—When it comes to pastoralists, I have in mind. . .

—Traditional mixed agriculture as reliability-seeking, not risk-averting

—The computational irrationality of The Tragedy of the Commons

—Colin Strang or Garrett Hardin: Which one do you believe?

—Frustrated herders

—Reframing the latest drought in East Africa

—Borana sedentarization

—Which “rangeland restoration”?

—Environmental livestock-tarring

—Rethinking early warnings for drought

—“Curating publics,” not just “facilitating development”

—A different lens to recast pastoralist mobility: “logistical power from below”

—“Adaptable” and “flexible” are not nuanced enough to catch the place-specific nature of pastoralist improvisations

—Pastoralists as social figures

—Dust and herders viewed from the paradigm of repair (newly added)

When it comes to pastoralists, I have in mind. . .

I have in mind those who regret the passing of pastoralism as if it were a singular institution with its own telos, agency and life-world. It wasn’t and it isn’t. When was the last time these people asked herders their party affiliation? When was the last time they really treated the pastoralist as neoliberal citizen?

These commentators are like the freshwater biologists who consider Lethenteron appendix (the American brook lamprey) and Triops cancriformis (a type of tadpole shrimp) to be evolutionary success stories because the organisms haven’t evolved. By this measure, the best pastoralists are like feisty little tardigrades, those near-microscopic (another “marginal”!) organisms that survive in the most hostile environments on the planet.

I also have in mind those long-trough narratives of depastoralizing, deskilling, disorganizing and dewebbing the pastoralist life-world, leaving behind corpse-pastoralism, flogged by conflicts, mummified by inequality, buried at sea in waves of liquid modernity, dissolved by the quicklime of disaster capitalism and speculative finance, always harboring worse to come.

I have in mind the hangover notion that policy and procedure are at every turn subordinate to state power, that politicians and officials are nothing but the state’s secretariat to capitalists, that capitalisms have entirely colonized every nook and cranny of the life-worlds, and that we have surrendered our minds entirely to politics, such as they are.

I have in mind the disturbing parallel between those who want to save Planet Earth by means of straightforward treatments like stopping fossil fuel or methane-producing cattle and, on the other hand, Purdue Pharma’s promotion of OxyContin as treatment for chronic pain that masked the lethal addiction to this kind of “straightforward” medicine.

Last but not least, I have in mind the remittance-sending household member who is no more at the geographical periphery of a network whose center is an African rangeland than was Prince von Metternich in the center of Europe, when he said, “Asia begins at the Landstraße” (the outskirts of Vienna closest to the Balkans). You can stipulate Asia begins here and Africa ends there, but good luck in making that stick within and across national policies.

Methodological upshot: It cannot be said often enough that you mustn’t expect reproduction of the same even when reversion to the mean occurs.

For an introduction to elements of the interconnectivity framework, see: E. Roe and P.R. Schulman (2023). “An Interconnectivity Framework for Analyzing and Demarcating Real-Time Operations Across Critical Infrastructures and Over Time.” Safety Science (available online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2023.106308)

Traditional mixed agriculture as reliability-seeking, not risk-averting

A risk-averse farmer keeps multiple varieties of crops, livestock and/or sites so that, if one fails, s/he has others to fall back on. The more different crops, livestock and sites a farmer can muster and maintain, the greater the chances s/he won’t lose everything. Where possible, the risk-averse farmer avoids hazards whose probabilities and uncertainties cannot be managed so as to maintain a survival mix of crops, livestock and productive sites. The risk-averse farmer faces a land carrying capacity that sets exogenous limits on the total crops and livestock produced.

A reliability-seeking farmer keeps multiple varieties of crops, livestock and/or sites because any single resource—e.g., the soil that sustains the crop, site and livestock—is managed better if it provides multiple services. The more crops, livestock and sites a farmer can muster and maintain, the greater the chances s/he can meet peak demands made on his or her entire production system. The reliability-seeking farmer seeks to manage the probabilities and uncertainties of hazards that cannot be avoided so as to maintain a peak mix of crops, livestock and sites. The reliability-seeking farmer faces a carrying capacity whose endogenous limits are set by farmer skills for and experience with different operating scales and production phases.

Upshot

Farming behavior, no matter if labelled “subsistence” or “traditional,” that

- is developed around high technical competence and highly complex activities,

- requires high levels of sustained performance, oversight and flexibility,

- is continually in search of improvement,

- maintains great pressures, incentives and expectations for continuous overall production, and

- is predicated on maintaining peak (not minimum) livestock numbers in a highly reliable fashion without threatening the limits of system survival

is scarcely what one would call “risk-averse.”

The computational irrationality of The Tragedy of the Commons

Here is my rearrangement of quotes from a recent piece by philosopher, Akeel Bilgrami:

[I]t is often felt that. . .the commons is not doomed to tragedy since it can be ‘governed’ by regulation, by policing and punishing non-cooperation.

Who can be against such regulation? It is obviously a good thing. What is less obvious is whether regulation itself escapes the kind of thinking that goes into generating the tragedy of the commons in the first place. . . .

To explain why this is so, permit me the indulgence of a personal anecdote. It concerns an experience with my father. He would sometimes ask that I go for walks with him in the early morning on the beach near our home in Bombay. One day, while walking, we came across a wallet with some rupees sticking out of it. My father stopped me and said somewhat dramatically, ‘Akeel, why shouldn’t we take this?’ And I said sheepishly, though honestly, ‘I think we should take it.’

He looked irritated and said, ‘Why do you think we should take it?’ And I replied, what is surely a classic response, ‘because if we don’t take it, somebody else will’. I expected a denunciation, but his irritation passed and he said, ‘If we don’t take it, nobody else will’. I thought then that this remark had no logic to it at all. Only decades later when I was thinking of questions of alienation did I realize that his remark reflected an unalienated framework of thinking. . . .

From a detached perspective, what my father said might seem like naïve optimism about what others will do. But the assumption that others will not take the wallet if we don’t, or that others will cooperate if we do, is not made from that detached point of view. It is an assumption of a quite different sort, more in the spirit of ‘let’s see ourselves this way’, an assumption that is unselfconsciously expressive of our unalienatedness, of our being engaged with others and the world, rather than assessing, in a detached mode, the prospects of how they will behave. . . .

The question that drives the argument for the tragedy of the commons simply does not compute. . .

https://www.thephilosopher1923.org/post/what-is-alienation

To repeat: The question that drives the argument for the Tragedy of the Commons simply does not compute in such cases. In the latter, the Prisoner’s Dilemma is computationally irrational.

Colin Strang or Garrett Hardin: Which one do you believe?

M: You seem now to be in the paradoxical position of saying that if everyone evaded [e.g., paying taxes], it would be disastrous and yet no one is to blame. . . .But surely there can’t be a disaster of this kind for which no one is to blame.

D: If anyone is to blame it is the person whose job it is to circumvent evasion. If too few people vote, then it should be made illegal not to vote. If too few people volunteer, you must introduce conscription. If too many people evade taxes, you must tighten up your enforcement. My answer to your ‘If everyone did that’ is ‘Then some one had jolly well better see that they don’t’. . .

Colin Strang, philosopher, “What If Everyone Did That?”, 1960

Eight years later, we get Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Common, whose answer to “What if every herder did that?” is: “We must admit that our legal system of private property plus inheritance is unjust–but we put up with it because we are not convinced, at the moment, that anyone has invented a better system. The alternative of the commons is too horrifying to contemplate. Injustice is preferable to total ruin.”

Get real: We’ve always known the better question is: Whose job is it to ensure overgrazing doesn’t happen? Which, to be frank, continues to be the same as asking: Whose job is it to define “overgrazing”?

NB: One of the biting ironies is that Hardin’s explicit piece on morality took no account of Strang’s essay, which was among the most cited and anthologized in collections on ethics and morality at that time.

Frustrated herders

I

How is it that we outsiders can be certain about pastoralist wants and needs? One answer is that pastoralists tell us what’s what.

Another answer, the one I explore here, is when pastoralists do no such thing. Even if they say, “This is what we want and need,” there are important occasions where they are no are more omniscient about their needs and wants than are the question askers–or for that matter the rest of us.

On the upside, a continued asking and answering can clarify the respective needs and wants–even if in unpredictable or uncontrollable ways by those involved.

II

The crux is that needs and wants fit too easily in with the language game of deprivation and gratification. In this view, pastoralist needs and wants are deprivations that continue and change only for the better when gratified. Gratifying needs and wants, as such, turns into as a species of prediction, for which planning and its cognates are suitable responses.

The reality of contingency and human agency is that the future, let alone the present, is not that predictable. In this reality, peoples’ needs are more an experiment than something to be met, or not.

III

Let me sketch three of the policy and management implications:

1. First, the frequency of wants and needs being frustrated–be they pastoralist, NGO, researcher, or government–is more to the point than deprivation and gratification.

Frustration not only because needs and wants aren’t fulfilled, but also frustration over having to figure what the needs and wants “really” are. Researchers are frustrated, pastoralists are frustrated, NGO staff are frustrated, and so too government officials at times.

The good news is when learning to handle frustrations means having to think more about what works and that more thinking means better handling of the frustrations ahead. To my mind, the center of gravity around frustration highlights what’s missing in notions of “resilience in the face of uncertainty.” Handling frustrations better is about what you–you, me, pastoralist, NGO staff person, researcher, government official–do between bouncing back and bouncing forward.

2. Still, saying we must handle frustrations without becoming paralyzed or stalemated sounds a bit too pat an answer.

I’m arguing, though, that these frustrations are better appreciated when recast as the core driver of relationships between and among pastoralists, researchers, NGOs and government staff. Bluntly stated, this is how the principal sides know they are in a relationship. This is not news: People pose problems for others and when those problems are frustrating, the salience of the relationship(s) increases for the parties.

3. This is why I make it such a big issue about just who are pastoralists talking to. Are they actually frustrated with this really-existing government official or that actually-existing NGO staff person? Are they in a relationship, however, asymmetrical, or is it that others are just a nuisance for them, if that?

Is the researcher actually frustrated with the pastoralists s/he is studying and, if so, in what ways is that frustration keeping their relationship going? Here too it is important, I think, to distinguish between those skilled in riding uncertainties and allied frustrations and those whose skills in relationships are elsewhere or otherwise.

Reframing the latest drought in East Africa

Nothing in what follows argues against the latest East Africa drought being of catastrophic proportions in terms of human and livestock deaths and migrations. What I want to do here is contextualize this catastrophe differently in order to show what remains a catastrophe has some different but major policy and management implications.

I

Start with recent debates over periodizing World Wars I and II. It’s one thing to adopt the conventional periodization of the latter as 1939 – 1945. It is another thing to read in detail how 1931 – 1953 was a protracted period of conflicts and wars unfolding to and from a pivotal paroxysm in Europe.

In the latter perspective, the December 1941 – September 1945 paroxysm, with the Shoah and the Eastern front carnage, was short and embedded in a much longer series of large regional wars. These in turn were less preludes to one another than an unfolding process that was indeed worldwide. (Think: Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, the late 1940s Dutch war in Indonesia, the French war in Indochina from the late 1940s through early 1950s, and the Korean War.)

II

Now think of the latest East Africa drought as one such paroxysm, with drought-related conflicts leading up to and following from it. So what? What follows for policy and management there?

Current emergency management lingo about this or that “longer-term recovery” would be considerably problematized when the longer term is one drought unfolding into another drought and so on. Immediate emergency response would look considerably less immediate when embedded in a process of recurring response always before the next disaster.

III

What does this mean practically?

What does it mean to frame the current East Africa drought as a paroxysm that extends both the spatial and temporal terms of “recurring drought response and recovery across East Africa”?

Clearly one major issue is government budgets (in the plural) for their recurrent operations in pastoralist areas. Or more negatively, you’re looking at the recurrent cost crises of East Africa governments–which, to my mind, far too few critics analyze as they seem more fixed on the obvious failures of capital development projects and programs for pastoralists.

My own view (and I stand to be corrected) is that you have to have recurrent operating budget already in place in order to get recurring drought response and recovery more effective on the ground over time.

One of the major reasons why “recurring drought response and recovery” is better understood as a part of government’s recurrent rather than as the forefront of the capital budget is because pastoralists give ongoing priority to the real-time prevention of other disasters from happening along the way and the need for their improvisational behavior to do that.

Source

Buchanan, A. (2023). Globalizing the Second World War. Past & Present: A Journal of Historical Studies 258: 246-281.

Borana sedentarization

I

Unlike many economists of his generation or later ones, G.L.S. Shackle was preoccupied with how economic agents make real-time decisions in situations so uncertain that no one, including agents, knows the range of options and their probability distributions upon which to decide.

In response, Shackle produced an analysis based on possibilities rather than probabilities and what is desirable or undesirable rather than what is optimal or feasible.

For Shackle, possibility is the inverse of surprise (the greater an agent’s disbelief that something will happen, the less possible it is from their perspective). Understanding what is possible depends on the agents thinking about what they find surprising, namely, identifying what one would take to be counter-expected or unexpected events that could arise from or be associated with the decision in question. Once they think through these alternative or rival scenarios, the agents should be better able to ascribe to each how (more or less) desirable or undesirable a possibility it is.

These dimensions of possibility (possible to not possible) and desiredness (desirable to undesirable) form the four cells of a Shackle analysis, in which the agents (think: decisionmakers) position the perceived rival options. Their challenge is to identify under what conditions, if any, the more undesirable-but-possible options and/or the more desirable-but-not-possible options could become both desirable and possible. In doing so, they seek to better underwrite and stabilize the assumptions for their decisionmaking.

II

Let’s move now from the simplifications to a complexifying example. Consider the following conclusion from an investigation of sedentarization among Borana pastoralists:

Although in the case of this study we can speculate generally about what has prompted the sedentarization adaptation from quantitative analysis and the narratives of local residents, we do not sufficiently understand the specific institutions and information that individuals, households, and communities have utilized in their adaptation decision making. Only in understanding the mechanisms of such inter-scale adaptations can national and state governments work toward increasing community agency and promoting effective and efficient local adaptive capacity.

https://doi.org/10.5751/ ES-13503-270339

Such an admission is much needed in the policy and management research with which I am familiar. Thus the point made below should not be considered a criticism of the case study findings. Here I want to use the Shackle analysis to push their conclusion further.

III

Briefly stated, what and where are now undesirable adaptations in Ethiopian pastoralist sedentarization–by government? by communities? by others?–that: were not possible then and there but are now; or were possible then and there but are not now? More pointedly, where else in Ethiopia, if at all, are conditions such that those undesirable adaptations of sedentarization are now considered more desirable by pastoralist communities themselves?

If there is even one case of a community where the undesirable has now become desirable and where the now-desired is (still) possible, then sedentarization is not a matter of, well, settled knowledge.

Which “rangeland restoration”?

I

“Restore” is a big word in infrastructure studies. It’s been applied to: (1) interrupted service provision restored back to normal infrastructure operations; (2) services initially restored after the massive failure of infrastructure assets; and (3) key equipment or facilities restored after a non-routine “outage” as part of regular maintenance and repair:

–An ice storm passes through, leading to a temporary closure of a section of the road system. Detours may be possible until the affected roadways are restored. This is an example of #1.

–An earthquake hits, systemwide telecommunications fail outright big time, and mobile cell towers are brought in by way of immediate response to restore telecom services, at least initially. This is an example #2.

–A generator in a power plant trips offline. Repairs are undertaken, often involving manual, hands-on work so as to restore back on line. This kind of sudden outage happens all the time and is considered part of the electric utility’s standard-normal M&R (maintenance and repair). This is an example of #3.

II

Now think of “rangeland restoration” in these terms of 1 – 3, e.g.:

#1: Stall feeding, which is here part of normal operations, is restored after an unexpected interruption in its version of a supply chain. Trucking of water and livestock, which are also part of normal livestock operations there, are temporarily interrupted.

#2: Grasslands have been appropriated for other uses (the infamous agriculture), requiring indefinite use of alternative livestock feed and grazing until a better solution is found.

#3: A grassland fire—lightning strikes are a common enough occurrence though unevenly distributed—takes part of the grasslands out of use, at least until the next rains. Herders respond by reverting to more intensive alternative intensive grazing practices for what’s left to work with.

III

So what? Here’s one implication: the issue of overgrazing is often a sideshow distracting from what is actually going on infrastructurally. Because normal operations—remember, it’s the benchmark used here for comparisons—always has had overgrazing in its operations.

What, for example, do you think the sacrifice grazing around a livestock borehole is about? There is nothing to “restore” the immediate perimeter of this borehole back to. In fact, that “overgrazed perimeter” is an asset in normal operations of the livestock production and livelihood systems I have in mind.

Again, so what?

As I read them, calls for “rangeland restoration” are a contradiction in infrastructure parlance, namely: “rangeland recovery back to an old normal.” Recovery in infrastructure terms is a massively complex, longer term, multi-stakeholder activity without any guarantees following on immediate emergency response to outright full system collapse.

Environmental livestock-tarring

A modest proposal:

Assume livestock are toxic weapons that must be renounced in the name of climate change. Like nuclear weapons, they pose such a global threat that nations sign the Livestock Non-Proliferation Treaty (LNPT). It’s to rollback, relinquish or abolish livestock, analogous to the Non Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Treaty.

How then would the LNPT be implemented, i.e., what are the ways to reduce these toxic stockpiles of dangerous animals?

–If the history of the nuclear proliferation treaty is our guide, the livestock elimination focus quickly becomes the feasibility and desirability of particular elimination scenarios. Scenarios in the plural because context matters, e.g., the way South Africa renounced nuclear weapons could not be the same ways Belarus and Ukraine relinquished them, etc.

So assume livestock elimination scenarios are just as differentiated. We would expect reductions in different types of intensive livestock production to be among the first priority scenarios under LNPT. After that, extensive livestock systems would be expected to have different rollback scenarios as well. For example, we would expect livestock to remain where they have proven climate-positive impacts: Livestock are shown also to promote biodiversity, and/or serve as better fire management, and/or establish food sovereignty, and/or enable off-rangeland employment of those who would have herded livestock instead, etc.

–In other words, we would expect livestock scenarios that are already found empirically widespread.

Which raises the important question: Wouldn’t the LNPT put us right back to where we are anyway with respect to livestock?

–Finallly, in case there is any doubt about the high disesteem in which I hold the notion of a LNPT, let me be clear:

If corporate greenwashing is, as one definition has it, “an umbrella term for a variety of misleading communications and practices that intentionally or not, induce false positive perceptions of a system’s environmental performance,” then environmental livestock-tarring is “an umbrella term for a variety of misleading communications and practices that intentionally or not, induce false negative perceptions of a system’s environmental performance with respect to livestock.”

Source: For one of many examples of environmental livestock-tarring, see https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/nov/12/replace-animal-farms-micro-organism-rewilding-food-precision-fermentation-emissions

Rethinking early warnings for drought

Bells were increasingly used not only to summon people to church, but also to provide another prompt for a belief act to those laity who had not attended: the major bells were to be rung during the Mass at the moment of consecration of the Host, and from the late twelfth century onwards we find texts calling upon lay people to kneel and adore where ever they were at that moment…

John Arnold (2023). Believing in belief: Gibbon, Latour and the social history of religion. Past & Present, 260(1): 236–268. (https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtac012)

I

I suggest that early warnings promulgated as part of official drought management systems are designed to be bells in just the above sense: People are to demonstrate their belief in the warnings when warned. They are to take action then and there because of them.

But, as Arnold also reminds us, demonstration of obedience always entails the possibility of failure. Obeying might not work. Heeding the warning might not have been effective anyway.

Indeed, some early warning systems are designed to fail because they are also meant for non-believers. The latter include those who subscribe to other types of warnings (e.g., https://pastres.org/2023/05/12/local-early-warning-systems-predicting-the-future-when-things-are-so-uncertain/).

This matters because the stakes are high when it comes to drought for both believers and non-believers. How so?

II

It is important to understand the conditions under which the designers themselves don’t believe in their own bell-ringing systems. In their article, “Drought Management Norms: Is the Middle East and North Africa Region Managing Risks or Crises?,” Jedd et al (2021) examine the efficacy official systems in the MENA region. They conclude:

Drought monitoring data were often treated as proprietary information by the producing agencies; interagency sharing, let alone wider publication, was rare. Government officials described the following reasons for this approach. First, it could create pressure on decision-makers to take action (politicizes the issue). Second, intervention measures are costly, and so, taking measures creates strong and competing demands for financial resources from agencies and/or ministers (increase political transaction costs). Therefore, given existing policies and institutions in the countries, it is unclear to what extent drought decision-making processes would be improved or expedited with increased transparency of monitoring information. . . .

This creates a difficult puzzle: In order to mitigate future drought losses, a clear depiction of current conditions must be made publicly available. However, publishing these data may require that agencies take on the burden of allocating relief if the release of this very information coincides with a future drought crisis.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1070496520960204

III

So then the obvious policy and management question is: When it comes to the efficacy of early warnings for droughts, who do you want to start with: the believers or the non-believers?

“Curating publics,” not just facilitating development

I

You’ve done all that research on livestock herders. You’ve collected so much information to better government policy and management. You know all the critiques of big-D development. But no one is listening. No one is acting on the findings and insights.

What do you do now and instead, whoever is listening or not? One answer: undertake the practice of curating publics as a part of your work.

I am suggesting that practices–subaltern, “development,” really-existing–can be curated so as to create new publics or, better yet, counterpublics. We want them collected and illustrated in ways that stick in these peoples’ minds, regardless of the dominant development narratives already there.

II

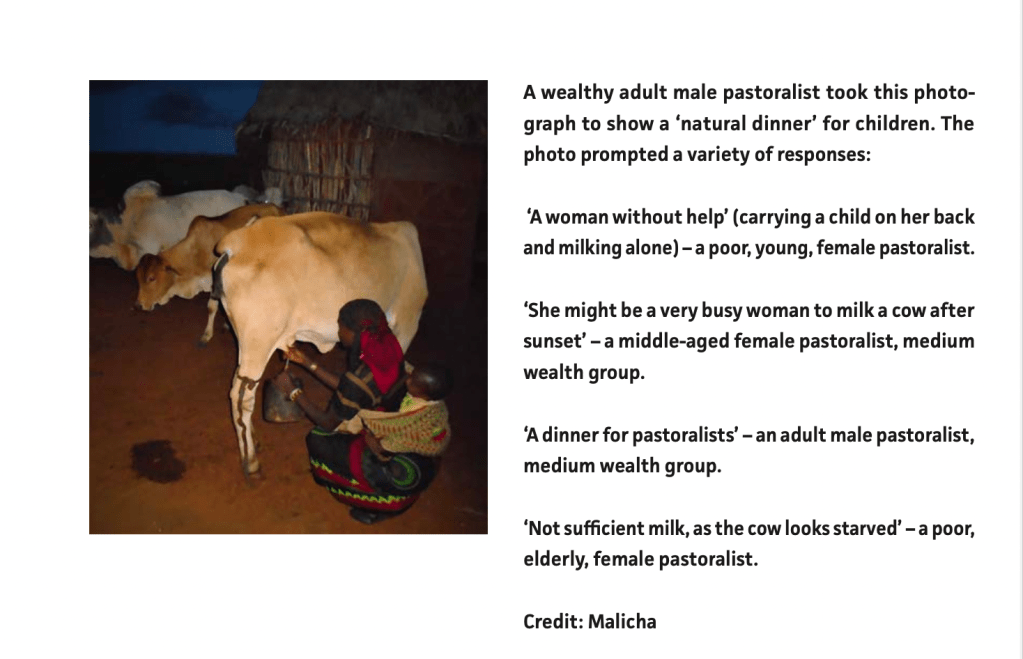

For example, enter the first of several rooms in our thought-experiment exhibition, “Rethinking Pastoralism Today.” On the wall there, you find pictured with a sidebar and attribution:

Source: S. Bose (2023). Photovoice With Pastoralists: A Practical Guidebook. PASTRES, Institute of Development Studies, Sussex and the European University Institute in Florence. Reproduced with permission and accessed online at https://pastres.files.wordpress.com/2023/11/photovoice-guide-digital.pdf (Photo by Malicha, used with permission of the ERC PASTRES project)

You read the side-bar again, and then see the caption given by exhibition’s curator: LIKE SO MUCH IN LIFE (YOURS INCLUDED), PASTORALISM IS NOT ONE WAY ONLY. That sticks in your mind, and you suspect those of others.

III

What makes this kind of curatorial practice such a useful entry point is that even the most radical exhibitions guided by progressive politics have to finds ways to work within the conventional “white cube” constraints of rooms, floors and walls upon which to hang rectangles or display against.

By extension, the most radical development recastings have to be in productive tension with current ways of seeing things as well.

–Take another illustration hanging on the walls of this exhibition, that of the policy cycle:

But you, like every other visitor to this exhibition, are your own curator in the sense of having to ask: What’s missing here in this representation? When it comes to actual policies, programs and project, “simplified” just doesn’t hack it. You know from experience, as do like viewers, that each stage is bedeviled by details and contingencies. Indeed, once other viewers also understand these details and contingencies, you’ve established a very effective critique of anything like a “normal cycle.”

The upshot? A viewing public that understands there is no one way to exhibit project performance. The stages hang together differently for viewers who see different details and have different criteria for whether what works or not, what fails or not. Curators who exhibit to illustrate family resemblances that are not seen by viewers as their own curators might be better thought of as exhibiting their own confirmation bias.

IV

So what?

By way of an answer, consider the following quote, seemingly unrelated and without any representation, written on a wall in the last room of this exhibition:

I propose to categorize policies according to their intended goal into a three-fold typology: (i) compensation policies aim to buffer the negative effects of technological change ex-post to cope with the danger of frictional unemployment, (ii) investment policies aim to prepare and upskill workers ex-ante to cope with structural changes at the workplace and to match the skill and task demands of new technologies, and steering policies treat technological change not simply as an exogenous market force and aim to actively steer the pace and direction of technological change by shaping employment, investment, and innovation decisions of firms.

R. Bürgisser (2023), Policy Responses to Technological Change in the Workplace, European

Commission, Seville, JRC130830 (accessed online at https://retobuergisser.com/publication/ecjrc_policy/ECJRC_policy.pdf)

By this point you’ve seen all the representations in the preceding rooms of pastoralists who are being displaced from their usual herding sites, in these cases by land encroachment, sedentarization, climate change, mining, and the like.

But the free-standing quote makes you think: What are the compensation, investment and steering policies of government, among others, to address this displacement. That is, where are the policies to: (1) compensate herders for loss of productive livelihoods, (2) upskill herders in the face of eventually losing their current employment, and (3) efforts to steer the herding economies and markets in ways that do not lose out if and where new displacement occurs?

You look around the room, and what do you see? Nothing is what you see. With the odd exception that proves the rule, no such national policies are hanging anywhere or standing in place.

That too sticks in your mind as you exit and for others as well.

V

But what comes after the critical analysis of culture? What goes beyond the endless cataloguing of the hidden structures, the invisible powers and the numerous offences we have been preoccupied with for so long? Beyond the processes of marking and making visible those who have been included and those who have been excluded? Beyond being able to point our finger at the master narratives and at the dominant cartographies of the inherited cultural order? Beyond the celebration of emergent minority group identities, or the emphatic acknowledgement of someone else’s suffering, as an achievement in and of itself?

Irit Rogoff quoted in Claire Louise Staunton (2022). The Post-Political Curator: Critical Curatorial Practice in De-Politicised Enclosures. PhD Dissertation. Royal College of Art, London (accessed on line at https://researchonline.rca.ac.uk/5278/1/06.02.23_Post-correction%20Thesis%20FULL.pdf)

In answer, what comes after are efforts to curating publics for what we–and they as their own curators–recast by way of pastoral development.

A different lens to recast pastoralist mobility: “logistical power from below”

The following are excerpts from Biao Xiang (2023), “Logistical power and logistical violence: lessons from China’s COVID experience,” Journal of Contemporary East Asia Studies (accessed online at DOI: 10.1080/24761028.2023.2285022).

Logistical power, be it from above or below, is defined in the article as the “capacity to initiate, coordinate, and stop mobility”:

A state gains infrastructural power by building roads, but does not acquire significant logistical power unless it can collect real-time traffic data, monitor all vehicles, and communicate with individual drivers on the move. More importantly, the concepts of infrastructural power and logistical power point to different analytical questions. Infrastructural power is by definition state power, and the concept is meant to explain how and why modern states, wielding much less despotic power than traditional rulers, can effectively govern societies of tremendous scale and complexity; and why the state and civil society have both become more powerful in the modern times. Infrastructural power enables modern states to govern through society instead of over society. Logistical power, in comparison, has its origin in social life. In most parts of human history, it is the marginal groups – nomads, migrants, hill tribes, petty traders, vagabonds and many others – which are most capable of exercising logistical power. The critical question associated with the concept of logistical power is not how state and society gain more power at the same time, but rather how state concentrate logistical power at the cost of people’s logistical power, in which process society becomes fragmented and loses its capacity of coordinating mobility.

Logistical power is the ability to coordinate mobility, and can be possessed by state and non-state actors. Logistical violence is state coercion through forced (im)mobility. Logistical power from below, namely citizen’s capacity to move and to form networks beyond government control, was a driving force behind economic reforms in the 1980s. By the 2010s, logistical power from above – the coordination of mobility by larger corporations and the state in particular – had become the dominant means of organizing the mobility of people, goods, money, and information.

So what?

While appearing inescapable due to its infrastructural and logistical power, the state has profound difficulty in controlling people’s thoughts, emotions, or communications. When talking to each other, citizens can construct a lifeworld of common sense, interpersonal trust, and mutual assistance. Such a lifeworld may provide a base for the capacity to refuse and resist forces like logistical violence.

State-sponsored sedentarization is logistical violence, the chief resistance to which is and remains the logistical power of pastoralists who move their herds and/or household members outside these settlements.

“Adaptable” and “flexible” are not nuanced enough to catch the place-specific nature of pastoralist improvisations

–Return to an old resource management typology. Its two dimensions are: (1) fixed resources/mobile resources and (2) fixed management/mobile management.

The repeated example of the mobile resources/mobile management cell has been pastoralist (nomadic/transhumant) herders. Fortunately, the truth of the matter has always been more usefully complicated.

From the standpoint of sustaining biodiversity across wide rangelands, some pastoralist systems are examples of mobile management (e.g., of grazers or browsers) with respect to fixed resources (different patches at different points and times along routes or itineraries). Indeed, this may be occurring because fixed on-site biodiversity management is too costly to undertake, if not altogether unimaginable otherwise.

–Now ratchet up the complexity. What had been mobile management must now be fixed; and what had been a fixed resource or asset now must be mobile.

Example: During the COVID lockdown, herders created informal bush markets at or near their kraals as alternatives to the now-restricted formal marketplaces (e.g., as reported by Ian Scoones and his colleagues). So too do formal associations of pastoralists participating in distant conference negotiations or near-by problem-solving meetings exemplify a now differently fixed resource exercising now differently-mobile management.

It’s good to remember that not only government can (and should) make their fixed-point resources–formal markets or social protection infrastructure–mobile.

—So what?

Terms, like “adaptable” and “flexible,” are not nuanced enough to catch the place-specific improvisational property of that adaptability and flexibility in undertaking shifts from fixed to mobile or mobile to fixed.

More formally, being skilled at real-time improvisation is what we also must expect of pastoralists whose chief system control variable is their real-time adjustments in grazing/browsing intensities (which can of course include adjusting livestock numbers through off-take).

Pastoralists as social figures

We consider a timeless model of a common property resource (CPR) in which N herdsmen are able to graze their cattle. The model has been constructed deliberately along orthodox economics lines. . . .We begin with a timeless world. Herdsmen are indexed by i (i = 1, 2, …, N). Cattle are private property. The grazing field is taken to be a village pasture. Its size is S. Cattle intermingle while grazing, so on average the animals consume the same amount of grass. If X is the size of the herd in the pasture, total output – of milk – is H(X, S), where H is taken to be constant returns to scale in X and S.

Dasgupta, P. (2021), The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. London: HM Treasury: 221 (internal footnotes deleted)

After such bloodless abstractions, it’s a wonder more readers don’t rush to the anthropological literature for descriptions of really-existing pastoralists and their herding practices.

The methodological problem, though, is that there’s really-existing, and then there’s really-existing. There are pastoralists interviewed and quoted. Then there’s the social figure of the pastoralist, a composite assembled by a researcher to represent the typical features of the pastoralists that have been studied.

All well and good, if you understand that the use of social figures extends significangtly beyond the confines of anthropology or the social sciences. Social figures “potentially have all the characteristics which would be considered character description in literary studies,” notes a cultural sociologist, adding, “unlike ideal types, for example, which are written with a clear heuristic goal in a scientific context, social figures can also appear in public debate or be described in literary texts.”

So what? “For theorizing, this means. . .attention must be paid to a good figurative description: Is the figurative description vivid, descriptive and, as a figure, internally consistent? Does it accurately reflect the social context to which it refers? Therefore, the criteria to assess quality in theorizing must be complemented by literary criteria.”

And one of those literary conventions helps explain why the social figure of the pastoralist today is frequently compared and contrasted to the social figure of the pastoralist in the past. “[T]here are often antecedent figures for a social figure. . .The current social figure can then be understood as an update of older social figures.”

A small matter, you might think, and easily chalked up to “this is the way we do historial analysis.” It is not, however, a slight issue methodologically, when comparing your pastoralist interviewees today with the social figures of pastoralists in the past ends up identifying “differences” that are more about criteria for rather than empirics in “really-existing.”

Source. T. Schlechtriemen (2023). “Social figures as elements of sociological theorizing.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory (accessed online at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1600910X.2023.2281233)

Source. T. Schlechtriemen (2023). “Social figures as elements of sociological theorizing.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory (accessed online at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1600910X.2023.2281233)

viewed from the paradigm of repair (newly added)

“What if the rise of China,” [Jerry] Zee poignantly asks, “were to be approached literally, through the rise of China into the air?” Amidst official and popular accounts of China’s authoritarian ruling, Zee’s Continent in Dust is a striking example of how to write about China and Chinese politics otherwise. The book focuses on how weather events—specifically, those involving dust, aerosols, and particulate matter—are sites for political breakdown and emergence, revealing that the Chinese political system is anything but static.

Zee opens the book with a story of a resettled ex-herder family, whose herds have allegedly overgrazed pastures in inner Mongolia. This, in turn, has resulted in the spread of dust storms, or “wind-sand” (feng sha 风沙).2 Controlling the dust flow has become a state priority, and so these ex-herders have adapted: having left behind their old jobs, they now drive civil servants across fragile dunes, airdrop seeds, and stabilize sand. These state-contracted environmental engineering jobs, however, are only “semipredictable,” leaving the ex-herders caught in “a state of constantly frustrated anticipation.”

Still, how does this offer new insight into China at large? Because, by following the dust, Zee reveals that the plight of these ex-herders is not because of the popularly accepted idea of “a neoliberalization of the socialist state.” Instead, the wind-sand shows how bureaucrats view ex-herders as both a source of “social instability” in rural frontiers and as an on-demand workforce that can furnish state sand-control programs. In other words, ex-herders represent China’s “experiment in governing,” swept in an atmosphere of “windfall opportunities for work and cash,” a departure from the declining pastoral economy. This story is not about the rise of neoliberal China but, instead, the “delicately maintained condition of quietude” deemed harmonious and stable enough for the Chinese state.3

https://www.publicbooks.org/protean-environment-and-political-possibilities/

Hands-on work is necessary to cultivate the awareness that architecture cannot be contained within the plot of land.

The way I came to this awareness was cleaning the facades of buildings with my own two hands. This work constitutes the ongoing series The Ethics of Dust, which I began in 2008. These artworks emerged from the intersection of architecture and experimental preservation. I wanted to preserve the dust that would normally be thrown out, because it seemed to me, intuitively at first, that this dust contained important information about architecture’s environmental footprint. This dust, which you can see deposited as dark stains on facades, comes in large measure from the boilers of buildings, as well as electric power plants and traffic. The smoke produced as a byproduct when we heat, cool, and electrify buildings is as much a condition of possibility for architecture as concrete or steel. The airborne particles we call smoke or dust are therefore an architectural material. Yet smoke cannot be contained inside the plot of land. To manipulate this material requires new ways of caring for architecture that encompass this larger territory. It invites us to imagine how to care for the atmosphere as an airborne built environment.

https://placesjournal.org/article/repairing-architecture-schools/

What if the built environments of the many different pastoralists include all manner of dust from herding livestock, cooking in the compound, transport speeding down dirt roads, this year’s droughts. intermittent sand storms, and the sudden dust-devils? What if architectural schools are moving from a pedagogy of new construction (think: development) to repair and renovation of the already built? What do these new generations of faculty and students offer by way of advice to really-existing pastoralists today?

One answer from the last citation: “It is important, also, to listen and learn from communities who inhabit the buildings and environments that need repair, because they know best what is broken.” To put it another way, only in a some versions of particulate matter is dust broken.

2 thoughts on “Fresh perspectives on livestock herders, rangelands, drought, pastoralist improvisations, mobility and more (newly added last entry)”