I come from a profession, US policy analysis and public management, that was premised from the get-go on being interdisciplinary: not just some training in economics, but also in law, research methods and political science, among others. So, economics has always had heterodox contexts for many of us.

Over my career, economics has come under a great deal of criticism. Some economists have offered fixes and their heterodox alternatives. Below is an alternative reading of economics across nine topics from a policy analysis perspective that has never been economics alone and which seeks greater policy and management relevance in being so.

1. Rethinking opportunity costs

2. “Given market-clearing prices. . .”

3. The chop-logic of risks, trade-offs and priorities

4. Another way to put #3 is that economics and reliability are not the same precisely when the disaster is majorly economic or financial

5. Nonfungibility in supply-and-demand analysis

6. The foundational economy

7. Rethinking investment

8. Rethinking public debt

9. Rethinking capitalism

1. Opportunity costs

Start with a 1977 conversation between Nicholas Kaldor, the Cambridge economist, and his Colombian interviewer, Diego Pizano.

Kaldor asserts: “There is never a Pareto-optimal allocation of resources. There can never be one because the world is in a state of disequilibrium; new technologies keep appearing and it is not sensible to assume a timeless steady-state” (Pizano 2009). Pizano counters by saying the concept of opportunity costs still made sense, even when market conditions are dynamic and unstable. But Kaldor insists,

Well, I would accept that there are some legitimate uses of the concept of opportunity cost and it is natural that in my battle against [General Equilibrium Systems] I have concentrated on the illegitimate ones. Economics can only be seen as a medium for the “allocation of scarce means between alternative uses” in the consideration of short run problems where the framework of social organization and the distribution of available resources can be treated as given as heritage of the past, and current decisions on future developments have no impact whatsoever. (Ibid)

Consider the scorpion’s sting in the last clause. Even if one admitted uncertainty into the present as a function of the past, a dollar spent now on this option in light of that current alternative could still have no impact on the allocation of resources for a future that is ahead of us.

Why? Because markets generate resources and options, not just allocate pre-existing resources over pre-existing alternatives. “Economic theory went astray,” Kaldor adds, “when theoreticians focused their attention on the allocative functions of markets to the exclusive of their creative functions, which are far more important since they serve as an instrument for transmitting economic changes”.

I want to draw your attention for what follows to the importance of real-time generation of resources and options. Improvisations, at least in real time, have no “pre-existing” alternative and in that way no opportunity cost as conventionally understood. There is no workaround for improvisation.

2. “Given market-clearing prices. . .”

Speaking of convention, how many times have we heard something like, “Given the right incentives,,,,” “If implemented as planned…,” or “Given market-clearing prices…”? Just like that older version: “Monarchy is the best form of government, provided the monarch possesses virtue and wisdom.”

“If implemented as planned,” when we know that is precisely the assumption we cannot make in the face of unpredicted contingencies. (Why else the need for improvisation?) “Given the right incentives,” when we know that “right” is unethical without specifying what the case before us is. “Given market-clearing prices,” when we know not only that actually-existing markets often do not clear (supply and demand do not equate at a single price)–and even when they do, their “efficiencies” can undermine the reliability of the very markets that produce those prices.

3. The chop-logic of risks, trade-offs and priorities

Take any major policy issue–an economic emergency or financial crisis. Immediately, the talk becomes one about the risks and trade-offs involved, and the priorities called for

when both are taken into account. This chop-logic—-when it comes to economics and policy writ large, identify the risks, look for trade-offs, and then set priorities—is so naturalized as to be taken for granted and treated as preknown.

But the chop-logic is to be questioned in cases of critical infrastructure emergencies having major economic and financial consequences. There are at least three sets of empirical reasons for this:

(1) Empirically, yes major critical infrastructures – like those for electricity, water, and telecoms – operate under budget and personnel constraints. Obviously then, risks, trade-offs and priorities surface and at times take center stage when path dependencies are as extended as in society’s critical infrastructures.

Even so, there is a point at which infrastructure centralized control rooms (if present) will not trade-off systemwide reliability in service provision—that is, the safe and continuous provision of the service, even during (especially during) turbulent times—for, say, cost reductions or labor savings. Why? Because when the electricity grid islands, people die; people. Preventing disasters, more routinely than not, is what highly reliable infrastructures do.

(2) Empirically, when a catastrophe happens, the pressing logic and urgency of immediate emergency response have been repeatedly demonstrated, namely: Restore electricity, water supplies, telecoms, and roads, right now. Improvisations and ingenuity, jointly undertaken and shared, move center stage. In fact, there is no better acknowledgement of the importance and centrality of vital service infrastructures than the self-evident necessity of restoring backbone

services as soon as possible when their usual infrastructure operations fail.

(3) Empirically, yes, risks, trade-offs and priorities also move center stage in longer-term recovery after economically important infrastructures fail, but only to the extent high reliability in service provision has yet to be restored to (a new) normal for the (sometimes replaced) infrastructures. Typically, analysis and deliberation during economically significant recovery are far messier than “the risks, trade-offs, and priorities with respect to flood recovery are the obvious center of attention” (for more, see Roe 2013, 2020, 2023).

4. Another way to put #3 is economics and reliability are not the same precisely when the disaster is majorly economic or financial.

Economics assumes substitutability, where goods and services have alternatives in the marketplace; infrastructure high reliability (which includes systemwide safety) assumes practices for ensuring nonfungibility, where nothing can substitute for the high reliability of critical infrastructures without which there would be no markets for goods and services, right now when selecting among those alternative goods and services or generating them anew (as in improvising). There is a point at which nonfungible high reliability and fungible trade-offs are immiscible, like trying to mix oil and water (Roe and Schulman 2008, 2016).

One way of thinking about the nonfungibility of infrastructure high reliability is that it’s irrecuperable economically in real time. The safe and continuous provision of a critical service, even during (especially during) turbulent times, cannot be cashed out in dollars and cents and be paid to you instead of the service.

5. Nonfungibility in supply-and-demand analysis

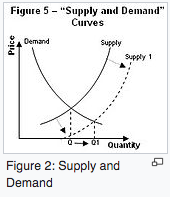

Take the conventional supply and demand curves, like the one below from Wikipedia:

That is: assume demand and supply curves intersect with equilibrium price P* and quantity Q. Now the thought experiment: At some point, say the supply curve shifts downwards and intersects with the horizontal axis (as with the dotted Supply 1 curve in the figure).

When so, then at that point, there is a quantity supplied even when price is zero. To put it another way, a portion of the quantity demanded is actually provided at no price because, say, suppliers are confused, or everyone got just lucky, or, as I suggest, highly reliable supply is non-fungible up to the intersection point.

6. The foundational economy

I

An AI-generated definition is good-enough to start: “The ‘foundational economy’ (FE) is the infrastructure of everyday life, including essential services like water, electricity, healthcare, and housing, that are required for society to function.” (The key website is The Foundational Economy.) Even at that level of abstraction, it’s clear there is no one and only FE with one and only one set of critical infrastructures in each.

How so?

II

Here are ten propositions by way of answer:

(1) By definition, a foundational economy would not exist if it were not for the reliable provision of electricity, water, telecoms, and transportation. Here again reliability means the safe and continuous provision of the critical service in question, even during (especially during) turbulent times. This means, for example, that the physical systems as actually managed and interconnected on the ground establish the spatial limits of the FE in question.

(2) By extension, no markets for goods and services in the FE would exist without critical infrastructure reliability supporting their operations. This applies to rural landscapes as well as urban ones.

(3) Other infrastructures, including reliable contract and property law, are required for the creation and support of these markets, though this too varies by context. One can, for example, argue healthcare and education are among the other infrastructural prerequisites for many FEs (as above).

(4) Preventing disasters in the face of existing and prospective uncertainties is what highly reliable infrastructures do. Why? Because, to reiterate the point made in #3, when the electricity grid islands, the water supplies cease, and transportation grinds to a halt, then people die and the foundational economy seizes up (Martynovich et al. 2022).

(5) Another way to say this is that within a foundational economy you see clearest the tensions between economic transactions and reliability management mentioned earlier. To repeat, economics assumes substitutability, where goods and services have alternatives in the marketplace; infrastructure reliability assumes practices for ensuring nonfungibility, where nothing can substitute for the high reliability of critical infrastructures without which there would be no markets for goods and services, right now when selecting among those alternative goods and services.

(6) Which is to say, if you were to enter the market and arbitrage a price for high reliability of critical infrastructures, the market transactions would be such that you can never be sure you’re getting what you thought you were buying.

(7) This in turn means there are two very different standards of “economic reliability.” The retrospective standard holds that the foundational economy–or any economy for that matter–is performing reliably when there have been no major shocks or disruptions from the last time to now. The prospective standard holds that the economy is reliable only until the next major shock, where collective dread of that shock is why those networks of infrastructure professionals try to manage to prevent or otherwise attenuate it (Roe and Schulman 2016). The fact that past droughts have harmed the foundational economy in no way implies people are not managing prospectively to prevent future consequences of drought on their respective FEs–and actually accomplishing that feat.

(8) Why does the difference between the two standards matter? In practical terms, the foundational economy is prospectively only as reliable as its critical infrastructures are reliable, right now when it matters for, say, economic productivity or societal sustainability. Indeed, if the latter were equated only with recognizing and capitalizing on retrospective patterns and trends, economic policymakers and managers in the FE could never be reliable prospectively in the Anthropocene.

(9) For example, the statement by two well-known economists, “Our contention, therefore, following many others, is that, despite its flaws, the best guide to what the rate of return will be in the future is what it has been in the past” (Riley and Brenner 2025) may be true as far as it goes, but it in no way offers a prospective standard of high reliability in the foundational economy (let alone other economies).

(10) So what? A retrospective orientation to where the economy is today is to examine economic and financial patterns and trends since, say, the 2008 financial crisis; a prospective standard would be to ensure that–at a minimum–the 2008 financial recovery could be replicated, if not bettered, for the next global financial crisis. Could the latter be said of the FE in your city, metropolitan area or across the rural landscape of interest?

7. Rethinking investment

“Therefore, infrastructure and connectivity, rather than trade and investment, should be the focus in order to understand the specific character of any Chinese sphere of influence among the Mekong states.” (Greg Raymond 2021. Jagged Sphere: China’s Quest for Instructure and Influence in Mainland Southeast Asia. Lowy Institute: Sidney Australia accessed online at https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/RAYMOND%20China%20Infrastructure%20Sphere%20of%20Influence%20COMPLETE%20PDF.pdf)

“What is the first act that creates the economy? It is neither production nor exchange (market or otherwise). It is the storing of wealth over time, with which I associate with investment.” (Daniel Judt 2025. “Storage, Investment, and Desire: An interview with Jonathan Levy,” Journal of the History of Ideas Blog accessed online at https://www.jhiblog.org/2025/02/24/storage-investment-and-desire-an-interview-with-jonathan-levy/)

I

Greg Raymond makes a convincing case for his epigraph point and I too among many emphasize, as above, the centrality of infrastructures and their interconnectivities in underwriting economies and the maintenance of market transactions.

The point here in #7, however, starts with the argument of economist, Jonathan Levy, in his recent The Real Economy: Contrary to conventional economics with its fulcrum of allocation and exchange, it is investment which creates economies. Real-time improvisations may have no formal opportunity costs, but they are most decidedly an investment in the infrastructures concerned.

Thinking infrastructurally about investment highlights three under-recognized insights that are highly policy relevant.

II

First, investments import the long run into infrastructure analysis in ways that a focus on allocation and exchange do not. These ways range from the banal—it takes time for the infrastructure to be planned, funded, implemented and then operated as constructed and managed—to more invisible considerations.

The pressures to innovate technologies, in particular, means that some infrastructure technologies (software and hardware) are rendered obsolete before the infrastructures have been fully depreciated. This brings uncertainty into investing in technology and engineering of infrastructures that can last ahead, say, two generations or more. Here, the long run means another short-run, and those short-runs at times can look like boom and busts, well away from anything like “infrastructure full capacity.”

And yet, second, there are examples of infrastructures being operated beyond their depreciation cycles. Patches, workarounds and fixes–many improvised–keep the infrastructure in operation, even if that reliability is achieved at less than always-full capacity. It takes professionals inside the infrastructure to operationally redesign technologies (and defective regulations) so as to maintain critical service provision reliably during the turbulent periods of exogenous and endogenous change.

Third, while this professional ability to operationally redesign systems and technologies on the fly and in real time in effect extend reliable operations, the actual workarounds and fixes are often rendered invisible under the bland catch-all, “infrastructure maintenance and repair,” where even improvised operations become part and parcel of corrective maintenance.

The latter means, however—and this is the key point here—that maintenance and repair are far from being bland and worthy only of passing mention. Really-existing maintenance and repair and their personnel are in fact the core investment strategy for longer term reliable operations of infrastructures faced with uncertainties induced from the outside (e.g., those external shocks and surprises over the infrastructure’s lifecycle) and from the inside (e.g., those premature engineering innovations).

III

So what?

Since the 2007/2008 financial crisis, we’ve heard and read a great deal about the need for what are called macroprudential policies to ensure interconnected economic stability in the face of globalized and interconnected challenges, ranging from defective international banking to the climate emergency. These calls have resulted in, e.g., massive QE (quantitative easing) injections by central banks and massive new infrastructure construction initiatives by the likes of the EU, the PRC, and the US.

What we haven’t seen are comparable increases in the operational maintenance and repair of critical infrastructures necessary for functioning economies and supply chains, let alone for “economic stability.” Nor have we seen in the subsequent formal investments in science, technology and engineering anything like a comparable creation and funding of national academies for the high reliability management of those backbone critical infrastructures. Few if any are imagining national and international institutes, whose new funding would not be primarily directed to innovation as if it were basic science, but rather to applied research and practices for enhanced maintenance and repair, innovation prototyping, and proof for scaling up.

In sum, if I am right in thinking of longer-term reliability of backbone infrastructures as the resilience of an economy that is undergoing shocks and surprises, then infrastructure maintenance and repair–and their innovations–move center stage in ways not yet appreciated by politicians, policymakers and the private sector.

8. Rethinking public debt

I

If I am reading historians Istvan Hont and Michael Sonenscher correctly, 18th century thinkers wrestled again and again with the constitutional means for reining in the bad-side of public debt (e.g., rulers use the monies for war), while promoting the good-side (e.g., rulers build the infrastructure Adam Smith himself saw necessary for human betterment).

Today, what to do about the public debt is even further from being reconciled, at least as a matter of an economics that is reliability-seeking. Constitutional proposals to ensure balanced budgets have come and gone; actual constitutional amendments, e.g. Germany’s restricting budget deficits to no greater than a certain percent of GDP, are suspended or circumvented. Green golden rules are proposed today that “would exclude any increase in net green public investment from the fiscal indicators used to measure compliance with fiscal rules,” recognizing however that “by allowing green spending to be financed by borrowing. . .could undermine public debt sustainability”. Etc. Etc.

In fact, nations now divide into two with respect to public debt: those that kick their public debt bucket down the road and those finding it more and more difficult to do so. ““This idea that we can continue to kick the can down the road” is no longer tenable,” [an expert recently put it about this debt]. “That horizon is coming very much closer to us.”” (https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/473151/sovereign-debt-crisis-wall-strwet) Even closer when you add the increasing pressure on governments to pick up private-sector pensions commitments that can’t be met.

What to do?

II

One answer is to recast the public debt. Infrastructurally, think of public debts like keystone ecosystems, the way groundwater systems are central to other dependent terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Or that public debts are the infrastructures experienced as the social property of the propertyless, who know best when and how to depreciate their assets. If the public debt is our ruination, then we have to push that point further to how public debts are experienced, here and now.

III

This experience of public debt in real time is the perfect place to start reframing. Begin with one of the most recent cases, the 2020 Zambia government default:

Zambia defaulted on interest payments to some of its private lenders in November 2020 when private creditors refused to suspend debt payments. In February 2021, Zambia applied for a debt restructuring through the Common Framework, but little progress has been made on the negotiations as large private creditors, such as BlackRock, have so far refused to reach an agreement on debt relief.

BlackRock, headed up by Larry Fink, is the largest of a number of bondholders who are refusing to cancel Zambia’s debt, despite lending to a country with interest rates as high as 9% (in comparison to wealthy countries like Germany, UK and USA who were given loans at 0-2% interest in the same time period) potentially making huge profits. Debt Justice estimates that BlackRock could make up to 110% profit if repaid in full.

Meanwhile, Zambia is experiencing devastating impacts of the climate crisis such as flooding, extreme temperatures and droughts, which are causing significant disruption to livelihoods and severe food insecurity. Unsustainable debt levels mean the country lacks many of the resources required to address these impacts. This decade, Zambia is due to spend over four times more on debt payments than on addressing the impacts of the climate crisis.

It should be noted that compared to BlackRock, only two nations, the USA and PRC, have GDPs greater than the wealth managed by BlackRock (whose recent assets are reported to be well over $10 trillion). It’s also reported that the ten largest asset-management firms together manage some $44 trillion, roughly equivalent to the annual GDPs of the USA, PRC, Japan and Germany.

That said, yes of course, we still must say that this and other current sovereign debt crises could be better managed by the governments concerned. Fair enough.

But it would be more accurate to say that BlackRock is actually being managed in ways that nations can’t manage sovereign debt, i.e., BlackRock has a C-suite nations don’t have. Why then not start with BlackRock as the catalyst for better management? (After all, it rose to an undisputed shareholder superpower only after the last financial crisis of 2008.)

Or from the other direction, think of BlackRock as the global financial crisis underway and the “sovereign debt crisis” as the smoke-and-mirrors to get the rest of us to believe otherwise. We know exactly who benefits from placing the blame on the Government of Zambia’s fiscal and monetary management, when the global behemoth BlackRock is managed even worse in terms of self-interest.

IV

Consider another example of how to reframe the public debt (or at least the experience of that debt): off-budget items as a way of funding that can’t be financed through public debt:

The EU cannot finance its budget through debt, but the EU Treaties do not prohibit the issuance of EU-27-backed securities or bonds for off-budget operations, as long as they are approved by the Council. The largest collective borrowing operation in EU history so far was the temporary Covid-19 recovery program NextGenerationEU (NGEU), which received 90 per cent of its financing through the Recovery and Resilience Fund (RRF) for which the European Commission borrowed €807 billion on behalf of the EU-27 by issuing green bonds. NGEU presents itself as a green industrial investment program for the benefit of future generations, but it is pervaded by a fundamental contradiction: the repayment involves an intergenerational debt transfer, burdening future generations with €30 billion in annual debt servicing , starting in 2028 and ending in 2058.

Angela Wigger (2025). “Behind InvestEU’s Trojan Logic: Public Guarantees, Private Gains, and the Illusion of Climate Action,” accessed online at https://www.nl/behind-investeus-trojan-logic/

Here focus on the bolded terms: off-budget operations and intergenerational debt transfer.

Once upon a time, the basic idea of a budget was to be comprehensive. There’s nothing “off-budget” if the objective is constrained maximization of system benefits net of expenses. Of course, that hasn’t stopped all manner of moves to sequester below-line expenses as if they weren’t subject to budget constraints:

Technocrats’ creative reinterpretation of their own authority and governments’ creative fiscal accounting via off-budget financing vehicles can improve fiscal-monetary coordination and create significant fiscal space (van ’t Klooster, 2022; Guter-Sandu and Murau, 2022). However, the hidden and interim nature of these solutions preempts. . .

(accessed online at https://scispace.com/pdf/green-macrofinancial-regimes-2o45dbuoim.pdf)

Article titles, like “The Eurozone’s Evolving Fiscal Ecosystem: Mitigating Fiscal Discipline by Governing Through Off-Balance-Sheet Fiscal Agencies,” give the game away.

Moreover, the increasingly out-of-date riposte no longer works, namely: Future generations will have more income than we do to cover these debts. We’re in times of decreasing per-capita incomes and near-zero discount rates, where the generations ahead are to be treated just as alive as we are. If you agree with the latter, then note also that the wider declension narratives at work—apocalypse, catastrophe, polycrisis—undermine the very persistence of concepts, like government budgets, intergenerational debt and “future generations.”

So, again, what’s to be done? Again, start by reframing. What life-worlds already exist that do not rely on these terms, budgets, debt and generations; apocalypse, catastrophe and polycrisis? That is, in addition to the always-on search for alternative social movements, we are looking for those breaches in political economies and heterogeneities that displace, re-situate or unaccent the terms that now leave us nowhere else to go.

V

“Breaches and heterogeneities”? That level of analysis requires us to be more granular than appeal to abstract levels of this or that political economy. For example, it’s not varieties of capitalism (or anti-capitalism for that matter) we are looking for but rather specific hybrids and subsystems. Let’s take the example of free ports as illustrative.

The instance of free ports would seem to take us right back to the heart of capitalism, with its Special Economic Zones (SEZ) and such. But we would be wrong. The authors of a recent global study of free ports, Koen Stapelbroek and Corey Tazzara (2023), stress their own version of “off-balance sheet”. “Free ports offered essential services that the prevailing system of political economy scarcely allowed.” More specifically:

Rather than treating free ports as intrinsically liberal or illiberal, it is better to see them as controlled breaches in the prevailing political economy, whether that be of a state or of an entire trading system. With respect to national political economy the breach is obvious, since by definition a free port policy entailed a relaxation of ordinary controls over trade and often other parameters such as immigration. The extent of control varied for reasons ranging from technology to the fiscal trade-offs unavoidable in any customs policy. The underlying strategy varied, too – in some cases, free ports served to stabilise a state’s political economy (as in Genoa), in other cases as a forerunner to transform the interior economy (as in the Caribbean). The free port shows that the modern state has never endorsed homogeneous space: there have always been breaches, sometimes of great importance.

Koen Stapelbroek & Corey Tazzara (2023) The Global History of the Free Port, Global Intellectual History, 8:6, 661-699, DOI: 10.1080/23801883.2023.2280091

So what? What does this mean practically?

Consider the familiar recommendation: “Suspend and cancel debt payments when a climate extreme event takes place, so countries have the resources they need for emergency response and reconstruction without going into more debt.” This statement has no semantic meaning for really-existing policy and management in the absence of drawing conclusions from the run of diverse cases of “extreme events,” including but not limited to equally granular cases of free ports. At a minimum, this means capitalism is far far more complicated, granularly.

9. Rethinking capitalism

(1) What does anti-capitalist actually mean these days?

Ending capitalism isn’t just hard to realize; it’s hard to theorize and operationalize. That is: “Under capitalism” means that even in always-late capitalism, we have

laissez-faire capitalism, monopoly capitalism, oligarchic capitalism, state-guided capitalism, party-state capitalism, corporate capitalism, corporate-consumerist capitalism, bourgeois capitalism, patrimonial capitalism, digital capitalism, financialized capitalism, political capitalism, social (democratic) capitalism, neoliberal capitalism, crony capitalism, cannibal capitalism, wellness capitalism, petty capitalism, platform capitalism, cloud capitalism, surveillance capitalism, infrastructural capitalism, algorithmic capitalism, welfare capitalism, authoritarian capitalism, imperialistic capitalism, turbo-capitalism, post-IP capitalism, green (also red and brown) capitalism, climate capitalism, extractive capitalism, libidinal capitalism, clickbait capitalism, emotional (affective) capitalism, tech capitalism, American capitalism, British capitalism, European capitalism, Western capitalism, transnational capitalism, global capitalism, agrarian capitalism, disaster capitalism, rentier capitalism, industrial capitalism, post-industrial capitalism, fossil capitalism, settler-colonial capitalism, supply chain capitalism, asset manager capitalism, information (data) capitalism, cyber-capitalism, cybernetic capitalism, racial capitalism, necro-capitalism, bio-capitalism, war capitalism, crisis capitalism, managerial capitalism, stakeholder capitalism, techno(scientific)-capitalism, pandemic capitalism, caring capitalism, zombie capitalism. . .

Oh hell, just stop there. Much of this proliferation looks like classic product differentiation in competitive markets. In this case: by careerists seeking to (re)brand their lines of inquiry for a competitive advantage in professions that act more and more like markets anyway.

Now, of course, it’s methodologically positive to be able to differentiate types and varieties of capitalism, so as to identify patterns and practices (if any) across the diversity of cases. But how is the latter identification to be achieved with respect to a list—namely the above—without number?

Or from the other direction, some of the terms do seek to denote specific contexts and levels of granularity and commonalities across cases. But, as others do not, what then does being “anti-capitalist” actually mean?

(2) One answer: Anti-capitalism depends on taking the losers in any such list seriously.

Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel economist, confirms: “Only around half of Americans born after 1980 could hope to have earnings higher than their parents (down from 90 percent for the cohort born in 1940).” But even if true, is the implication that at least some of the capitalisms listed above were “better” then than now?

For example, pathologies arising from increased financialization have been “blamed on the disappearance of capitalism in its classical form, with the latter now painted in retrospect as a system in which market logics led to productive investment, more-or-less shared growth and functional politics.” But haven’t we always been told capitalism is bad? Didn’t many of our parents and grandparents suffer under conditions of capitalism all along just as we are?

Yet any such conclusion leads to an obvious question: What if the seriatim crises of capitalism are treated as proof-positive not of “its” death rattle but of the vitality in morphing through losers after losers after losers? That is, it’s the losers in the above list that first need to be differentiated and tracked.

(3) The upshot: Superfluidity of terms in #(1) hides a superfluidity of capitalisms’ losers in #(2).

So what? Well, for one thing, Hicks-Kaldor can finally take its last breath.

According to the Hicks-Kaldor compensation principle, it’s good enough when an economic change means its winners would be better off even if they could compensate the losers of this change. The notion that actual compensation does not need to take place over the course of this now very long history of differing losers and differing losses is now even more ludicrous than before. Indeed, to be anti-capitalist is today to be anti anything like an abstracting Hicks-Kaldor. What then should we be saying about winners and losers, at least those who are right now in real time? I prefer this:

We cannot even imagine a happy world in which winners might not be hateful. Only in those who lose do we feel we might recognise fellow human beings, because if we call them unlucky, downtrodden victims, at least in the present moment we can be certain that we are not mistaken. (Natalia Ginsburg, 1970, accessed online at https://www.equator.org/articles/our-monstrous-ideas-natalia-ginzburg)

Other sources

Darvas, Z. (2022) “Legal options for a green golden rule in the European Union’s fiscal

framework.” Policy Contribution 13/2022, Bruegel (accessed online at https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/PC%2013%202022.pdf)

Dyk, Silke van and M. Kip (2023). “Rethinking social rights as social property: alternatives to private property, and the democratisation of public politics.” Critical Sociology (accessed online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/08969205231195378)

Hont, I. (2005). Jealousy of Trade. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

Johnson, N. (2023). “Times of interest: longue-durée rates and capitalist stabilization.” (accessed online at https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii143/articles/nic-johnson-times-of-interest)

Mammola, S. et al (2023). “Groundwater is a hidden global keystone ecosystem.” Global Change Biology (accessed online at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.17066)

Martynovich, M., T. Hansen, and K-J Lundquist (2022). “Can foundational economy save regions in crisis?” Journal of Economic Geography, 1–23 (https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbac027)

Paprocki, K. (2022). “Anticipatory ruination.” The Journal of Peasant Studies (accessed online at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03066150.2022.2113068)

Pizano, D. (2009). Conversations with Great Economists. New York: Jorge Pinto.

Riley, D. and R. Brenner (2025). “The long downturn and its political results: a reply to critics.” New Left Review 155, 25–70 (https://newleftreview.org/?pc=1711)

Roe, E. (2013). Making the Most of Mess: Reliability and policy in today’s management challenges. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

———- (2020). A New Policy Narrative for Pastoralism? Pastoralists as Reliability Professionals and Pastoralist Systems as Infrastructure, STEPS Working Paper 113, Brighton: STEPS Centre

———- (2023). When Complex is as Simple as it Gets: Guide for Recasting Policy and Management in the Anthropocene. IDS Working Paper 589, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, DOI: 10.19088/IDS.2023.025

Roe, E. and P.R. Schulman (2008) High Reliability Management, Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

——- (2016). Reliability and Risk, Stanford CA: Stanford University Press.

Sonenscher, M. (2007). Before the Deluge: Public Debt, Inequality, and the Intellectual Origins of the French Revolution. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ.

Vallée, S. (2023). “Germany has narrowly swerved budget disaster – but its debt taboo still threatens Europe.” (accessed online at https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/dec/13/germany-budget-debt-europe-constitution-crisis).

2 thoughts on “What you get when economics is too important to leave to the economists: one recasting for increased policy and management relevance”