NRC [Ghana’s National Reconciliation Commission] archive highlight the agency of Ghanaians within this process. Far from ideas about good governance being enforced on Ghana from abroad through the implementation of a truth commission, the petitions submitted to the NRC demonstrated that many Ghanaians had developed ideas of what constituted a good and bad citizen based on their own lived experiences. The NRC archive represents a vast and rich collection not just of Ghanaian experiences of human rights abuses in the postcolonial era, but of attempts to produce and reproduce a moral economy which counteracted those abuses. These petitions, when viewed as a genre, outlined a consistent and coherent perspective on what good and bad citizens do.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00220094241263787

We forget at our peril that new policy narratives–in this case about citizenship–can be assembled from under-acknowledged policy genres–in this case petitions to truth commissions. So what? Well, for one thing, such a petition becomes a very public practice to decommodify already-commodified consumers and voters.

—

12. Surprising genre in policy analysis

I

Many people would probably think that writing down what they already think is an important part of any policy analysis. It’s a commonplace among many different types of authors, however, that they don’t know what they think until they actually write it down.

“My writings, in prose and verse, may or may not have surprised other people; but I know that they always, on first sight, surprise myself,” writes T.S. Eliot. Chimes in political scientist Aaron Wildavsky, “I do not know what I think until I have tried to write it’. “Writing is thinking; writing is a form of thought,” the journalist William Langewiesche said, adding “It’s difficult for me to believe that real thought is possible without writing.” “You never know what you’re filming until later”, remarks a narrator in Chris Marker’s 1977 film Le Fond de l’Air est Rouge. A well-known curator admits, “But then, often when I sit down to write the catalogue text, I discover that it’s actually about something else”. J.M. Coetzee, Nobel novelist, manages to make all this sound quite known: “Truth is something that comes in the process of writing, or comes from the process of writing”.

So too I argue for policy analysts writing up their analyses. But a caveat is needed: Analyses come via many different genres, and not all are conducive to surprising oneself with respect to what one really thinks given the evidence now in front of them.

II

Such is the point made by contemporary art critic, Sean Tatol, in a recent edited panel exchange: “When I’m writing, I’m in the process of writing down my thoughts either to formulate something that I haven’t thought of before or to come to a conclusion that’s a surprise to me. That sense of development in thought is, I think, to me the most gratifying. But I think in terms of my short-form reviews that happens very seldom.”

Policy analysts as well have their short-form versions. But one cannot generalize here. The email may well be more surprising for analytical purposes than that article. Two policy briefs, one by a policy advocate who already knows the answer before touching fingers to keyboard, and the other by the policy analyst who holds off rewriting until seeing what they’ve first typed, are quite different matters.

So what you ask? The answer returns us to the starting point of this blog entry: The more genres that the policy analyst has access to and is adept in, the more likely that catalyst of analytic surprise is to be found.

—

13. Mixing Donald Rumsfeld and Christopher Bollas: complicating typologies (newly added)

I

Consider the familiar two-by-two typology that produces known knowns, unknown knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns. In this sequence, we may think all the bases are covered. Now throw in an apparently related term, but from a different field entirely, namely: the “unthought known” of Christopher Bollas, a concept as well known in psychoanalysis. Mix two genres–Rumsfeld’s fourfold typology and Bollas’s psychoanalytic insight–and you realize the initial distinctions are more complicated.

Known-unknowns are said to be risks that we are aware of, but we don’t fully understand. For example, we may know that there is always a risk of a new competitor entering the market or political arena, but we don’t know how likely this is or what impact it would have on competition or politics. Unknown-knowns are said to be things you’re not aware of but do understand. For example, you know gender bias, but didn’t know it was actually happening in the competitive process of interest to you.

II

The unthought known, however, is a kind of knowing that you have not thought about. It is unconscious and often associated with trauma, rendering the unthought known, “unconsciously compelling,” as Bollas puts it. For instance, you know you’re (un)safe without even having to think about it.

How so? Return again to competition and the economic literature on all manner of non-conscious herding behavior, bandwagon effects and market contagion under conditions of deep uncertainty and rapid imitation. Here economic meltdowns, burst financial bubbles and scapegoating give birth to new market rules and wraparound structures, safer for some but not for others.

These phenomena may seem like unknown knowns–we know herding behavior when we see it!–but one must wonder if they are understood psychoanalytically or mimetically as described and formulated.

Unthought knowns, I submit, remain highly policy-relevant, even if the concept doesn’t fit squarely in with known knowns, unknown unknowns, known unknowns, and unknown knowns.

—

14. Rescuing the case study (newly added)

Malena López Bremme and Salvador Santino Regilme present a fabulous case study of the Syrian refugee crisis in their “Climate Change, Ecocide, and the Rise of Environmental Refugees: The Case of Syria” (2025, Political Studies, accessed online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00323217251382404?utm_source=researchgate). Starting on article’s page 8, their case study is detailed, wide-ranging and, as far as I can determined, conclusive:

This case study identifies Syria’s prolonged dictatorship as a period characterized by ecological risks and mismanagement, culminating in protracted war and forced displacement. It explores the climate-conflict hypothesis related to environmental migration, interconnected through a complex chain of water scarcity, drought, governmental neglect, agricultural failure, socioeconomic decline, political oppression, rural-urban competition, internal displacement, civil unrest, and the involvement of regional and global actors. (my bold)

where the hypothesis in question was:

Rather than treating environmental stress as a direct trigger of violence, [the article] theorizes vulnerability as co-produced— arising from the interaction of climate-induced degradation, authoritarian governance, institutional neglect, and deep-rooted socioeconomic inequalities. In the Syrian case, prolonged drought was not a singular cause but one element in a relational and contingent configuration of crisis. Syria thus exemplifies how environmental stress becomes politically explosive under specific governance failures and international conditions. (terms highlighted in the article)

Co-produced, relational and contingent indeed make for complex chains of causality. I strongly encourage the reader interested in the topic of climate refugees to read this article, particularly pp. 8 – 16.

What I find more questionable is the chief policy implication drawn, namely: “the necessity for global governance to address the ecological and humanitarian impacts of climate-induced conflicts.”

One can well agree with the authors that the case illustrates what can happen with “sovereign abandonment—a mode of power where state inaction or deliberate neglect leads to death and displacement.”

But, even where true, the chief policy implication isn’t then: global governance is required. Rather, the immediate implication is: Don’t abandon sovereignty elsewhere if only because the Syrian case study establishes a counterfactual demonstrably worse. The necessity of protecting positive forms of national sovereignty–humane, non-ecocidal–is not, I think, what the authors are recommending.

So what? One would be hard-pressed to say that novels–which when they work are their own form of case studies–argue for global governance. Or more positively, perhaps the latter is now the function of science fiction and the increasing calls to incorporate speculative fiction into policy formulation.

—

15. Mestizaje, Or: ChatGPTs (newly added)

I’m reading an article on LatamGPT, the development of a Latin American version of ChatGPT:

When researchers from the LatamGPT project asked ChatGPT for a 500-character description of Latin American culture, the response was polite but revealing: “Latin American culture is a vibrant amalgam of Indigenous roots, African influences, and European heritage. It is characterized by its rich diversity in music, dance, and cuisine, reflected in festivals like Carnival and the Flower Fair.” While the formulation may seem inclusive, what it reveals is a superficial and standardized understanding of a region marked by the imperial overseas conquest and colonization, through which a mestizaje of exceptional density and complexity took place—rarely found elsewhere in the world—whose tensions, memories, and ways of life far exceed any tourist postcard or folkloric representation. In its stylistic correctness, the response betrays the limits of an AI trained from outside the experience it aims to describe.

(https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11569-025-00480-1; internal footnote deleted_

Sounds right, but what does “mestizaje” mean, you and I ask? The article further along produces the synonym, “hybridization”, but nothing formal.

So I google: “mestizaje meaning.” Oops, the first thing that pops up is the AI-generated:

Mestizaje is a term for the mixing of different racial and cultural groups, historically referring to the blending of Spanish and Indigenous peoples in the Americas, but also including the later addition of African, Asian, and other ancestries. Beyond just race, it encompasses the fusion of languages, customs, and religions that occurred during and after Spanish colonization, and the term is still used today to describe mixed-ancestry identities and cultural exchange. It is a complex concept that is sometimes critiqued for oversimplifying identity, but it remains a significant part of many national identities in the Americas.

Well, this covers some of what the article’s authors describe, but then again, there’s that use of the contentious term, race. . .

So I end up searching further down the search results and find:

“Mestizaje,” which is associated with the word “mixed,” can be understood as the product of mixing two distinct cultures—that is, Spanish and Indigenous American. While it is etymologically connected to the French métis (a person of mixed ancestry, similar to mestiza/o in Spanish) and métissage (the cultural process that leads to this) and to the Portuguese mestiço (a person of mixed ancestry), it is an unstable signifier that has different meanings depending on its context. Referring to the biological and cultural mixing of European and Indigenous peoples in the Americas, mestizaje can be understood as the effect caused by the impact of colonization. In North America, the closest approximation to “mestizaje” is the word métis, indicating a person of mixed aboriginal and European ancestry. For example, in western Canada the term is used in reference to people of Caucasian and Native Indian ancestry. However, both métissage and métis are used primarily in Francophone culture and literature. English, on the other hand, has no equivalent for “mestizaje,” although in theory, it has been identified as synonymous with cultural hybridization or hybridity, as both represent the space-in-between (Anzaldúa 1987; Bhabha 1994; García Canclini 1995).

(https://keywords.nyupress.org/latina-latino-studies/essay/mestizaje/)

Kind of Eurocentric, but, hey, it gets us back to “hybridization”, the synonym in the original article. Still, there’s nothing explicit about cuisine (as in the article’s quoted passage), and what about that bit about mestizaje being “an unstable signifier”?

I have no problem with mestizaje being complex, but I wonder what any GPT prompt-and-response can say about the term’s continuing significance as an unstable signifier?

—

16. Colonial violence & domestic terror: another example of how genre renders center-stage (newly added)

–Start with “The Canto of the Colonial Soldier” (sung in English). From the opera, Shell Shock, by Nicholas Lens (libretto by Nick Cave) from 3.25 minutes to 10.00 minutes in the following link:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F3bGhqROG8E&list=RDF3bGhqROG8E&start_radio=1

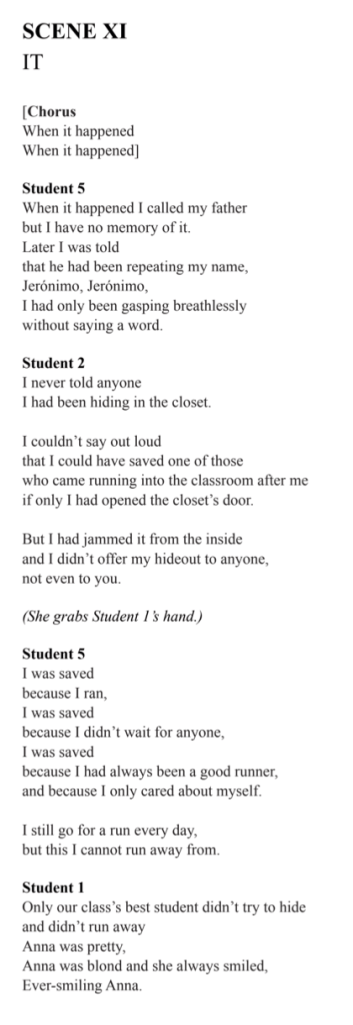

–Then listen to “IT” (Scene XI) from the opera, Innocence, by Kaija Saariaho (multilingual libretto by Aleksi Barrière of the original Finnish libretto by Sofi Oksanen) from 44.25 minutes to 49.33 minutes in the following link.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZz2bxnAQfs&lc=Ugzut1S6c6UsP2ED_vx4AaABAg

This particular scene is about a mass school killing, sung by the students and in different languages. You will want to read the English translation below before watching the clip.

–Saariaho stipulates that the Shooter should not appear on stage. The Colonial Soldier is, in contrast, the first shooter heard in Lens’s work. So what?

The opening words in Hamlet are “Who’s there?” Indeed: at center-stage, and how.

English translation of Scene XI, “IT” (from https://www.wisemusicclassical.com/work/58414/Innocence–Kaija-Saariaho/; apologies for the clumsy cut and paste below)

Other sources

Bollas, C. (2011). The Christopher Bollas Reader. Routledge: London and New York.

Caute, D. (1971). The Illusion: An essay on politics, theatre and the novel. Harper Colophon Books, New York, Evanston, San Francisco, London.

Jenkins, K. (2023). “Ontology and Oppression: Race, Gender, and Social Reality” (accessed online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UW4-VT_ZTJw)

McKeon, M. ([1987] 2002). The Origins of the English Novel, 1600–1740. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London.

Moretti, F. (2013). The Bourgeois: Between History and Literature. Verso: London and New York.

https://www.ft.com/content/ac63ae0e-227a-11ea-b8a1-584213ee7b2b

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0184767820913797

https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/18008

11 thoughts on “Sixteen short examples on how differences in genre affect the structure and substance of policy and management [4 newly added]”