How can one company be worth more than the world’s third largest economy.. . .The financials of the AI boom are so enormous as to defy comprehension.

Well one thing that is not miind-bobbling: AI will have its own answers for this.

How can one company be worth more than the world’s third largest economy.. . .The financials of the AI boom are so enormous as to defy comprehension.

Well one thing that is not miind-bobbling: AI will have its own answers for this.

This photograph shows what were formerly residential lots now abandoned and empty in a part of Detroit, Michigan:

According to a major expert, these instances require us “to think about innovative and productive ways to manage and transform vacancy for long-term sustainability” not only in Detroit but in like now peri-urban areas (Dr. Toni Griffin, Professor in the Practice of Urban Planning at the Harvard Graduate School of Design commenting on the presentation, “Last House on the Block: Black Homeowners, White Homesteaders, and Failed Gentrification in Detroit,” accessed online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umqU1xj5yPA).

I agree and take this opportunity to recast what you see in that picture in equally policy relevant ways for low-density grasslands in parts of Africa.

I

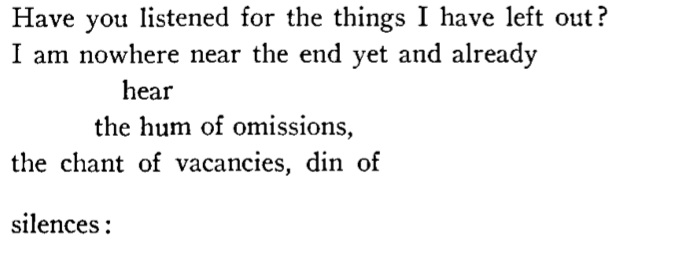

The poet, A.R. Ammons, also talks about the empty lot (TCP1, 28) and vacant land (TCP1, 49), and vacancy for him can indeed be complete emptiness (TCP2, 277). But many other times, vacancy is–as empty lots and vacant land–a bounded set full of properties (in multiple senses of that word). Here is an extract from his poem, Unsaid:

. . . . . .

To revert to social science terms, those gathered “boundaried vacancies” are both inlined and outlined. The above photo outlines only what we see at that time. What’s missing are the multiple inlined versions: not just the biophysical activities out of sight at that time and place, but the dense socio-economic relations that crisscross the space and the times we don’t see.

For all I know, there could be tents there at another time of year; or a craft and arts fair; or new construction to start the day after. Property is still being held, memories have been recorded; invisible expectations remain active for and about the photographed. The painter Gérard Fromanger noted that a blank canvas is ‘‘black with everything every painter has painted before me.” So too is the photo far more dense and opaque than what you see or can see.

II

So what? Just what does this mean for “the management of vacancy,” be it in peri-urban Detroit or the low-density rangelands of East or Southern Africa?

It means we have to think more densely, more granularly, than photographic reality could ever permit.

For example, what if the former settler ranches now subject to the mixed (arable, horticultural, animal) uses found in contemporary East and Southern Africa are in fact the result of that having “to think about innovative and productive ways to manage and transform vacancy for longer-term sustainability”?

In Detroit, we see by and large white urban farmers moving into these depopulated neighborhoods. In Africa examples, the racial demographics are largely reversed, but the analogy remains its strongest: Just as this urban farming has been mistakenly criticized as failed gentrification (the first wave of Detroit urban farmers never saw themselves as gentrifiers), so too arable and agro-pastoral farmers are mistakenly criticized for falling short of a livestock ranching thought to be more suitable by governments and their experts. Yet what to do with the finding that neither gentrification nor ranching, as ideal types, were ever part of the mixed-use practices on the ground?

More important (at least for me) the policy implications differ depending on the benchmark against which to assess really-existing variety on the ground. Is it any wonder that “gentrification”, like “dryland livestock ranching”, have no agreed-upon definitions? (Academics are still debating the causes and consequences of gentrification here in the US.) Is it any wonder then that both concepts are never so fiercely argued over as when they’re offered up as “solutions”?

But still: What to do? Here I think Ammons nails our collective starting point: It’s only that what is missing cannot be missed if spoken out.

Source

Ammons, A.R. (2017). The Complete Poems of A.R. Ammons, Volume 1 1955 – 1977 and Volume 2 1978 – 2005. Edited by Robert M. West with an Introduction by Helen Vendler. W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY. (The poem, Unsaid, can be found in TCP1, 54 – 55.)

For more Ammons, see Major Read: Ammons and regulation

The proposition I write to support is: “When having less knowledge is key to knowing more.” I want to demonstrate how tomorrow we might get all manner of official regulations right—when today we rethink “regulation” as a category of knowledge. In arguing so, I appeal to the poetry of A.R. Ammons.

Ammons, a great American poet of the last half of the 20th century, was tenacious in returning again and again to a set of topics he felt he hadn’t gotten quite right. One of the subjects was how knowing less entails “knowing” more. It’s his analytic sensibility in persistent revisiting a topic from tangents affording different insight and nuance that I rely on as an optic to parse my own topic of government regulation.

Policy types typically fasten to knowledge as a Good Thing in the sense that, on net, more information is better in a world where information is power. Over an array of accounts—and his tenacity meant he wrote a great deal—Ammons insists that the less information I have, the better off I am—not all the time, but when so, then importantly so. (To be clear and telegraph ahead, he is not talking about “ignorance is bliss.”)

For those working in policy and management—and I include myself—how could “the less we know, the more we gain” be the case and what would that mean when it comes to the heavy machinery called official regulation? Is there something here about the value of foregrounding inexperience—having less “knowledge”—as a way of adding purchase to rethinking difficult issues, in this case, regulation?

***

Start by dispensing with popular meanings of “the less I know, the more I know.” It is easily reversed to “the more I know, the less I really know.” This is the conventional wisdom that “data and information” are not knowledge—in fact the opposite. I also do not pursue another sense of “the less I know, the more I know” that Ammons foregrounds from time to time: the hiving off what we thought we knew creates the stuff from which new knowledge is formed. It is my failing—not Ammons’s—that I cannot see how “from-ruins-and-waste-come-something-altogether-better” applies to the 70,000+ paged IRS code and other volumes of government regulations.

My focus instead is on a very difficult set of insights in some of his poems. Let’s jump into the hard part—Ammons’s poem, “Offset,” in its entirety:

Losing information he

rose gaining

view

till at total

loss gain was

extreme:

extreme & invisible:

the eye

seeing nothing

lost its

separation:

self-song

(that is a mere motion)

fanned out

into failing swirls

slowed &

became continuum.

(TCP1, 418)

Please reread the poem once more.

Part of what Ammons seems to be saying is that by losing information—the bits and pieces that make up “you”—you gain by becoming whole and continuous. As it were, “loss gain” becomes a single term. You cease to be separate, your bits and pieces slow down, fan out, spread into a vital one. We empty our minds so as to attend to what matters—emptying the eye to have the I. An obvious example others have noted: If obsessive thoughts, compulsive behaviors, and restraining inhibitions are, in their own ways, altogether absorbing forms of self-knowledge, then this is knowledge we need not to know in order to have more to know better.

How, though, is this different from ignorance is bliss or, less pejoratively, seeking to know only what you need to know? Part of Ammons’s answer appears to be getting to the point where you know enough to be naïve again, to be open to the wonder of it all, to give yourself up to the kind of attention that is, if you will, self-reabsorbing. To telegraph ahead once again, naïveté does not center around knowing and not-knowing for Ammons: There’s feeling and living, wishing and dreaming, desire and more, and such are different kinds of “knowing,” as if thinking feels and feeling thinks.

Naïveté here is the adult version of child-like, decidedly not the childish that gutters out early. It is positive, because adult wonder and curiosity are the space for noticing and being alert to more—an orientation that gains from the loss of information. Compare this, however, to what is expected of government regulators: Whatever happens, they must not be uninformed or naïve—in a word, inexperienced—and when they are, shame on them.

The ways in which this wonder and inexperience do matter for regulation means staying with Ammons a bit longer. For him, staying uninformed and open to new experiences is the hard work of an affirming study:

….my empty-headed

contemplation is still where the ideas of permanence

and transience fuse in a single body, ice, for example,

or a leaf: green pushes white up the slope: a maple

leaf gets the wobbles in a light wind and comes loose

half-ready: where what has always happened and what

has never happened before seem for an instant reconciled:

that takes up most of my time and keeps me uninformed:

(TCP1, 497-498)

Being empty-headed is part of knowing enough: having to know less so as to be ready for whatever the next experience you proved to have been half-ready for in hindsight. It’s as if Ammons is asking us to be smart enough to see it’s more than about a knowing doubt and a knowing certainty.

Living is the space for feeling, which is where “knowing,” writ large, belongs: “how can I know I/am not/trying to know my way into feeling/as//feeling/tries to feel its way into knowing,” he asks in “Pray Without Ceasing” (TCP1, 779). This notion of a half-readiness open to new experience and the wonder awaiting is nicely caught in the ending lines of one of my favorites, “Cascadilla Falls”:

Oh

I do

not know where I am going

that I can live my life

by this single creek.

(TCP1, 426)

By the time you surge to those lines, there is so much feeling in that “Oh” you might miss how living takes place beyond not-knowing.” Or better, the line break of “do/not know” intimates that the doing of “not know” is a good part of living that life.

***

Regulation from this viewpoint is never a case of regulators starting with knowledge and assuming what matters for living resides elsewhere. Regulation isn’t about expunging naïveté as inexperience but—in ways not yet clear—cultivating it. What is clear is the starting point, however: Wonder is not dread; naïveté is not ignorance; and no-longer-knowing is not not-knowing.

In this way, Ammons makes a frontal attack on what policy types hold very dear: the notion of usefulness. In his essay, “A poem is a walk,” Ammons defers to a paradox: “Only uselessness is empty enough for the presence of so many uses”. Only uselessness is a sufficiently capacious category to embrace all the uses that come and go with experience and ensuring space for more feeling and living.

What could better capture all the many uses as they shift to the wayside than uselessness, “an emptiness/that is plenitude” (TCP1, 503)? Less and less information, against this backdrop, empties us and thereby makes us—leaves us open—differently. It is, in Ammons’s wonderful turn of phrase, to be “emptied full” (TCP2, 4). To seek more and more knowledge and information and never waste what has already been gotten leads to in Ammons’s acid throwaway, “total comprehension is/a wipe-out” (TCP1, 659). It’s a wipe-out because this totality leaves no room for more.

Where, then, does this leave us when it comes to “knowing” regulation better?

***

In answer, I ended up going back to Ammons’s “The Eternal City”—“After the explosion or cataclysm, that big/display that does its work but then fails/out with destructions, one is left with the//pieces. . .” (TCP1, 596). These lines resonate with what I had read in one of Rainer Maria Rilke’s letters. He is writing about the sculpture studio of Auguste Rodin:

It is indescribable. Acres of fragments lie there, one beside the other. Nudes the size of my hand and no bigger, but only bits, scarcely one of them whole: often only a piece of arm, a piece of leg just as they go together, and the portion of the body which belongs to them. Here the torso of one figure with the head of another stuck onto it, with the arm of a third. . .as though an unspeakable storm, an unparalleled cataclysm had passed over this work. And yet the closer you look the deeper you feel that it would all be less complete if the separate bodies were complete. Each of these fragments is of such a peculiarly striking unit, so possible by itself, so little in need of completion, that you forget that they are only parts and often parts of different bodies which cling so passionately to one another.

I read the passage—at least one other translation captures the same sense—as suggesting that Rodin’s “cataclysm” incorporated fragments that were, in a sense that matters for our purpose, more complete as separate fragments. So too Ammons’s “cataclysm” in “The Eternal City” refers to pieces that are themselves whole—asynoptic, unassimilable, piece next to piece. Another of Ammons’s lines, “all the way to a finished Fragment,” catches the sense I am after here (TCP1, 366).

By extension, we’d have to believe that official regulations ad seriatim, while appearing a growing shambles, are in fact more complete as the piece-work of individual regulations than they would be were they improvised into something new or part of, in policy-speak, a more integrated body of regulations for use over time.

How could this be?

***

One way ahead, Ammons implies, is to see how the waste of regulation isn’t decline-and-fall, but rather the rearguard action against such declension narratives: an argument for creating room for us to recast decline. Ammons directs our attention, for example, to waste-as-generosity in “The City Limits,”

. . . .when you consider

the abundance of such resource as illuminates the glow-blue

bodies and gold-skeined wings of flies swarming the dumped

guts of a natural slaughter or the coil of shit and in no

way winces from its storms of generosity; when you consider

that air or vacuum, snow or shale, squid or wolf, rose or lichen,

each is accepted into as much light as it will take, then

the heart moves roomier. . .

(TCP1, 498)

The “heart moves roomier” not because the pile is any less shite, but because it opens to being more—certainly more than that mortal coil. This is the hot mess of feeling and living expansively, of being somatically sprawled all over the place, now. Regulatory waste in this mode is a spectacularly, can’t-keep-our-eyes-off-it sight/site to behold, maverick and inciting at the same time.

The hot mess that you can’t keep your eyes—our inner and physical I’s—off and the incitements it offers take us to Ammons’s late, long poem, Garbage (TCP2, 220-306). (Famously, Garbage, for which Ammons won the 1993 National Book Award for Poetry, was inspired by his passing an immense heap of garbage alongside the Florida Interstate.) Mountains and mountains of garbage are “monstrous”; in fact

… a monstrous surrounding of

gathering—the putrid, the castoff, the used,

the mucked up—all arriving for final assessment,

for the toting up in tonnage, the separations

of wet and dry, returnable, and gone for good:

(TCP2, 234)

For Ammons “gone for good” is decidedly ambiguous, begging the question about just to what good has garbage gone for. An answer—and Ammons resists being pinned down to any one answer—lies in the garbage that human beings themselves are:

we’re trash, plenty wondrous: should I want

to say in what the wonder consists: it is a tiny

wriggle of light in the mind that says, “go on”:

(TCP2, 245)

Nothing integrated about this! For: “Go on” to what, in a world where garbage and waste conjure a meaninglessness of things and of our own existence, as we too are trash? In the case of Ammons, the garbage we are and the meaninglessness that poses, like capacious uselessness, offer up the wonder of being more—of meaning possibly—once we leave space for such feelings and experience:

we should be pretty happy with the possibilities

and limits we can play through emergences free

of complexes of the Big Meaning, but is there

really any meaninglessness, isn’t meaninglessness

a funny category, meaninglessness missing

meaning, vacancy still empty, not any sort of

disordering, or miscasting or fraudulence of

irrealities’s shows, just a place not meaning

yet—…

…..

…there is truly only meaning,

only meaning, meanings, so many meanings,

meaninglessness becomes what to make of so many

meanings:…

(TCP2, 277)

That word, “becomes”—that insistence on meaning-less possibility as a “funny category”—is, we see by way of conclusion, core to having room to recast regulation.

***

Richard Howard, himself no mean commentator on Ammons’s poetry, points the way: “How often we need to be assured of what we know in the old ways of knowing—how seldom we can afford to venture beyond the pale into that chromatic fantasy where, as Rilke said (in 1908), ‘begins the revision of categories, where something past comes again, as though out of the future; something formerly accomplished as something to be completed’”.

The importance of this revising categories of thinking and living is captured in an interchange Ammons had with Zofia Burr. When pressed by Burr, he summed up: “I’m always feeling, whatever I’m saying, that I don’t really believe it, and that maybe in the next sentence I’ll get it right, but I never do”.

Imagine policymakers and regulators, when pressed, recognizing that not getting it right today places them at the start of tomorrow’s policymaking—not its end but its revision as “policymaking” and “regulation.” For that to happen, they’d have to understand just how funny-odd a category regulation is.

Ammons, if I understand him, is insisting that in the compulsionto “get it right the next time around,” there at least be a next time (room) to make it—this revision of categories—better. Ensuring (risking) there is a next time is the way we keep open to—empty for—the feeling and living and participating that, in the process, push conventional notions of regulation to the periphery, changing their milieux, rendering regulation less and less meaningful and thus returning it as a concept and instrument to us re-freshed and re-wondered about; in short: recasted.

Again, how so? Let’s jump into Ammons’s deep-end one last time:

Yield to the tantalizing mechanism:

fall, trusting and centered as a

drive, falling into the poem:

line by line pile entailments on,

arrive willfully in the deepest

fix: then, the thing is done, turn

round in the mazy terror and

question, outsmart the mechanism:

find the glide over-reaching or

dismissing—halter it into

a going concern so the wing

muscles at the neck’s base work

urgency’s compression and

openness breaks out lofting

you beyond all binds and terminals.

(TCP1, 535)

(You may want to re-read the poem one more time. I return to that “deepest//fix” momentarily.)

Ammons commented on this poem, “The Swan Ritual”: “The invention of a poem frequently is how to find a way to resolve the complications that you’ve gotten yourself into. I have a little poem about this that says that the poem begins as life does, takes on complications as novels do, and at some point, stops. Something has to be invented before you can work your way out of it, and that’s what happens at the very center of a poem”.

Ammons touches on the major implication extended here: If rendering any regulation useless takes us closer to reinventing what “regulation” is, so too reinventing “regulation” can render an existing regulation useless. Regulating to reduce risk and inequality or improve economic growth and statecraft is that way we rethink these ends so to make those other means or ends no longer useful.

To rethink (revise, redescribe, rescript, recast, refashion, recalibrate) the categories of knowing and not-knowing is to resituate—make room for—the cognitive limits of “knowing” that matter. (Think by way of different examples pastiche in visual art or remixing in dub reggae.) This is to renew, as in re-render, re-know and re-understand. The eye is no longer fixed on where it had settled before, but with a new focal point in sight (this being today’s version of our wager on redemption). That, truly, is the fix we want to be in, “the deepest//fix.” It is where wonder renders dread incomplete, where knowledge is unlearned, where knowledgeable gives way to refreshened inexperience, and, in Ammons’s astonishing lines, “where what has always happened and what/has never happened before seem for an instant reconciled”.

Principal sources:

Ammons, A.R. (1996). Set In Motion: Essays, Interviews, & Dialogues. Ed. Zofia Burr, The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI.

—————— (2017). The Complete Poems of A.R. Ammons, Volume 1 1955 – 1977 and Volume 2 1978 – 2005. Edited by Robert M. West with an Introduction by Helen Vendler. W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY. [The volumes are referred to in the blog entry as TCP1 and TCP2, respectively.]

Howard, R. (1980). Alone With America: Essays on the Art of Poetry in the United States Since 1950. Atheneum: New York, NY. Rilke, R.M. (1988). Selected Letters 1902-1926. Transl. R.F.C. Hull, Quartet Encounters, Quartet Books: London.

Rilke, R.M. (1988). Selected Letters 1902-1926. Transl. R.F.C. Hull, Quartet Encounters, Quartet Books: London.

This article has challenged the conventional wisdom on labor markets, advancing the following propositions: (1) There is no such thing as a labor market that is not socially and politically constructed. (2) All real-world labor markets reflect specific balances of power. (3) The balances of power reflect not only the abundance or scarcity of market (exit) opportunities but a wide range of political and social factors. (4) Therefore, laws and regulations to shift those balances do not constitute “interventions” into free markets. (5) Such laws and regulations are not necessarily inefficient or undesirable, and they do not require a particular justification based on market failures.

Steven K. Vogel (2025). “Toward an Interdisciplinary Political Economy of Wages.” Politics & Society: 1 -20 (accessed online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00323292251387041; my bold)

Economics assumes substitutability, where goods and services have alternatives in the marketplace; infrastructure reliability assumes practices for ensuring nonfungibility, where nothing can substitute for the high reliability of critical infrastructures. Without the latter, there would be no markets for goods and services, right now when selecting among those alternative goods and services. There is a point at which high reliability and trade-offs are immiscible, like trying to mix oil and water.

One way of thinking about the nonfungibility of infrastructure reliability is that it’s irrecuperable economically in real time. The safe and continuous provision of a critical service, even during (specially during) turbulent times, cannot be cashed out in dollars and cents and be paid to you instead of the service. It’s the service that is needed and real time, from this perspective, is an impassable obstacle to cashing out.

Which is to say, if you were to enter the market and arbitrage a price for high reliability of critical infrastructures, the market transactions would be such you’d never be sure you’re getting what you thought you were buying. Economics is more often stated only so; high reliability more often demonstrated, or not.

I

Malena López Bremme and Salvador Santino Regilme present a fabulous case study of the Syrian refugee crisis in their “Climate Change, Ecocide, and the Rise of Environmental Refugees: The Case of Syria” (2025, Political Studies, accessed online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00323217251382404?utm_source=researchgate).

Starting on article’s page 8, their case study is detailed, wide-ranging and, as far as I can determined, conclusive:

This case study identifies Syria’s prolonged dictatorship as a period characterized by ecological risks and mismanagement, culminating in protracted war and forced displacement. It explores the climate-conflict hypothesis related to environmental migration, interconnected through a complex chain of water scarcity, drought, governmental neglect, agricultural failure, socioeconomic decline, political oppression, rural-urban competition, internal displacement, civil unrest, and the involvement of regional and global actors. (my bold)

where the hypothesis in question was:

Rather than treating environmental stress as a direct trigger of violence, [the article] theorizes vulnerability as co-produced— arising from the interaction of climate-induced degradation, authoritarian governance, institutional neglect, and deep-rooted socioeconomic inequalities. In the Syrian case, prolonged drought was not a singular cause but one element in a relational and contingent configuration of crisis. Syria thus exemplifies how environmental stress becomes politically explosive under specific governance failures and international conditions. (terms highlighted in the article)

Co-produced, relational and contingent indeed make for complex networks of causality. I strongly encourage the reader interested in the topic of climate refugees to read pp. 8 – 16 of this article.

What I find questionable is the chief policy implication: “the necessity for global governance to address the ecological and humanitarian impacts of climate-induced conflicts.”

II

One can well agree with the authors that the case illustrates what can happen with “sovereign abandonment—a mode of power where state inaction or deliberate neglect leads to death and displacement.” But, even where true, the chief policy implication isn’t then: global governance is required. Rather, the immediate implication is: Don’t abandon sovereignty elsewhere if only because the Syrian case study establishes a counterfactual demonstrably worse.

But the necessity of protecting positive forms of national sovereignty–humane, non-ecocidal–is not, I think, what the authors are recommending.

So what? One would be hard-pressed to say that novels–which when they work are their own form of case studies–argue for global governance. Or more positively, perhaps the latter is now the function of science fiction and the increasing calls to incorporate speculative fiction into policy formulation.

Maintenance and repair take center-stage: 1

Maintenance and repair take center-stage: 2

Maintenance and repair take center-stage: 3

I

Proposition. M&R (maintenance and repair) signals an already-established state/stage of infrastructure operations for which there are official and unofficial procedures, routines and protocols.

In this way, M&R provides an officially-recognized period for and expectations about identifying and updating what are or could be precursors to system disruption and failure and their prevention/avoidance strategies. Recurrent M&R is all about continuous building in of precursor resilience (e.g., using M&R for identifying obsolescent and now possibly hazardous software or other components).

II

Implications. Start at the macro-level but with more granularity. A form of societal regulation occurs when critical infrastructures, like those for energy and water, prioritize systemwide reliability and safety as social values, at least in real time. These values are further differentiated and uniquely so within infrastructures.

Consider the commonplace that regulatory compliance is “the baseline for risk mitigation in infrastructures.” There is no reason to assume that compliance is the same baseline for, inter alios, the infrastructure’s operators on the ground, including the eyes-and-ears field staff; the infrastructure’s headquarters’ compliance staff responsible for monitoring industry practices in order to meet government mandates; the senior officials in the infrastructure who see the need for more and better enterprise risk management; and, last but never least, the infrastructure’s reliability professionals—its real-time control room operators, should they exist, and immediate support staff— in the middle of all this in their role of surmounting any stickiness by way of official procedures and protocols undermining real-time system reliability.

To put it another way, where reliable infrastructures matter to a society, it must be expected that the social values reflected through these infrastructures differ by staff and their duties/responsibilities (e.g., responsibilities of control room operators necessarily go beyond their official duties). This also holds for the operational stage, “maintenance and repair.”

III

So what?

M&R is best seen as providing increased precursor resilience, which is best seen now as a differentiated process–resilience will look very different from the intra-infrastructural perspectives of enterprise risk management and real-time control room operations–and which takes place within a wider framework of social regulation not associated solely with the official infrastructure regulator of record.

Note that infrastructures do convey and instantiate social values, but these values—particularly for systemwide reliability and safety—are not the command and control of “infrastructure power”. In the latter, formal design is the starting point for eventual operations; in the latter actual operations are the informal starting point for real-time redesign. Not only do actual implementation and operations fall short of initial designs, one major function of operations is to redesign in real time what are the inevitably incomplete or defective technologies of infrastructure designers and defective regulations of the regulator of record.

In this way, it’s better to see “maintenance and repair” as part and parcel of normal operations that necessarily follow from and modify formal infrastructure design. M&R’s focus on improving precursor resilience becomes one primary way of maintaining the infrastructure’s process reliability when older forms of high reliability are no longer to be achieved because of inter-infrastructural dependencies and vulnerabilities.

I

One irony of infrastructure analysis is the finding that they and their continuous supply of services are saturated with contingencies, not least of which are task environment shocks and surprises.

First, the fact that infrastructures involve on-the-ground assets has long been recognized as rendering them vulnerable to all manner of wider environmental contingencies:

Once developed, these infrastructural assets are difficult to relocate or repurpose. In effect, capital investments become affixed to specific built environments and localities, forming stable networks of spatial interdependence. These networks, on the one hand, facilitate circulation and accumulation by linking resource frontiers, but on the other, also expose capital to territorial and political contingencies inherent in fixed spatial arrangements. . .

(accessed online at https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21622671.2025.2569670)

The same applies to the start of infrastructure development with the lag between investing in new infrastructures and their starting construction:

. . .investments were by their very nature ‘fixed’ at a certain point in time, introducing another source of uncertainty: when money was converted into physical means of production, it took an extended period of time before it began to deliver returns, but it was hard to predict all the changes that could occur while the investor was waiting to realise them.

(accessed online at https://newleftreview.org/?pc=1711, p. 29

That extended period of time includes those much-recorded shocks and surprises that explain those familiar gaps between infrastructure plan and implementation and between implementation and actual operations of what are in practice and on the ground, interconnected critical infrastructures.

It is in this context of unpredictability and contingency that we must understand the role of “infrastructure maintenance and repair”–as actually undertaken during really-existing infrastructure operations. M&R is, if you will, the best proof we have about whether or not infrastructure operations survive the unholy trinity of: the solutionism of designers and planners; “advanced” technologies introduced prematurely only to become obsolete earlier than expected; and our intensified dependence on the resulting kluge and amalgam for actual (interconnected) services in real time and over time.

II

So what? We now have a different answer to why people seek first to restore the infrastructures they have, even when as bad as they have been.

For example, why doesn’t the persisting prospect of catastrophic failures with catastrophic consequences of a magnitude 9 earthquake in Oregon and Washington State convince the populations concerned that the economic system that puts them in such a position must be changed before the worst happens? Answer: Because critical service restoration–from the Latin restaurare, to repair, re-establish, or rebuild–is the real-time priority for immediate response after a catastrophe.

Yes, let’s talk about replacing or repurposing the infrastructures we have before any catastrophe; yes, let’s talk about alternative systems with entirely different demands for maintenance and repair. But never forget that, when that catastrophe hits, the priority is to get back to where we were before the disaster, if only to repair what we what we are familiar with and know how to maintain thereafter.

“Therefore, infrastructure and connectivity, rather than trade and investment, should be the focus in order to understand the specific character of any Chinese sphere of influence among the Mekong states.” (Greg Raymond 2021. Jagged Sphere: China’s Quest for Instructure and Influence in Mainland Southeast Asia. Lowy Institute: Sidney Australia accessed online at https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/RAYMOND%20China%20Infrastructure%20Sphere%20of%20Influence%20COMPLETE%20PDF.pdf)

“What is the first act that creates the economy? It is neither production nor exchange (market or otherwise). It is the storing of wealth over time, with which I associate with investment.” (Daniel Judt 2025. “Storage, Investment, and Desire: An interview with Jonathan Levy,” Journal of the History of Ideas Blog accessed online at https://www.jhiblog.org/2025/02/24/storage-investment-and-desire-an-interview-with-jonathan-levy/)

I

Greg Raymond makes a convincing case for his point above and I too am among many who emphasize the centrality of infrastructures and their interconnectivities in underwriting economies and the maintenance of market transactions.

The point of this blog entry, however, starts with the argument of economist, Jonathan Levy, in his recent The Real Economy: Contrary to conventional economics with its fulcrum of allocation and exchange, it is investment which creates economies. And it is that association to infrastructure suggested in the above phrase, “storing of wealth,” that prompts the comments below.

Thinking infrastructurally about investment highlights three under-recognized insights that are highly policy-relevant.

II

First, investments import the long run into infrastructure analysis in ways that a focus on allocation and exchange do not. These ways range from the banal–as described above, it takes time for the infrastructure to be planned, funded, implemented and then operated as constructed and managed. But there are more invisible considerations at work.

The pressures to innovate technologies, in particular, mean that some infrastructure technologies (software and hardware) are rendered obsolete before the infrastructures have been fully depreciated. This brings uncertainty into investing in technology and engineering of infrastructures that are to last, say, two generations or more ahead. The long run ends up meaning another short-run, and those short-runs can look like boom and busts, well short of anything like “infrastructure full capacity.”

And yet, second, there are examples of infrastructures being operated beyond their depreciation cycles. Patches, workarounds and fixes keep the infrastructure in operation, even if that this reliability is achieved at less than always-full capacity. It takes professionals inside the infrastructure to operationally redesign technologies (and defective regulations) so as to maintain critical service provision reliably during the turbulent periods of exogenous and endogenous change. This includes the very diverse panoply of what is termed, unscheduled maintenance and repair.

Third, this professional ability to operationally redesign systems and technologies on the fly and in real time in effect extends what would otherwise be a shortened longer run (e.g., due to always-on innovation)–and one which is extended under the mandate of having to maintain systemwide infrastructure reliability. Introduction of what are premature innovations is countervailed by those professional patches, workaround and fixes that sustain system reliability, at least for the present. These practices are often rendered invisible under the catch-all, “infrastructure maintenance and repair,” where even operations become part and parcel of corrective maintenance. (Indeed, “short-run,” “adaptable” and “flexible” are frequently not granular enough to catch the place-and-time specific–that is, often improvisational–properties of actually-existing maintenance and repair under real-time urgencies.)

The latter means, however–and this is the key point–that maintenance and repair are far from being worthy only of an aside. Really-existing maintenance and repair and their personnel are in fact the core investment strategy for longer term reliable operations of infrastructures faced with uncertainties from the outside (e.g., those external shocks and surprises over the infrastructure’s lifecycle) and from the inside (e.g., those premature engineering innovations).

III

So what?

Since the 2007/2008 financial crisis, we’ve heard and read a great deal about the need for what are called macroprudential policies to ensure interconnected economic stability in the face of globalized challenges, ranging from defective international banking to the climate emergency. These calls have resulted in, e.g., massive QE (quantitative easing) injections by respective central banks and massive new infrastructure construction initiatives by the likes of the EU, the PRC, and the US.

What we haven’t seen are comparable increases in the operational maintenance and repair of critical infrastructures for functioning economies and supply chains, let alone for economic stability. Nor have you seen in the subsequent investments in science, technology and engineering anything like the comparable creation and funding of national academies for the high reliability management of those backbone critical infrastructures. Few if any are imagining national and international institutes, whose new funding would not be primarily directed to innovation as if it were basic science, but rather to applied research and practices for enhanced maintenance and repair, innovation prototyping, and proof for scaling up. (Please also see the call and details to establish and fund a National Academy of Reliable Infrastructure Management.)

If I am right in thinking of longer-term reliability of backbone infrastructures as the resilience of an economy that is undergoing shocks and surprises, then infrastructure maintenance and repair–and their innovations–move center-stage in ways not yet appreciated by politicians, policymakers and the private sector.

“Therefore, infrastructure and connectivity, rather than trade and investment, should be the focus in order to understand the specific character of any Chinese sphere of influence among the Mekong states.” (Greg Raymond 2021. Jagged Sphere: China’s Quest for Instructure and Influence in Mainland Southeast Asia. Lowy Institute: Sidney Australia accessed online at https://www.lowyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/RAYMOND%20China%20Infrastructure%20Sphere%20of%20Influence%20COMPLETE%20PDF.pdf)

“What is the first act that creates the economy? It is neither production nor exchange (market or otherwise). It is the storing of wealth over time, with which I associate with investment.” (Daniel Judt 2025. “Storage, Investment, and Desire: An interview with Jonathan Levy,” Journal of the History of Ideas Blog accessed online at https://www.jhiblog.org/2025/02/24/storage-investment-and-desire-an-interview-with-jonathan-levy/)

I

Greg Raymond makes a convincing case for his point above and I too am among many who emphasize the centrality of infrastructures and their interconnectivities in underwriting economies and the maintenance of market transactions.

The point of this blog entry, however, starts with the argument of economist, Jonathan Levy, in his recent The Real Economy: Contrary to conventional economics with its fulcrum of allocation and exchange, it is investment which creates economies. And it is that association to infrastructure suggested in the above phrase, “storing of wealth,” that prompts the comments below.

Thinking infrastructurally about investment highlights three under-recognized insights that are highly policy relevant.

II

First, investments import the long run into infrastructure analysis in ways that a focus on allocation and exchange do not. These ways range from the banal–it takes time for the infrastructure to be planned, funded, implemented and then operated as constructed and managed–to more invisible considerations.

The pressures to innovate technologies, in particular, means that some infrastructure technologies (software and hardware) are rendered obsolete before the infrastructures have been fully depreciated. This brings uncertainty into investing in technology and engineering of infrastructures that can last ahead, say, two generations or more. Here, the long run means another short-run, and those short-runs at times can look like boom and busts, well short of anything like “infrastructure full capacity.”

And yet, second, there are examples of infrastructures being operated beyond their depreciation cycles. Patches, workarounds and fixes keep the infrastructure in operation, even if that this reliability is achieved at less than always-full capacity. It takes professionals inside the infrastructure to operationally redesign technologies (and defective regulations) so as to maintain critical service provision reliably during the turbulent periods of exogenous and endogenous change.

Third, this professional ability to operationally redesign systems and technologies on the fly and in real time in effect extends what would otherwise be a shortened longer run (e.g., due to always-on innovation and defective design)–and extended under the mandate of having to maintain systemwide infrastructure reliability. Introduction of what are premature innovations is countervailed by those professional patches, workaround and fixes that sustain system reliability, at least for the present. These practices are often rendered invisible under the bland catch-all, “infrastructure maintenance and repair,” where even operations become part and parcel of corrective maintenance..

The latter means, however–and this is the key point of this blog entry–that maintenance and repair are far from being bland and worthy only of mention. Really-existing maintenance and repair and their personnel are in fact the core investment strategy for longer term reliable operations of infrastructures faced with uncertainties induced from the outside (e.g., those external shocks and surprises over the infrastructure’s lifecycle) and from the inside (e.g., those premature engineering innovations).

III

So what?

Since the 2007/2008 financial crisis, we’ve heard and read a great deal about the need for what are called macroprudential policies to ensure interconnected economic stability in the face of globalized challenges, ranging from defective international banking to the climate emergency. These calls have resulted in, e.g., massive QE (quantitative easing) injections by central banks and massive new infrastructure construction initiatives by the likes of the EU, the PRC, and the US.

What we haven’t seen are comparable increases in the operational maintenance and repair of critical infrastructures necessary for functioning economies and supply chains, let alone for “economic stability.” Nor have you seen in the subsequent investments in science, technology and engineering anything like the comparable creation and funding of national academies for the high reliability management of those backbone critical infrastructures. Few if any are imagining national and international institutes, whose new funding would not be primarily directed to innovation as if it were basic science, but rather to applied research and practices for enhanced maintenance and repair, innovation prototyping, and proof of scaling up.

In sum, if I am right in thinking of longer-term reliability of backbone infrastructures as the resilience of an economy that is undergoing shocks and surprises, then infrastructure maintenance and repair–and their innovations–move center-stage in ways not yet appreciated by politicians, policymakers and the private sector.

Please also see the call and details to establish and fund a National Academy of Reliable Infrastructure Management.

Engineers talk about the need for large hazardous systems to “fail gracefully.” That assumes a degree of control over technological failure as it is happening and, as far as I can tell, there is nothing “graceful” about a large technical system failing right now.

So what?

It’s not just the sheer hubris expressed in phrases like “engineering a soft landing of the economy.” It also means that even anti-utopians have been delusional at times. Karl Popper, philosopher, was known for contrasting Utopian engineering with what he called the more realistic approach of piecemeal engineering:

It is infinitely more difficult to reason about an ideal society. Social life is so complicated that few men, or none at all, could judge a blueprint for social engineering on the grand scale; whether it is practicable; whether it would result in a real improvement; what kind of suffering it may involve; and what may be the means for its realization. As opposed to this, blueprints for piecemeal engineering are comparatively simple. They are blueprints for single institutions, for health and unemployed insurance, for instance. . . If they go wrong, the damage is not very great, and a re-adjustment not very difficult. They are less risky, and for this very reason less controversial.

“If they go wrong, the damage is not very great”!? It’s the case that blueprints for piecemeal health insurance–and educational reform, government budgeting and financial deregulation, for that matter–have also been damaging. Utopian engineering is the least of our problems here.

Without the traditional physical assets that make up the foundational types of

infrastructures, such as energy networks, transport, water, waste treatment, and

communications, there is no modern economy or society.

(accessed online at https://bennettschool.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Measurement-of-social-and-cultural-infrastructure.pdf)

I

An AI-generated definition is good-enough to start: “The ‘foundational economy’ (FE) is the infrastructure of everyday life, including essential services like water, electricity, healthcare, and housing, that are required for society to function.” (The key website is The Foundational Economy.) Even at that level of abstraction, it’s clear there is no one and only FE with one and only one set of critical infrastructures in each.

More important than their numbers and diversity, it’s that “infrastructure” I take up here and expand below: Since critical infrastructures and their operating networks of personnel are required so as to make it possible for a collective to exist and thrive economically let alone societally, so too agrarian reform and the foundational economy are instrumentally linked in ways that commend further elaboration.

How so?

II

Here are ten propositions by way of answer:

1. By definition, a foundational economy would not exist if it were not for the reliable provision of electricity, water, telecoms, and transportation. Here reliability means the safe and continuous provision of the critical service in question, even during (especially during) turbulent times. This means, for example, that the physical systems as actually managed and interconnected on the ground help establish the spatial limits of the FE in question.

2. By extension, no markets for goods and services in the FE would exist without critical infrastructure reliability supporting their operations. This applies to rural landscapes as well as urban ones.

3. Other infrastructures, including reliable contract and property law, are required for the creation and support of these markets, though this too varies by context. One can, for example, argue healthcare and education are among the other infrastructural prerequisites for many FEs (as above).

4. Preventing disasters in the face existing and prospective uncertainties is what highly reliable infrastructures do. Why? Because when the electricity grid islands, the water supplies cease, and transportation grinds to a halt, then people die and the foundational economy seizes up (Martynovich et al. 2022).

5. Another way to say this is that within a foundational economy you see clearest the tensions between economic transactions and reliability management. Economics assumes substitutability, where goods and services have alternatives in the marketplace; infrastructure reliability assumes practices for ensuring nonfungibility, where nothing can substitute for the high reliability of critical infrastructures without which there would be no markets for goods and services, right now when selecting among those alternative goods and services.

6. Which is to say, if you were to enter the market and arbitrage a price for high reliability of critical infrastructures, the market transactions would be such that you can never be sure you’re getting what you thought you were buying. Much discussion around moral economies and agrarian reform can be described in such terms.

7. This in turn means there are two very different standards of “economic reliability.” The retrospective standard holds the foundational economy–or any economy for that matter–is performing reliably when there have been no major shocks or disruptions from the last time to now. The prospective standard holds the economy is reliable only until the next major shock, where collective dread of that shock is why those networks of reliability professionals try to manage to prevent or otherwise attenuate it. The fact that past droughts have harmed the foundational economy in no way implies people are not managing prospectively to prevent future consequences of drought on their respective FEs–and actually accomplishing that feat.

8. Why does the difference between the two standards matter? In practical terms, the foundational economy is prospectively only as reliable as its critical infrastructures are reliable, right now when it matters for, say, economic productivity or societal sustainability. Indeed, if the latter were equated only with recognizing and capitalizing on retrospective patterns and trends, economic policymakers and managers in the FE could never be reliable prospectively in the Anthropocene.

9. For example, the statement by two well-known economists, “Our contention, therefore, following many others, is that, despite its flaws, the best guide to what the rate of return will be in the future is what it has been in the past” (Riley and Brenner 2025) may be true as far as it goes, but it in no way offers a prospective standard of high reliability in the foundational economy (let alone other economies).

10. So what? A retrospective orientation to where the economy is today is to examine economic and financial patterns and trends since, say, the 2008 financial crisis; a prospective standard would be to ensure that–at a minimum–the 2008 financial recovery could be replicated, if not bettered, for the next global financial crisis. Could the latter be said of the FE in your city, metropolitan area or across the rural landscape of interest?

III

In short, how does your version of agrarian reform shift the odds in favor of the prospective standard for a reliable foundational economy ahead?

Note by way of concluding that the policy-relevant priority isn’t scaling up your reforms beyond the FEs as much as your determining the openness of those FEs to being modified in light of evolving affordances under reforms during the Anthropocene.

Sources.

Martynovich, M., T. Hansen, and K-J Lundquist (2022). “Can foundational economy save regions in crisis?” Journal of Economic Geography, 1–23 (https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbac027)

Riley, D. and R. Brenner (2025). “The long downturn and its political results: a reply to critics.” New Left Review 155, 25–70 (https://newleftreview.org/?pc=1711)

See also my When Complex is as Simple as it Gets: Guide for Recasting Policy and Management in the Anthropocene and A New Policy Narrative for Pastoralism? Pastoralists as Reliability Professionals and Pastoralist Systems as Infrastructure